‘His own devoted arm’: Remembering Thom Gunn in LGBTQ+ History Month

Arts writer Jamie Chong reflects on the poet’s legacy as a powerful voice for queer loss, love and life

“IF I DIE OF AIDS – FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA”. David Wojnarowicz’s words, drawn on a pink triangle on the back of his denim jacket, condemned the FDA’s inaction on AIDS research. As LGBTQ+ History Month draws to a close, it is important to look back on our struggle towards queer equality and how the body, as Wojnarowicz demonstrates, became a political battlefield for the cause.

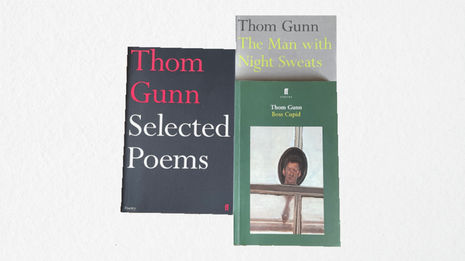

Perhaps the writer who most eloquently captured the grief of the AIDS epidemic was former Cambridge student Thom Gunn (1929–2004). A poet known for his technical virtuosity, mastering both formalist and free verse, Gunn explores subjects outside the range of “traditional poetry”: the daredevil antics of bikers, surfers catching a wave and acid trips, to name a few. His refusal to conform to contemporary standards and fearlessness in discussing his homosexuality (especially in the stifling atmosphere of Article 28) make him the pre-eminent voice for the pain and loss caused by the AIDS epidemic.

“Gunn’s insistence on unflinching accuracy makes for a piercing yet profoundly emotional portrayal of the AIDS crisis”

Gunn’s collection The Man with Night Sweats contains powerful depictions of his lost friendships. As each poem unfolds, Gunn shows how queer identity in the 80s played out on the body. A two-week vigil at the bedside of his close friend dying of AIDS inspired the elegy “Lament”: 116 lines of heroic couplets recounting in heartbreaking but unsentimental detail his friend’s deterioration, how “in your cheek appeared the true shape of your bone / No longer padded” and “death” came “by drowning on an inland sea / of your own fluids”. Gunn’s insistence on unflinching accuracy makes for a piercing yet profoundly emotional portrayal of the AIDS crisis.

There is the lingering air that all of this did not need to happen, that there is so much future left unfulfilled. In “Lament”, his friend is “not ready and not reconciled, / Feeling as uncompleted as a child / Till you had shown the world what you could do”: an acutely human emotion often left out of political discourse around AIDs. Though Gunn made no explicit political commentary, in voicing the emotions brewing in the community, he humanised all the victims of AIDS while governments remained silent, while the media actively demonised gay men (branding HIV “the gay plague”) and while MPs like William Frank Brownhill could call to put “90% of queers in the ruddy gas chambers” without repercussion.

Gunn refuses to negotiate queer identity. Each poem acts as a defiant defence of queer physical intimacy, even amid all the loss, pain and social condemnation. The collection opens with “The Hug”, an embrace “in which the full lengths of our bodies pressed: / Your instep to my heel / My shoulder-blades against your chest”, and closes with a celebration of the body: “this fair-topped organism dense with charm, / Its braided muscle grabbing what would serve, / His countering pull, his own devoted arm”. While The Man with Night Sweats is indeed concerned with death and disease, it remains passionately committed to celebrating what it means to be queer.

"His art was ready to memorialise the life of a community"

Queer loss, love and life are the driving force behind Gunn’s poems. As Clive Wilmer explains, literature was Thom Gunn’s way of navigating painful experiences: “When his world was shaken by crisis, as it was by AIDS in the 1980s, his art was ready for it.” His art was ready to memorialise the life of a community. In “Memory Unsettled”, Gunn recounts this interaction: “‘Remember me,’ you said. / We will remember you.” I hope we will.

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024

News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024 Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024

Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024