How children’s literature understands the book

Fondly flipping through tattered picture-books, Eve Connor muses on how children’s literature can fashion the book into an object

Kettering was a childhood treat for my mother because it had good shops, including Marks & Spencer and a bookshop. She spent her change buying sweets and Enid Blyton stories or browsing the odd library sale. When my class brought in The Famous Five to read in primary school, I glowed with pride at my inherited bumper edition; as a girl, my mother had crafted a book sleeve out of wallpaper taped in four places to the inside covers. The wallpaper was cream and bumpy. I loved the texture, as I loved the stamped library card still inside and the cigarette smell. I never progressed beyond the few chapters we read in school and my lasting memory of the book is its characters, relentlessly smooth-faced children chirping about ‘hols’ – an abbreviation I adopted into my vocabulary – and ‘queer,’ a word I had no cognisance of but thought beautiful. I couldn’t understand why my classmate’s copies preferred ‘strange.’

“I searched the bookshelves for that universal language text, the picture book”

This summer, I spent four days in Nice with a friend, a treat of our own. ‘Good shops’ were plentiful but expensive to broach. We inhabited Aldi and Carrefour, opening our mornings with a baguette and slab of brie, the curtains closed to keep out the sun. Evenings sounded like the electric fan, a film studio affair propped on a velvet stool, at full blast while I picked through the day’s photos. An object card at the Matisse Museum caught my eye: ‘Matisse conceived the book as a totality, an architecture made up of elements that balance each other.’ After a dinner of too-thin spaghetti, kidney beans, and sweetcorn, I searched the bookshelves for that universal language text, the picture book.

Recent French children’s literature differs little from its English counterpart in appearance, overlooking the obvious language factor. Bold text wiggles across glossy paper. There may, however, be something to say about sensibility. I did not conduct a comprehensive study. I asked my friend to translate Le pigeon qui voulait être un canard (‘The Pigeon Who Wanted to Be a Duck’) by Lili and Soledad Bravi and the story’s unexpected ending tickled us. Rather than the pigeon, Gédéon, realising his self-worth after failing to blend in with the ducks, decides to try again the next day as a chicken. He is Scarlett O’Hara abandoned on the red-fired threshold of her estate insisting ‘tomorrow is another day’ – and he is Sisyphus. One must imagine Gédéon happy.

“We want illustrations, pop-ups, and a ‘FROM THE LIBRARY OF’ sticker inviting us to write our names in coloured pencils”

To be clear, I love Le pigeon qui voulait être un canard. I love the ending and I would have loved Gédéon even ignorant of the language. The illustrations are fun (Gédéon staring out at the reader with globular eyes across a double-page spread) and touching (shedding a single tear with his makeshift flippers discarded beside him.) It is scary for a writer to admit I grasped much of the story without reading a single word. But if writing also means story, structure, and pacing, what does reading mean? If we ‘read’ paintings and ‘read’ a room, what are we doing?

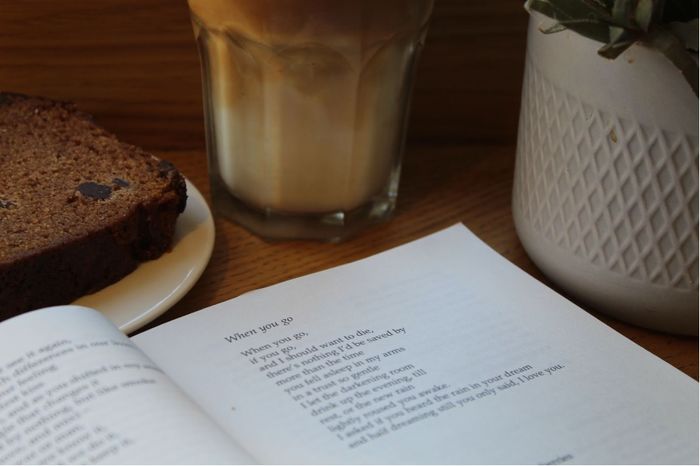

From the dimpled faces of my mother’s Enid Blyton to Gédéon’s beak, children’s literature understands the book as an object because its readers expect one. Form and content intertwines. We want illustrations, pop-ups, and a ‘FROM THE LIBRARY OF’ sticker inviting us to write our names in coloured pencils, and sometimes we wallpaper the covers. Matisse’s Lectrice à la table jaune (‘Woman Reading at the Yellow Table’) holds an open book illustrated simply. The shapes are smudged, possibly stick-people or a vase of flowers, spreading across both pages. The woman smiles, and it could be any volume. It could be a children’s book.

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024

News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024

Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024