On Cambridge’s ‘perfect’ league table score

Does coming top in league tables really make Cambridge the best university, or is the reality more complex?

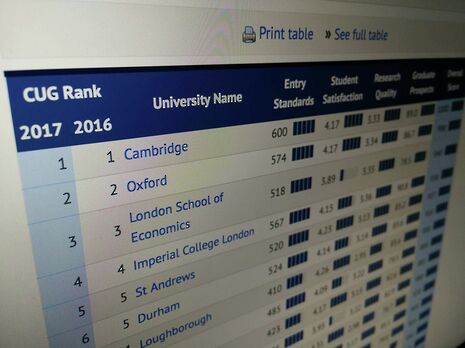

At the start of this week, Cambridge University was voted top of the Complete University Guide (CUG) league table, scoring the maximum 1000 points. In addition to this success, last month the University also added another trophy to its collection, in being ranked the world's leading institution for Mathematics, History, and Archaeology, in the latest QS World University Rankings. But this news is not by any standard 'breaking' nor is it by any definition 'exceptional': Cambridge has been rated top by CUG six years in a row, and little has changed within the QS World rankings either, with Oxbridge dominating British universities. It would be more ground breaking if Cambridge fell out of the top ten, and was replaced by Anglia Ruskin, which only managed a standing of 110 in the CUG League.

While topping the CUG league table is no doubt positive publicity for the University – not to mention a nice quote and caption to add to the prospectus – the question remains: what does being 'top' mean? I often ponder the realities of living and studying at a so-called top university and whether it has made any difference to my student experience and student welfare. I certainly consider the university's 'greatness' and 'perfection', particularly when I wake up in the morning to no hot water, or when I attend a lecture without a fully functioning projector and lights. The University seems to struggle at times to maintain its ‘perfect’ rating for student welfare, especially when I have to work a full twelve hour shift in the college library to make a weekly essay deadline, or turn up at a lecture only to find the lectern vacant. In reality, the university may well be top in league tables, assessed by independent bodies, but the day-to-day living and experience of Cambridge is hardly perfect.

A lot of the independent assessment determines 'research quality and 'research intensity'. While research is of course vital for the University and for the world in many ways, its impact on my own and other undergraduates’ experiences of university is unlikely to have any immediate effect (unless the research was conducted in aid of improving student kitchen facilities or faculty toilets). I also think it is important to question the impact of academic research in terms of my employability. The University may well help prepare me for a career in academia, but what if I decide to pursue a different type of job? What value does 'research' hold in the 'real' world?

Furthermore, what does it actually mean to attend a university top in research? One factor is that you are able to get the best and most qualified lecturers, supervisors and fellows at your colleges and facilities – some of whom are world leaders in their fields. This is indeed exciting, especially if you are as fortunate as I am and have weekly one-to-one supervisions with such eminent academics. Living in Cambridge also brings with it a buzz of innovative energy: every week there is a new idea published, and a sense of much intellectual creativity in the colleges and University Library. But aside from experiencing symptoms of what is commonly known as the 'Cambridge bubble' I find it hard to see what other impact word leading research will have on my employability after graduation.

Other universities, despite not being top in the league tables, focus more intensively preparation for future employment. While the Careers service at Cambridge does offer some provisions, the standard of career planning and advice does not seem superior to that at universities. As a result, it becomes difficult to explain how Cambridge would be top of the league tables if it didn't score phenomenally well in its research, a factor which barely impacts the everyday life of the average undergrad.

Interestingly, if we consider the student satisfaction surveys we obtain quite a different ranking of universities. For example, the league table for student satisfaction recently carried out by CUG offered a number of surprises: Cambridge or Oxford were nowhere in sight of the top. The first three places were instead occupied by the University of Buckingham, Surrey and Keele, which feature not even in the top ten when observed in the CUG league table, which features Cambridge, Oxford and LSE top.

Student satisfaction is rated on individual happiness, support networks, feedback and personal development. Personally, I think that Cambridge does offer all of these features, particularly in terms of feedback from supervisors, and an excellent student to staff ratio. However, the league table of student satisfaction raises an interesting point: universities can be rated in more meaningful ways than research and academic excellence.

Despite their flaws, I feel league tables should be taken seriously, especially as many employers use them as a good foundation to pick future graduate employees. However, league tables are not the be all and end all. No university is perfect, regardless of a league table’s designation of a ‘perfect’ score. Even Cambridge, a global hub and world leader of research, does not have appropriate heating in some faculty libraries or standard kitchen facilities in all college accommodation. It certainly doesn’t have 'perfect' student satisfaction from some who view it as a 'bubble' of stress, toil and gloom.

As a naive Year 13 student, I remember looking closely at league tables and purposefully selecting universities which were high in the charts and also in the Russell Group. If I could write a letter of advice to my Year 13 self, I would stress not to take league tables as a definitive guide to one’s future university experience. Having said that, I am of course proud to attend the CUG's number one university, we just must remember that the league tables are indeed limited. To any prospective student reading, I urge you to leave behind preconceptions and focus on where you want to go, rather than to where the league tables direct you.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025