The campus novel trap

Felix Armstrong argues that Cambridge internalises and preserves its own fictional stereotypes

The campus novel is now so popular in our culture that it has become almost invisible: a transparent gloss on everything we consume, painted not only onto fiction but television and film. From Normal People to Saltburn, mainstream art is increasingly hemmed into the university campus, or, more often than not, the four corners of an Oxbridge court (or quad, for our neighbours across the M25).

Even if not by name, every consumer of culture is aware of the campus novel: any work of fiction taking place around a university or college, whose popularity seems to stem from its blend of coming-of-age stories with the intensity of student environments.

As our generation sees more and more stories told within the constraints of the university campus, we expect to recognise more and more of its tropes in our own student experience. The popularity of the campus novel has meant that the conventions of the genre have seeped into our cultural consciousness: we are aware of them, we expect them, whether or not we’ve read them ourselves.

"Campus novels influence student life directly, as students and universities both play into, and allow for, their conventions"

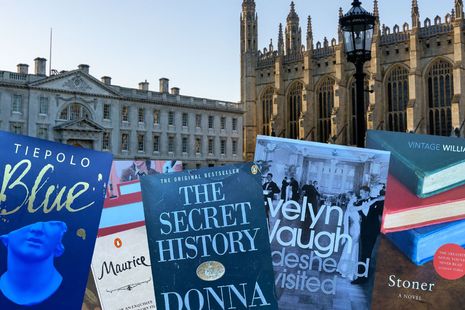

We recognise the snobbery of the elite demonstrated in Brideshead Revisited, so expect it in the Pitt Club; we recognise the financial inequality of The Secret History, so expect it as more students are forced towards grants; we recognise the brooding loneliness of both of the above and many novels besides, so expect it from ourselves as the deadlines pile high, and the library books higher. Let’s for all of our sakes hope that Saltburn fever dies fast, else we’d better use our shared bathrooms more carefully.

This is not just to say that campus novels are good or that they relate accurately to the student experience. Rather, I believe that the genre runs so close to the environment it fictionalises that the relationship has begun to flow both ways. Campus novels influence student life directly, as students and universities both play into, and allow for, their conventions.

The simplest example of Cambridge appealing to its own fictionalisation is the privilege within campus novels: the way elite universities are portrayed as playgrounds for the gilded youth. A mere glance at recent headlines shows the University to be parodying its own campus novel stereotype. Adverts for a wine connoisseur at Corpus, instructions for students to layer up with gilets, and defences of drinking club hazings prove that ours is a university which plays to the gallery.

Looking deeper into the mechanisms of campus novels further proves how Cambridge falls into this trap. The two novels I’ve mentioned so far, alongside a stack of others (such as Lucky Jim, Stoner, and Small World) are patently male, presenting a macho, tortured-artist view of academia and student life which, while obviously informed by our University, informs it too. The misogyny present in Cambridge is rightly still debated, for example with regards to the “Sidgwick girlie” stereotype, because our generation has been taught and retaught the supposedly masculine nature of the university campus.

"Let’s for all of our sakes hope that Saltburn fever dies fast, else we’d better use our shared bathrooms more carefully"

The same goes for many more conventions of the campus novel. The genre teaches us that universities like Cambridge are places where isolation reigns (see Stoner), sexuality should be straight-jacketed (Tiepolo Blue), and diversity is invisible (almost any campus novel could be named here, but take Maurice).

Such universities, then, are readers. They pick up the next paperback with their face on it, flick through it, and (even if subconsciously) emulate it. This campus novel trap means that elite university culture is stuck in a loop, such as it has been internalised by our society and projected back onto these institutions.

This makes it ever easier for Cambridge to sit comfortably within the status quo, to act as the genre says it does, and forever will. While every student has enough reading on their plates, perhaps this leads us to read our own University that bit more intently, and to catch it when it’s performing itself.

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024

News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024

Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024