Where’s the contemporary art we deserve?

We need to support artist more, especially in this time of troubles

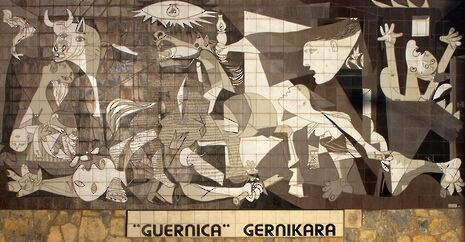

“The formal possibilities of art have been worn out.” These words, delivered by Grayson Perry in an interview with the Radio Times in 2013, are among the most depressing I encountered in researching this article. Art has invariably been a way in which we express ourselves differently, separate from traditional forms of protest, allowing expressions of unrivalled depth and power. The greatest works of art have frequently arisen from tumultuous periods in our political and economic history. This can be seen in the carvings and paintings of men such as Durer and Cranach the Elder, produced during the chaos of 16th century reformations, or, during the Counter-Reformation a century later, in the Baroque architecture of Borromini. In more recent years, we have seen powerful works of art emerging to comment, critique or re-enforce political conditions, such as Malevich’s Black Square, Picasso’s Guernica, or the work of the Guerrilla Girls. What, therefore, do we need in 2017? What light can art shed on our own time of turbulence?

“The greatest works of art have frequently arisen from tumultuous periods in our political and economic history.”

I should point out at this juncture, to my many art historian friends, that I am aware that art doesn’t solely reflect political realities, nor the whims of individual patrons or buyers, but offers a radically different insight into the past and indeed the present. With this disclaimer from a historian art enthusiast, we will press on.

How do we actually consider contemporary artists and their creations? Honestly, as with many artistic periods, we treat present day art with suspicion and caution. Take Damian Hurst for example, whose name is usually followed by the word ‘charlatan’. This is not irregular; we are all aware of the difficulties artists like Van Gogh and ‘El Greco’ had in promulgating their work in their own epochs, but to me 2017 feels different. Where are the contemporary artists we deserve? Is Grayson Perry right that traditional forms of expression have become jaded, giving way to new radical artistic practices?

I don’t think so. In 2010, the artist and theorist Michelangelo Pistoletto wrote an article tackling just what “art’s responsibility” is. In it, he questioned whether it should reflect ecological concerns, or take on ideas of race and ethnicity. For this, he looked at the 2002 movement ‘Love Difference’, an artistic programme seeking to challenge racism and bigotry between Mediterranean countries and peoples. These ambitions seem honourable, but their work was never exhibited in major institutions like The MoMA, Prado or Tate Modern, nor did it receive the coverage or respect that a Turner or Matisse exhibition might expect. While we should cherish, research and marvel at the work of great masters, we must, as Pistoletto concludes, give more opportunities and platforms to young exciting artists.

Ultimately, I think this comes down to how we perceive art and the artist. Even here at Cambridge, History of Art is a subject with fewer than thirty students per year, and those who study it are frequently asked if their degree is part practical, or if all they do is look at paintings all day, rather than studying something serious like economics or politics. This view could not more inaccurate, but it is a product of art being perceived as the domain of the culturally elite, far removed from comprehensive education or even those outside of London. This problem is only heightened by the government’s desire to cut Art History A Level (though it was thankfully saved, albeit in a cut back form), alongside the painful austerity that has been forced upon many art and theatre companies over the last decade.

We need art to be taken seriously, for everyone, not just the few. In an uncertain period for lesser-known artists, photographers and sculptors, we must all do our best to support local creatives. This might mean heading down to see your friend’s work at that exhibition they’ve have been banging on about, or just giving up an evening to see your friends in their new short which they’ve spent the last few months of their life on, on top of all their university work. This might seem marginal, but support now could mean a radically different future for currently under-appreciated, unknown artists. Through their work, we can view the world around us from a new, challenging and fundamentally different lens

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025