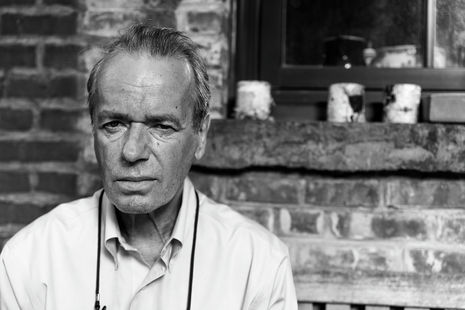

Martin Amis: seeing both sides of the controversial writer

In light of Amis’s death this May, David Quinn dissects the work of the writer to see if there’s something beyond his cynical facade

“The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity. Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite.”

Known for his verbal dexterity and casual, comic turns of phrase, it seems natural to sum up Amis’s life with one of his own pithy quotes – just as he did for so many authors before him. But there’s more to the man than his witty misanthropy. While he wasn’t always likeable – and sometimes downright deserved the scorn literary critics gave him – he was just as capable of being humorous and humane as he was controversial.

Given his subsequent infamy as an author in his own right, it might seem hard to imagine the expectations placed on the son of Kingsley Amis. Amis Sr. had struck lucky with “Lucky Jim” in 1954, taking his position in a literary scene populated by men like everyone’s favourite Mr. Miserable, Philip Larkin. Teaching at Peterhouse in the ’60s, Kingsley Amis became emblematic of the typical literary figure of “an angry young man turning old” - giving his son the perfect foil for rebellion.

“It’s hard to imagine a clearer analogy for breaking with the past”

After an unpromising education, Martin Amis couldn’t quite make his first novel The Rachel Papers – which he admitted was somewhat autobiographical – into much more than the observations of a clever and fairly narcissistic teenager. Nevertheless, after the birth of his writing career in 1973, Amis’s voice would only grow in strength and distinctiveness across the decade.

However, with Amis Sr. apparently throwing a copy of Martin Amis’s 1984 novel Money across a room in disgust of its breakdown of perceived “literary taste”, it’s hard to imagine a clearer analogy for breaking with the past. Money sets out the clearest display of what would become Amis’s style. With Amis believing style was “embedded in your perception” as a writer, the humour and witticisms of his novels could evidently not be purged out to make it more serious, nor added in post.

“His rebellion against his father did not prevent him from becoming part of a new establishment”

This fixation on style led to many of his most celebrated novels – but also a perception of literary stubbornness. By the early 2000s, opinions on Amis swung into cynicism. There is some irony that his rebellion against his father did not prevent him from becoming part of a new establishment. While his literary chums – including the equally witty and equally frustrating Christopher Hitchens – set out to transform the stiffness and self-importance of their seniors, they inevitably formed a new clique of white, middle-class male writers.

Lacking the thought and self-awareness that raised his prior observations, Amis’s political essays merely reacted, while his characters became acted upon; they were not actors in their stories. Female characters in particular suffered from a lack of autonomy, bearing much of their male author. The trait runs through his work: characters work more from appetites than motivations. Sometimes this could produce dazzling social critique, but it could just as easily produce self-parody.

Summing up the various, elusive figure behind the words is difficult without returning to his own phrases. Amis’s last novel, Inside Story, offered a new side to the writer, revealing him to be more humane than literary critics potentially expected. Filled with anecdotes and reflections, the novel offers wit beyond the bombast of his previous output. Unsurprisingly, mortality was the central theme. In his ’30s, at the height of his style, Amis said that “death gives us something to do” – but his maturity did add a new poignancy to his remark.

Again, it seems best to allow Amis’s prose to speak for itself. “It all starts to look very beautiful now that I know I’m not going to be around indefinitely.” At least, for that moment, he hit upon the eternal.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 Features / Beyond the Pitt Club: The Cambridge secret societies you have never heard of16 November 2025

Features / Beyond the Pitt Club: The Cambridge secret societies you have never heard of16 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 News / A matter of loaf and death17 November 2025

News / A matter of loaf and death17 November 2025