What happened to Kate and Caitlin?

Charlotte Taylor thinks power can be cultural not just political, as Women’s Hour release an uninspiring list of the 100 most powerful women in Britain

It’s that time of year again when industries give themselves pat themselves on back – the Awards season. Every year I am disappointed with the nominations, bored during the ceremony and left with a feeling of dissatisfaction when the inevitable winner takes the statuette. Yet the next year I am once again drawn into this cycle of anticipation and inevitability in the vain hope of surprise or approval.

This year I was given fresh hope as Women’s Hour decided to add to the accolades with the inauguration of their 100 most powerful women in Britain list. I eagerly followed the panel as they debated on the program. The judges included Eve Pollard, Oona King and Dawn O’Porter, media savvy women from a range of social and working backgrounds – which seemed a promising sign for those hoping for an interesting, modern, stereotype busting perspective of power.

Inevitably, the list did not deliver on its promise placing, as almost anyone would have predicted, the Queen at the top of the list. The majority of the women on the list belonged mainly to the business sector – with Elisabeth Murdoch and Moya Greene (CEO of the Royal Mail) ranking in the top 20 – or were involved in the political running of UK, while some of the few cultural representatives (including Adele and Clare Balding) appeared somewhat arbitrary and tokenistic. The stereotype of what constituted power remained as close-minded and limited as ever. The panel had stuck with a distinctively conservative view of power, where the focus was primarily in the business, political and economic arenas.

Perhaps this is not surprising considering we are entering the age of the triple, and probably octuplet, recession. Power is now more than ever a commodity only purchased with money. The list reflects a broader sentiment that places emphasis on the traditionally powerful sectors of politics, science and the economy, laying culture to wayside as something extraneous and unimportant. But does this really mean that power truly lies in the hands of an elite few?

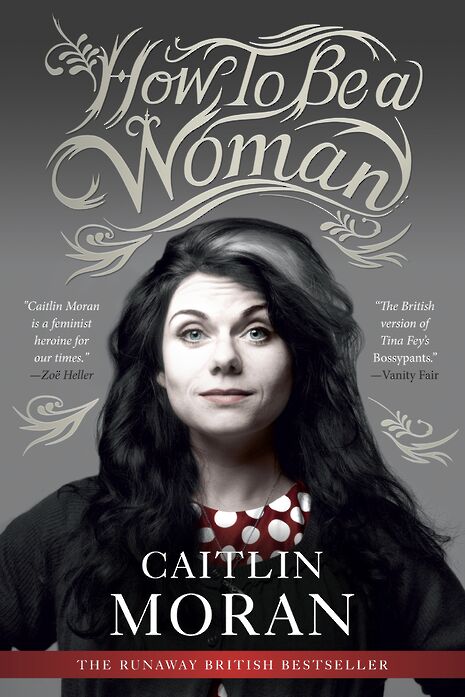

The panel judging the list decided that influence and power should be treated as entirely separate concepts, and therefore judged the 4000 names they has been given in terms of control in Britain. While such power is clearly important is misses a key point: power is just influence in a particular system. Does a CEO or a Royal really have more power than Caitlin Moran, whose book on feminism has introduced a falsely tarnished concept to a new generation of teenagers? This outdated concept of power does not in any way reflect Britain as it really is today.

The most powerful women are not only those in the grand palaces of state, but those whose influence we choose to follow and celebrate. Jessica Ennis did not make the list despite becoming a role model to many around the country and Kate Middleton was excluded while Alexandra Shulman (the editor of British Vogue) ranked in the top half, despite essentially having the same influence. By choosing to consider influence and power as separate entities the panel had excluded one of the most powerful sectors of all: culture.

Fundamentally the problem the list presents is not merely its content, but the fact it exists at all. Eve Pollard noted that the list seemed to suggest that women have “gone backwards” in terms of equality with men in gaining the top jobs. Her comments could be applied to the wider context, and the existence of a separate power list for women once again suggests that too few women would make a general list, thus necessitating the existence of a special list for women on their own. This list may provide a conservative view of women and power, but more worrying is the broader trend it reveals in which women are still lagging behind their male counterparts regardless of how the list is compiled.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025