Bolivia’s ‘Taliban’ miners have something to tell us

When Eduardo Baptista escaped an exploding mountain, it got him thinking about how we make ourselves heard

I was sleeping blissfully with my face smack against the bus window when a cacophony of increasingly loud Spanish-speaking voices woke me up. "Blockade, the miners are blockading the road! What are we going to do now?" At first, the answer seemed obvious to me, wait until the miners let us through, which I’m sure would be in a couple of hours. It was 3am, after all. But 15 minutes later, standing outside the bus staring at the hundreds of vehicles lying motionless in front of me, one thing was clear. This was going to be a long night.

Twelve hours ago, I had walked into La Paz bus terminal, ready to haggle for as cheap a bus fare to Santa Cruz as I could get. Santa Cruz’s large houses, wide roads and tropical weather remind me of my home country Portugal, and so I was happy to have scored a 70 Bolivianos (just over £9) bus fare that would give me a break from La Paz’s claustrophobic urban layout, congested roads, and cold, mountain air. Fun fact, did you know that the regional department of Santa Cruz is bigger than Germany? Well, I didn’t, but that probably explains why the estimated journey time from La Paz was 14 hours.

Having been on a 35-hour bus from Lima to La Paz, I arrogantly scoffed at that figure, secure that I would arrive at Santa Cruz in time for a hearty Bolivian lunch. But 12 hours later, I was the one being scoffed at, this time by locals who had no time to explain to a naïve ‘chino’ (slang for an Asian-looking man in Latin America) why the bus drivers couldn’t “just talk to the miners”.

I soon found out why. Walking past row after row of buses, all devoid of passengers, it became clear that these miners had not just put some cones up or organised a sit-in in the middle of the road. I soon started to see huge pieces of rock, presumably from the mountains flanking the roads, strewn onto the tarmac, a mass of smaller debris surrounding them. I have never had the most logical of brains, so I thought to myself: 'these miners must be incredibly strong to be able to move those rocks.’

Before I could voice out my stupidity to a Bolivian family I was walking with, the sound of exploding dynamite made it pretty clear how the rocks had actually ended up on the road. I asked Elvis, a Bolivian on his way to Buenos Aires, if the mineros were blowing the mountain up in full certainty that there was no danger of civilian casualties. Elvis chuckled and said ‘Son, the miners are like the Taliban, get it?’

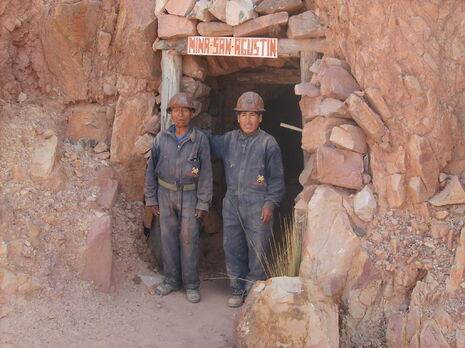

In Bolivia, miners are not affiliated to syndicates with a large membership like their European counterparts. On the way to La Paz airport a week later, a taxi driver by night, miner by day would explain to me that miners are usually organised into cooperatives, groups of 40-50 men who all work together in the same mine.

The daily toils which bind together such a collective mean that, in the driver’s words, everyone regards each other as their 'hermano', or brother. This allows for tight-knit organisation, which facilitates coordination with other similar cooperatives, and a mindset which makes violent action easier to commit to, as the livelihoods of your 'hermanos' are at stake.

From the perspective of a European citizen, it’s easy to understand the exasperation felt by the tens of thousands of Bolivians who were forced to disembark that night. The long-established tradition of collective bargaining, a key factor in Western Europe’s recovery in the aftermath of the Second World War, legitimised a dialogue- rather than violence-oriented policy towards the state within the syndicates representing the European labourers.

From the perspective of the Bolivian miners, however, it is just as easy to see why dialogue would seem to be a pointless course of action. The key element in the successful establishment of collective bargaining in Western Europe was the welfare state and its commitment not to leaving its working-class citizens completely at the mercy of the market. Workers were thus less prone to striking because the state now played an active role in the provision of health care, better education and greater investment in infrastructure.

There is no such provision from the Bolivian state, which was ranked 119th out of 188 countries in the most recent UN Human Development Report. This is why the miners are not the only ones in Bolivia blockading roads. Truck drivers, farmers, and even teachers have all used the mountain side to extract concessions from the government. The fertility of their wives has nothing to do with their form of protest.

Fast forward a few days later and I’m in Philadelphia airport, awaiting my flight to Lisbon. Browsing through some books in a shop to pass the time, I came across an interesting passage in Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed, a book that sets out to investigate the impact of the 1996 welfare reform act on the working poor in the United States. After describing the poverty of millions of low-wage Americans as a "state of emergency", she concludes her work by hopefully predicting that "one day" America’s poor will revolt: but the "sky won’t fall, it will be better for it."

Yet almost two decades have passed, with no such revolts in the US, or Europe for that matter. This contrasts heavily with the uncompromising and slightly reckless actions of the Bolivian miners. I’m not suggesting that American or European labourers adopt quite such explosive methods of protest, but amid the redundancies and austerity measures being adopted by many European states today, the mineros' belief in action over dialogue is worth noting down, now more than ever.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026