The Education Gap nobody is talking about

With expensive tuition fees, we should be guaranteed a certain quality of education, right? Jenny Steinitz argues that this isn’t always the case.

We are often told that the collegiate system at Cambridge is one of the best things about the university: it means your educational experience is unique to you. However, the flipside of that argument is largely ignored: namely, that your ‘unique’ educational experience could be inferior to that of your peers and that there is really no way to know if this is the case.

The supervision, especially within the arts and social science subjects, is an absolutely crucial aspect to learning in Cambridge, and constitutes a large proportion of the few contact hours we receive.

However, the content and quality of these supervisions can vary widely. Supervisors differ in levels of training and levels of experience. While there is a training system in place for supervisors, the newer training systems will normally only be applied to new supervisors, rather than retraining current supervisors according to the new guidelines. Moreover, the average level of experience for supervisors can differ significantly. Some students may only ever have had PhD students as supervisors, while other students will frequently be taught by the more senior members of the department.

Directors of Studies, too, can play a large role in the quality of your education, in some cases, using their influence within the department to acquire more well-renowned supervisors for their students, and in other cases, leaving the supervisor assignments to the centralized administration system.

As a result, some students may be receiving a higher quality of supervisor and supervision throughout their time at Cambridge than others.

In summer 2014, Varsity published an article describing the complex, politicised and discrepant complaints procedures here at Cambridge. However, there is a larger underlying problem with the complaint procedure at Cambridge: how can we know when to complain in the first place?

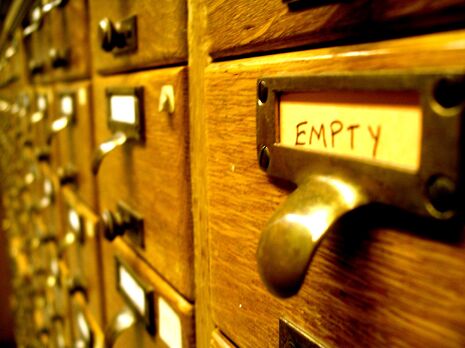

The lack of transparency involved in the administration and training of supervisors means that students have no objective way to compare their educational experiences against that of their peers, except through anecdotal evidence. As noted above, there is supposedly a minimum degree of training given to all supervisors. However, the students are not aware of what this training involves, or whether their supervisors are living up to the requirements of this training.

There have recently been steps taken to regulate the teaching time given to each student – a big step towards a fairer level of education for all students at Cambridge. The need for this is stark: a Varsity investigation last year found that contact time between colleges can vary by up to as much as 71 hours per year for the same subject.

The next logical step is to regulate the quality of that teaching time. This is not to say that all supervisions should look exactly alike, but rather that there should be publicly available guidelines provided to all students at the beginning of their course so that they may assess whether or not their supervisor is fulfilling the departmental expectations of what a supervision should look like. There should also be a clear complaints procedure at a centralised level that all students should be able to follow if they feel that the supervisions or supervisors are not fulfilling the departmental expectations set out in their supervision guidelines.

On arrival at Cambridge, many students are asked to sign a contract detailing what would be expected of them during their time at Cambridge and the consequences of not reaching those expectations. And yet, students have not been provided with the converse: what they should expect from their teaching and how to deal with unfulfilled expectations. Paying £9,000 a year for tuition, students deserve a sense of quality in their teaching.

There is then a significant gap in student educational experience. Unique doesn’t always mean uniquely good, and this is something that needs to be recognised.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025