No one has the right to choose a child’s religion – least of all the state

No child is born religious, but look beyond your student circles, says Carl Wikeley, and you’ll see that many are still convinced parents have the power to enforce belief

What are the problems with Theresa May’s educational reforms? Social mobility? A disproportionately negative impact on the poor? While these are all real issues, surprisingly few people will ask questions about the concessions given to religious groups.

I have heard worryingly little concern over the allowances that May’s plans give to the Catholic Church and other religions. Even in Cambridge, the concerns are largely about the negative effects the ‘reforms’ will have on the poorest in society. Outside of the student bubble, these religious concessions are hardly discussed. But this doesn’t reflect the fact that religion is, and has been, one of the primary obstacles to all forms of human progress.

What this oversight does reflect is the incredibly slow progress of reason in our society. Between 2004 and 2015, the percentage of Britons who self-define as atheists has risen only slightly, from eight per cent to 13, according to a YouGov poll. This, in conjunction with the number of self-defining, Christian God-believers remaining relatively constant (at around 43.8% per cent, according to a British Social Attitudes survey), paints a starkly different picture to the one many of us experience at university. If, however, as the study suggests, the majority of Britons do not believe in God, then why are more people not concerned with the regressive steps proposed by May?

In what has essentially become the small print of her plan, the Prime Minister proposes to lift the ban on new Catholic schools being founded (even though almost one third of new academies have a religious grounding), while also lifting the 50 per cent cap on faith schools – which prevents religion being a discriminating factor in at least half of the intake.

The Catholic Church has long lobbied for these changes, largely arguing that there is demand for parents to be able to choose whether or not their child attends a Catholic faith school. While not wishing to lapse into ad hominem attacks, it would seem that May’s upbringing as the daughter of a vicar is not a negligible factor in these latest proposals. Having observed the undeniable facts, is it not impossible for the government to justify rolling back limitations of faith schools?

Well, the real problem lies not with the lack of awareness over these specific proposals, nor with the belief that one should be able to practice one’s own religion, but rather at a more fundamental, logical level: even among the 49 per cent who do not believe in a god, there is a common notion that the child of a Christian is a Christian.

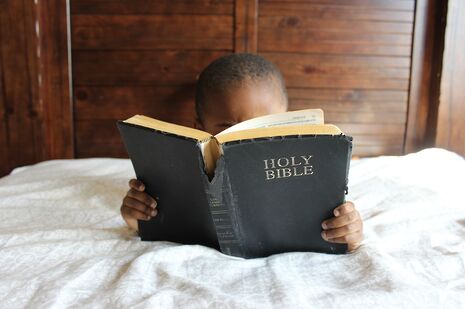

No child is born a Christian, or a Jew, or a Muslim, but the right to enforce this has been taken for granted since the inception of organised religion. Of those who are not religious, and who may have a problem with the new plans set out by the government, nowhere near enough choose to tackle this misconception.

The trouble is, even among non-believers, this commonly-held belief of parental agency is prevalent. Why shouldn’t a parent bring up their child in their own faith, as they believe is right? In attempting to convince others of the fallacy of the parental right to choose a child’s religion, you may come up against common, but poorly-formulated arguments. ‘You wouldn’t stop a parent choosing the clothes a child wears!’, ‘Are you suggesting I don’t teach anything of my culture to my kid?’, and ‘It’s impossible not to make decisions for your children,’ are just some of the misconceptions and straw-man arguments which might head your way.

It comes down to this fundamental fact: the choice of what food to feed a child, what clothes to give it, and what sports to encourage it to play are all important and difficult decisions; however, none of them are as influential, and possibly psychologically or indeed physically damaging, as religion. And to those who are sceptical that religion has negative physical effects on people: try telling that to me – or perhaps to those children who didn’t survive the circumcision.

The argument that if you take your child to church or synagogue, you are not forcing them to be religious is flawed: of course they are more likely to be affected by, or indeed maintain, these beliefs. Faith schooling is not impartial. As I argued regarding Theresa May’s faith school proposals, the fundamental fallacy is that a parent has ownership over a child. This is false, however biologically or psychologically natural it may feel.

It is important to remember that the abolishment of faith schooling is not an enforcement: exactly the opposite is true. Until there is a consensus that no child is born religious, the state has a duty to ensure that these influences do not negatively affect their life.

And so of course Theresa May’s proposals are wrong, not only for their socially regressive approach, or their religious apologism, but the fight against the negative impact of religion in society continues – at least outside of Cambridge.

Is there anything we, as students, can do to promote the wider acceptance of common sense and prevent the oppression of children? Join the British Humanist Society, shout louder about your atheism, and actually start arguing with people! The perception of atheists as ‘militant’ is simply an evolutionary defence mechanism by the religious, in the face of reason. We must challenge the belief that parents may choose their child’s religion.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025