Dawkins, double standards and dualisms

Richard Dawkins’ new children’s book is more than a little hypocritical

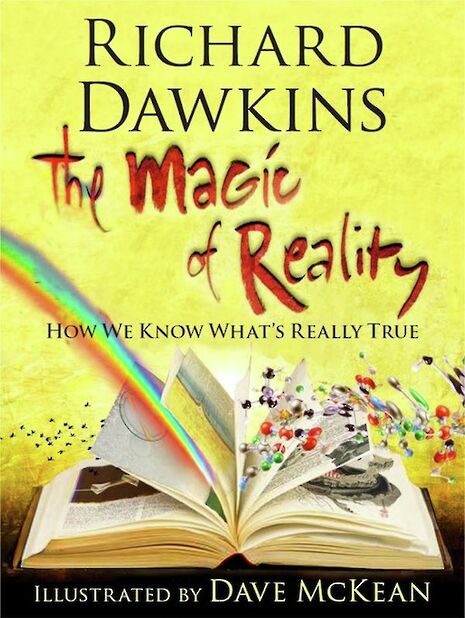

Richard Dawkins is dealing in double standards. In last year's Channel Four documentary Faith School Menace? he urged society "to respect a child's right to freedom of belief." Simultaneously he was working on his latest book The Magic of Reality, reformulating his brand of militant materialism for a "family audience".

Throughout the book, Dawkins is hesitant to mention religion by name. Instead, he alludes to it in passing, tarring the established theologies of the major religions with the same brush as quack remedies, magic tricks and even Cinderella's pumpkin coach. Critics accuse him of "the public abuse of faith." When he describes the Virgin Mary as "a kind of goddess of the local religion," you can see why.

Religions have much experience teaching children about the 'big questions'. Dawkins has caught on and is copying their model of indoctrination. But what rankles is that he doesn't admit as such: he hides his metaphysical agenda in a lavishly illustrated tome about the wonders of science; religions tend to be slightly more open as to what they're about. Yet there remains something unsettling in both cases: neither the theists nor the atheists are letting children think for themselves. In fact, Dawkins' latest move raises an interesting question. How should we be educating young children about the variety of worldviews on offer?

Dawkins modestly admits his limits in the realm of science, saying he isn't a cosmologist so he doesn't understand the big bang himself. But he fails to avoid a dictatorial air of authority on matters of underlying philosophy; as one review aptly put it, he has "shifted into 'wise granddad' mode". The writing is symptomatic of Dawkins' position at one extreme of an unnecessarily polarised media debate. The question of science or religion is a false dichotomy, a dualist approach fortified by extremists on both sides. They either preach to the converted or quarrel with their enemies; rarely does anyone change their mind as a result.

The more interesting distinction is between those that think that everything is knowable and those that don't. Dawkins asserts that it is "lazy, even dishonest" to suggest that "no natural explanation will ever be possible". It is also anthropocentric, even arrogant to suggest that humans can understand it all. In education and in debate, it is perhaps those that bear their knowledge with humility that are most likely to influence opinion.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025