Place-hacking: activism for a modern era?

The trial of a postmodern Spiderman highlights how night climbing has moved beyond hedonistic thrill-seeking to posing serious questions

Dr Bradley Garret, an Oxford academic on trial for breaking into London’s disused tube stations and raiding data stores, is a figurehead for the fast-growing global subculture which numbers around 20,000 “urban explorers” or “urbexs”.

From climbing to the top of the Golden Gate Bridge to scouring arms dumps in the Mojave Desert, this eccentric movement is based on the joy of discovery, the thrill of danger (both of prosecution and physical harm), and the search for beauty in objects and landscapes not designed for human eyes.

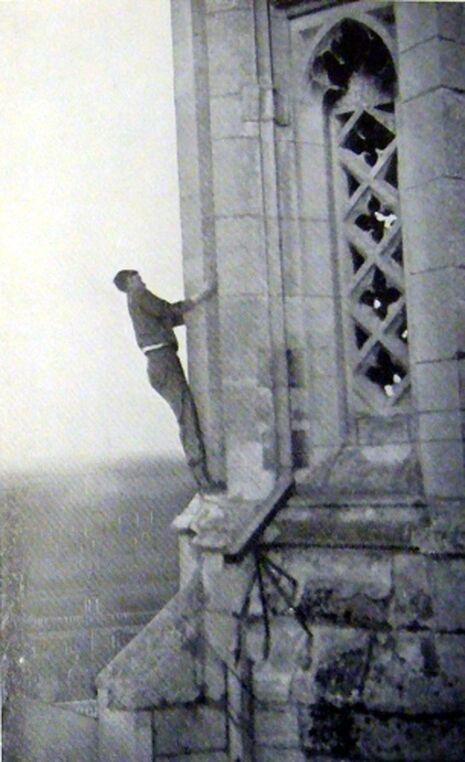

It’s easy to dismiss such activities as a reaction against a cotton wool upbringing. Urban explorers are typically educated and privileged, and it is arguably no coincidence that some of the pioneers were 1930s Cambridge students, immortalised in Noel Howard Symington’s book Night Climbers of Cambridge. The book was recently reprinted and has become something of a cult favorite. The Guardian’s Sam Jordison argues Cambridge’s night climbers formed the other side of the Brideshead Revisited caricature: instead of “morning coffee in the cafés, beer drinking and hilarious twenty-first birthday parties” there is “a jumble of pipes and chimneys and pinnacles, leading up from security to adventure”.

Indeed, modern explorers’ online photos and videos do little to dispel the picture of urban exploring as the sole preserve of an unengaged elite. Highly stylised images of Detroit’s car factories or London’s docklands have been termed “ruin porn”. They glorify industrial heritage and the “beauty” of decay but show little thought to the suffering of those who worked there or the pain that the closure of these industries caused.

Other images look forward to a post-apocalyptic and dystopian future. Photos include explorers silhouetted like Batman on top of skyscrapers looking down at the city below, or else lurking alone in a dripping culvert, hood up and face in shadow. These pictures are compelling and evocative but they also represent a detached and dehumanised view of the city.

However, such analysis risks concealing more important meanings underlying the movement. In this quantified and accounted world, the very concept of exploring – let alone urban exploring – is oxymoronic. Every inch of the world’s surface can be accessed from a computer and the wildernesses that do remain, the final frontiers of space or the deep ocean, are far beyond the reach of ordinary individuals.

We live in a knowledge society in which risk is continually mitigated through everything from health and safety legislation to insurance packages. Paradoxically, these tools which are designed to protect us also make us more aware and more fearful of the dangers that we know we cannot avoid. The effects of such certainty on our mental well-being are unknown. As evolutionary anthropologist Hillard Kaplan notes, humans evolved to thrive on the instinctive evaluation of risk and uncertainty. Our best decisions are often made on the spur of the moment.

Perhaps it should not surprise us, then, that there is something refreshing and even cathartic about uncatalogued danger in the place that’s meant to be safest and best-mapped: the city. Critics of urban explorers speak of risk-seeking behaviour, but perhaps it would be more accurate to describe it as meaning-seeking. Urban explorers also begin to challenge the growing disparities of power and wealth that have accompanied technological achievement.

Over the past thirty years cities have been sectioned and stratified. Recent campaigns against “anti-homeless spikes” and the design of park benches to discourage rough sleeping are a small part of the wider picture. Private space has been gated and public space has been privatised.

Space is increasingly a viscous substance through which the rich or connected can move more freely and even cheaply than others. A visit to the “public” viewing deck of the Shard costs £90 for a family, but the smartly dressed cognoscenti can visit the restaurant for a comparatively reasonable £60 meal overlooking the city. It pays to be rich.

However, while the rich and powerful may have purchased the view, the city is not theirs to buy. London’s shape, size and visual layout is the product of all its citizens rich and poor going about their daily activities. Through trespass, urban explorers have the ability to challenge and change perceptions of ownership and the division of public and private space.

In his 2013 book, Dr Bradley Garrett describes opening the hatch on the seventy-sixth floor of the Shard and seeing London spread out beneath him. He spent the night for free, thereby reclaiming the right to the city.

Of course there are ironies and contradictions in this narrative. The stories and pictures produced by explorers make everything from sky scrapers to abandoned tunnels appear edgier, sexier and more marketable. They are a small movement making demands for freedom of movement – which for reasons of safety, security and privacy niether can nor should be allowed. However, none of this detracts from the message that, at least in theory, the city belongs to its citizens and that it should be as accessible as possible.

News / Government announces £400m investment package for Cambridge25 October 2025

News / Government announces £400m investment package for Cambridge25 October 2025 News / Climate and pro-Palestine activists protest at engineering careers fair25 October 2025

News / Climate and pro-Palestine activists protest at engineering careers fair25 October 2025 Arts / Why is everybody naked?24 October 2025

Arts / Why is everybody naked?24 October 2025 News / Cambridge don appointed Reform adviser23 October 2025

News / Cambridge don appointed Reform adviser23 October 2025 Comment / On overcoming the freshers’ curse22 October 2025

Comment / On overcoming the freshers’ curse22 October 2025