Cambridge colleges, snap out of your apathy on sexual harassment

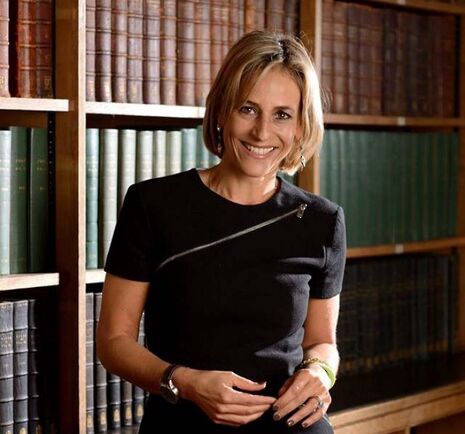

Emily Maitlis met her stalker at Cambridge in 1989, and in 2016 freshers are still meeting theirs

The Newsnight presenter Emily Maitlis met her stalker at Cambridge in Freshers’ Week, 1989. Last Monday, he was sent to prison following over 25 years of bombarding Maitlis and her family with letters and emails, demanding to know why they had never become a couple. Edward Vines, the man in question, was convicted of harassment in 2002, given a restraining order in 2009, and still Maitlis’s two children require a security escort to get the school bus.

And in some remote and sad way, you might feel sorry for Edward Vines. To be in a position where such harassment appears not only reasonable but necessary cannot be a happy one. But of course it was not reasonable. And it was very, very wrong. Vines’s inability to see himself as anything other than a victim, an admirer spurned, means he can’t possibly understand why this is the case.

The implicit threat of stalking, like all forms of sexual harassment, is that it renders the victim powerless. For the stalker nothing, not your comfort, your sense of personal safety, or your right to choose who you have and do not have as part of your life means anything next to their entitlement to pursue you and provoke the reaction they want.

When you know nothing will get in their way, even if for now the behaviour seems perfectly innocuous, you live in a constant state of fear and anxiety – where will it all end? When respect for another person’s comfort or safety is not a limiting factor on a stalker’s behaviour, the very worst you can imagine begins to become entirely plausible.

All this runs through your mind all the time. Like when the guy who’s following you sits down yet again directly opposite you in the exact same place in the library and in the college dining hall. Even though the guy who was following me has now left Cambridge, I’m writing this piece anonymously because that fear still grips my insides. And the case of Emily Maitlis makes you wonder – how much have Cambridge colleges changed their response to instances of harassment since the early 90s?

Not very much, I would say, and change is long overdue. Simply put, colleges need stronger, zero-tolerance policies on harassment, with clear penalties. They need to make this clear in Freshers’ Week to incoming students – in the same way a representative of the college already makes the college’s policies and rules on fire safety and length of residence sternly and abundantly clear.

I had the luck to discover that my college had a good sexual harassment policy when I needed to use it, and that tutorial staff were very supportive and highly motivated to implement it properly. Unfortunately, as Nathalie Greenfield’s powerful article only last week in The Huffington Post, telling the story of her rape in 2015 while a student at Cambridge, highlights, this approach is still rare among Cambridge colleges.

And even in my case, the policy was hard to find before I approached my tutor. I was pleasantly surprised by the great support I received only after I’d made that leap into the dark with the love of family and friends behind me. It took a lot of confidence. Would I be believed? Would my concerns be dismissed as trivial? Would I end up being the one put on trial? Most are not so fortunate as I was.

The same problem of leaving far too much up to students themselves goes for sexual consent workshops. Placing the burden of organising and delivering these squarely and solely on the shoulders of students themselves, without any explicit support of the college, is grossly inappropriate. Sure, JCRs and welfare officers throughout Cambridge do a fantastic and valuable job. But at the end of the day they are peers, and expecting them to find a way to command that kind of authority is an enormous ask.

Sure, we students are of an age when we seek our own independence, and need to start taking responsibility for and seeking solutions to many of our own problems. But sexual harassment and assault are not things we should be expected to deal with on our own. These borderline criminal and fully criminal activities are not on the same level as learning how to balance your university workload, deal with a break-up, or take responsibility for your mental and physical health needs.

University administrations declining to get involved, and putting sexual harassment and assault on a level with normal, formative aspects of young adult relationships is a large part of the reason why they continue to be endemic on college campuses. As Nathalie Greenfield’s article points out, this is not just an issue in the US. It’s happening here too.

Also, it’s not like our colleges afford us a great deal of independence in other aspects of our lives, which makes the whole ‘hands-off’ approach when it comes to sexual harassment even less convincing. At my college, we are charged a termly ‘Kitchen Fixed Charge’ of £180 to subsidise catering, and any attempt at renegotiation is met with ultimate refusal on the grounds that the ‘communal dining experience’ is too important to sacrifice, and something we must be ‘encouraged’ to partake in.

Now, while I personally don’t mind being financially ‘encouraged’ to consume food, financially coercing me into eating my meals 12 feet away from the man who has been harassing me over the past couple of weeks is something I have a lot more of a problem with if insufficient action is being taken to let him know his behaviour is not acceptable.

In effect, you can’t create this college community, in which everyone is forced to live in such proximity, in which potential harassers are given such easy access to you, and then throw up your hands at the idea of setting boundaries and standards of behaviour upon which that unusually close community will operate. It’s not about politics, or coddled young students. It’s an entirely reasonable expression of the duty of care colleges have.

So please, Cambridge colleges, don’t let this keep happening to us.

News / Sandi Toksvig enters Cambridge Chancellor race29 April 2025

News / Sandi Toksvig enters Cambridge Chancellor race29 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025

News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 News / Zero students expelled for sexual misconduct in 2024 25 April 2025

News / Zero students expelled for sexual misconduct in 2024 25 April 2025