Queens’ Arts Festival is a true bricolage of delights

Grace Cobb reviews Queen’s Arts Festival finding it to be a triumph of artistic talent and fascinating concepts

Stepping into the Fitzpatrick Gallery for this year’s Queen’s Art Festival, I’m confronted by the theme spelled out in jumbled cardboard letters: Bricolage. Its meaning? Rejecting conventional, traditional artistic mediums and the constraints of reality to devalue art and assert the beauty and value of the everyday. That’s not to say that the work displayed in this year’s exhibition isn’t cohesive or artistic – the myriad of conceptual inspirations and array of media are united in their shared celebration of the unconventional beauty found in incongruous fragments of the everyday. Interlacing the diverse experiences, cultures and mediums of artists across Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin, community is at the heart of an exhibition emanating with art’s potential to forge connections across space and time, an ethos enacted in its sub-themes: collage, hands, bodies, mythology.

“Community is at the heart of the exhibition”

As I approach the first few works, a snapshot of disordered tools and artisan items indiscriminately lit up in the sunset shifts to disquieting documentation of the collision of urban and rural worlds, leaving me with “Finding Gleam”, a futuristic digital collage of a girl stretching towards a sustainable utopia beyond the land of fast fashion. Moving from mundane objects’ surprising beauty, to a jarring reminder of their disastrous effects, and culminating in an artwork where freedom from this becomes reality, this narrative captures the whole exhibition’s chronicling of the loss of nature’s sublimity if we don’t “LOVE the hideous in order to find the sublime core of it”, as its manifesto demands. Despite emphasising “you are what you make”, by answering the climate crisis’ demand for conscious creation with endless evidence for the variety and innovation this can produce, the exhibition ultimately poses an empowering challenge to “make what we could be”.

Introducing you to bricolage is the familiarity of “collage”: inherently childlike, yet imbued with godlike potential to create new lives from old materials. Tying together personal photos, handwritten poems, graphite drawings and typed letters, the canvas for Holocaust Memorial Day poignantly unites people through media. Among the striking purple, the visible fingerprints left on each heartbreakingly personal line, letter and thread of string not only make the stories of survivors and victims of the Holocaust and genocides in Rwanda, Cambodia and Darfur feel raw and tangible, but manifest the personal marks of the creators from Robinson and Lucy Cavendish who reassembled this loss in art.

“Inherently childlike, yet imbued with godlike potential to create new lives from old materials”

Threading such collages into the works grouped under “hands” is a shared sense of childlike, liberating, and unrefined creation epitomised in “Potato Prints”, a touchingly intimate charcoal piece which overwhelms me with hazy nostalgia for childhood afternoons blissfully spent jabbing fingers into paint, free from expectations of poignancy or pretence. As my eyes shift to the next work – centring instant noodles in an absurdly abstract digital collage interrogating the facade of social media in Thai culture – sentimentality comes jolting into contact with a biting social criticism, which nevertheless emanates with equivalent personal significance.

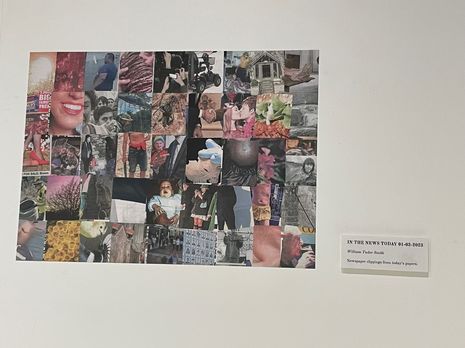

A festival preoccupied with how our sociopolitical identity is informed by the ways we construct and consume is naturally underscored with a variety of critiques, ranging from anti-capitalist explorations of groceries’ artistic qualities to Orwellian plasticine shorts satirising media indoctrination. William Tudor Smith’s “In the News Today” assembles clippings from newspapers across the spectrum on the exhibition’s opening day which, pasting it onto the wall as I approached, he told me he had finished only an hour ago. Ripped out of context, the snippets range from a woman’s heeled feet sticking out over an armchair to a microscopic close-up of hamburger meat, inevitably peppered with several trauma-soaked crime scenes. Inviting you to read into the possible stories behind each fragment, this mish-mash of consumerism, objectification and violence captures a society united by discordance.

Devaluing art is taken to new levels in the final section, “mythology”, which recycles traditions as well as materials, transforming ancient figures and fantasies into cross-cultural, contemporary reimaginings of futurity and sustainability. Profoundly imprinting my memories of the festival, Santiago Tricks’ highly self-reflective short film scrutinises both the aestheticisation of the lives of Indigenous Mexican people by other artists, and his own potential commodification of the culture he celebrates. This visual and aural collage of Totonaco art and traditional songs in polyvocal harmony with Queen’s College choir captures the essence of bricolage’s refusal to seamlessly blend cultures into consumability.

The exhibition’s cycle of constant collaboration is continued in the response room: armed with a Pritt stick and array of magazines, photos and fabric scraps, I take up the challenge by pressing an advert for Kew Gardens which recalls summer visits with my mum next to the title “Paradise Lost”, which I’m currently studying for my degree. Pasting a piece of myself into the exhibition, I feel privileged to become another thread in the tapestry of pre-existing people, pictures and stories this festival weaves together into a bricolage of a brand new future.

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024

News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024

Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024