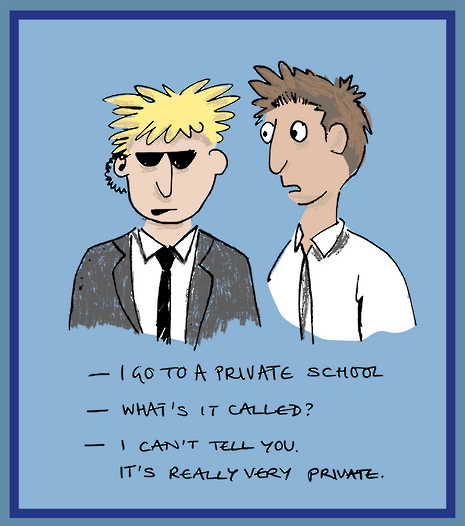

This House would abolish private education

Sam Dalton and Morwenna Jones come to blows over the legitimacy of private education

AYE: Sam Dalton

The comprehensive victory for the Nays at last year’s Union debate on the motion “This House would send its children to private school” (320 to 246) suggested that a clear majority of Cambridge students recognise the traditional, archaic nature of private education and its embodiment of elitism, hereditary privilege and sickening injustice. Strong points were made by those speaking in favour, but the broad idea of paying for better schooling, and commodifying knowledge, is not one which makes for fair education or a subsequently fair society.

A debate on grammar schools, by contrast, would most likely illicit a more tightly-contested result given that they don’t stir such passionate resentment over the influence of parental wealth or the damaging divisions that fragment society. They fit in with the dominant meritocratic ideology of modern capitalist society, allowing the brightest students to be pushed and challenged at competitive, stimulating schools that they have reached by virtue of their own talent and hard work. The fact that 33.7 per cent of all state school students admitted to Cambridge in 2012 were from grammars is evidence of their ability to produce academically excellent individuals within the public sector.

But grammar schools entail strict and unjust divisions of their own, the very reason a law was passed in the 1970s preventing new ones from being established. By deciding at the tender age of eleven whether a child should enter a grammar or comprehensive school, the most critical educational judgement of that individual’s life is being made well before anyone could be certain about their academic potential or developmental trajectory. A brutal judgement like this effectively siphons off those deemed less capable to the academic wastebin, consigning young lads to mediocrity before their voices have even broken. The message sent out is that intelligence is permanent and unchanging. That your fate is sealed and potential limited.

Such an early judgement endangers cementing these underlying social and economic inequalities rather than challenging them. Some argue by contrast that grammars give working-class children an opportunity for a first-class education that cannot be gained anywhere else, but this is only the case for the few bright poster child geniuses whose natural ability manages to shine through despite environmental disadvantages.

This is not to say that all or even most educational inequalities would vanish if private and grammar schools were dismantled, or that comprehensives offer the solutions to all current problems. Sociological research has consistently shown that the educational attainment gap between working and middle-class children increases even when they attend the same school – teachers subconsciously harbour bias in favour of students with more pronounced accents and assume they are smarter. It is depressing to note that on average only 64 students who received free school meals are admitted to each Russell Group university every year, despite 18 per cent of all students at state schools being eligible for them. This suggests that the problems are more deep-rooted and cannot be tackled through educational reform alone.

Of course we want schools to push the brightest students and assist them in reaching their potential. Of course we want top universities like Cambridge to be flooded with as many applications as possible from the academically gifted. And of course we don't want to sacrifice aspiration and high performance for an equality of mediocrity in which everybody has the opportunity to access uninspiring education. Though grammars are currently doing a better job of getting the most out of the brightest students, it is a false dichotomy to suggest that the only choices available are between highly selective schooling and excellence on the one hand, and substandard equality on the other.

In Finland all students go through nine years of common compulsory education before choosing to continue down an academic or vocational track at the age of sixteen, with excellent institutions established for this. The country consistently ranks at the top of global and European education indexes, including the UN Educational Index, managing to combine a system which promotes equality of opportunity with high levels of school autonomy, producing outstanding results in the process. The Finnish model cannot simply be plucked and installed in the UK at the click of a finger. But by at least starting to question the educational system as it exists today, and pinpointing the factors that lead to rigid inequalities and injustices, the process of reform can begin, and the building of a system that allows all to flourish can start.

NAY: Morwenna Jones

Are private schools unfair? Yes. Are they elitist? Yes. Does an ‘old boys’ network of private school alumni unjustly dominate politics, the judiciary and the media? Yes.

But, would abolishing private schools solve the problem?

In so far as there wouldn’t be any ‘private schools’ for the elite alumni to come from, then yes. But we all know it wouldn’t be long before the Range-Rover driving yummy mummies of Surrey upped sticks, moved to the catchment areas of top state schools and employed private tutors for darling Victoria or Percival. Those children originally in the catchment area, without private tutors or pushy parents, wouldn’t stand a chance. Rather than pushing for the abolition of private education, we need to improve inequalities among state schools and rethink our impression of the private sector.

Improving the inequality of state education becomes even more necessary when we consider the principal accusation put against private education: that it is downright unfair that some children are given what are perceived to be greater advantages than other children, purely because their parents were able to, and chose to, spend money on their education. To respond by saying ‘life’s unfair’ would be insensitive, but when pupils at 261 state schools registered average GCSE grades no higher than a C last summer, while their leading counterparts averaged an A*, it seems to be true. While imbalances like this exist in the state sector and directly disadvantage those who don’t send or who, perhaps more importantly, are unable to send their children to private schools, abolishing the private sector, which doesn’t contribute to the disparity in state education, is far from a priority.

Yet when we look at the inequality that private schools do promulgate, particularly academically, it is important that we refrain from indulging our media-driven estimation of these schools and their students. Looking at the private schools that boast of sending armies of eighteen year olds off to Oxbridge each year, you have every right to rail against that perceived injustice. Or you can encourage more sixth form colleges – like Hill’s Road College here in Cambridge which was recently ranked third on a Sunday Times list of schools with the highest levels of Oxbridge entry after Westminster and Eton – to try and improve and do the same.

The same can be said of facilities. Of course, at some private schools, brand spanking new laboratories, sports pitches, theatres and music centres are the norm, but, more often than not, private schools have facilities that are indistinguishable from those of high-ranking state schools. Subsequently, the same option presents itself. You can attack the schools that do have world-class facilities. Or, you can celebrate how schools (both independent and state) fortunate enough to have swanky state of the art equipment rarely miss the opportunity to benefit the wider community by making it available to the public. Better still, you can aim to improve the facilities at state-schools lower down the rankings not yet equipped with the latest computers, science equipment and sports gear, rather than abolish the schools that do have these amenities.

Nevertheless, there is one thing we must address. That, despite the success stories, Oxbridge entrants and excellent facilities state schools have to offer, the gap between state and private education continues to exist and it narrows and widens depending on where you look. This, in itself, is surely an argument for the abolition of private education.

Only it isn’t. Yes, that gap is unfair, but it is far less unfair than the wide gap in education provisions faced by children from the same economic backgrounds but who happen to live in different catchment areas and attend different schools. Abolishing private schools is futile to argue for on the basis of egalitarianism, when such disparities exist in the state sector.

It is not, however, futile to offer opportunities to the children able to benefit from a private education. That benefit may be a result of one of the scholarships that enable thousands of children from less advantaged backgrounds to attend some of the country’s most elite schools. It may be as a result of parents’ hard work and sacrifice for their child’s education. It may simply be as a result of a family’s inherited wealth. It shouldn’t matter.

Like good state schools, most good private schools specialize in offering children the opportunity to flourish, whether it’s on the stage, in the exam hall or on the sports pitch. They offer opportunities of emotional development through involvement with charities or positions of responsibility and abolishing private schools would eliminate these opportunities for everyone, apart from those lucky enough to attend top state schools where they are also on offer. Educational inequality would continue to exist regardless and to deny one child the opportunity of private education simply because another does not receive it is little better than denying UK children education completely, in order to level the playing field with the 72 million children around the world who get no education at all through no fault of their own.

We can offer some children a private education. Sometimes, that education is better than state education. The only act that would be truly unfair would be denying them the chance to take it and failing to act upon the more serious inequalities that exist among our state schools.

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026

Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026 News / Students condemn ‘insidious’ Israel trip23 January 2026

News / Students condemn ‘insidious’ Israel trip23 January 2026 Comment / Gardies and Harvey’s are not the first, and they won’t be the last23 January 2026

Comment / Gardies and Harvey’s are not the first, and they won’t be the last23 January 2026 News / Cambridge ranks in the top ten for every subject area in 202623 January 2026

News / Cambridge ranks in the top ten for every subject area in 202623 January 2026