How does animal suffering make you feel? I’ll take a wild guess and say: not great. Violence towards animals is widely condemned, seen as barbaric and unethical. We have laws that protect animals from abuse, and social norms that shame those who mistreat them. After all, how could a kind, morally just person ever hurt an animal? Of course, a kind, morally just person is still allowed to eat animals.

The beliefs many of us hold about animal suffering are in sharp conflict with our social norms around animal consumption. This makes meat consumption fascinating from a psychological perspective, as a clear example of cognitive dissonance – that discomfort produced by holding two contradictory beliefs at once. In this case, the tension arises from believing that hurting animals is wrong, while also believing that eating meat is acceptable.

There are two ways to resolve this discomfort: behavioural change, or rationalisation – and for most people, rationalisation is far easier. This is achieved through a range of psychological strategies, often described as meat-related cognitive dissonances, that many of us use, largely subconsciously, to justify the discrepancy between caring about animals and consuming them.

“Many of us use meat-related cognitive dissonances to justify the discrepancy between caring about animals and consuming them”

Perhaps the easiest way to cope with the cognitive dissonance of meat consumption is to distance oneself from it. The structure of modern society makes this remarkably easy: factory farms are physically removed from consumers, and unlike in hunter-gatherer societies or early agricultural models, those who eat meat are no longer confronted with the violence it required to produce it.

Social pressure further reinforces this distance. People are often wary of sharing information about animal suffering – when the realities of farming are raised, the resulting negative emotions are frequently redirected towards the messenger, rather than towards behavioural change. And because our society is designed to allow this avoidance, even those with overwhelming access to information and the privilege to change their behaviour (read: Cambridge students) often choose to ignore animal welfare issues. As psychologist Albert Bandura observed, “harming others is made easier when their suffering is not visible.”

To sanitise the act of meat consumption, we rely on language that separates the animal from the food product. The phrase ‘factory farming’ alone evokes machinery rather than living, sentient beings. We call meat from cattle ‘beef’ and meat from pigs ‘pork’ – terms that distance us from the animals themselves.

“Consumers of meat products avoid cues that might trigger empathy for farmed animals –because empathy has the inconvenient potential to put them off their dinner”

Interestingly, this linguistic separation is largely reserved for mammals. We are more comfortable naming chicken and fish directly, perhaps because their greater evolutionary distance from humans makes empathy easier to avoid. This distancing extends beyond language to presentation: studies have shown that meat advertised alongside images of the animals that produced it provokes more empathy in consumers, and thus, is less popular. In effect, the consumers of meat products avoid cues that might trigger empathy for farmed animals – because empathy has the inconvenient potential to put them off their dinner.

Yet the presence of vegans and vegetarians forces meat-eaters to define their identities – not simply as ‘normal’, but explicitly as consumers of meat. Their existence undermines the claim that eating meat is essential to human life or necessary for good health. The idea that we can’t get enough protein without animal products has been disproven so many times that it’s a laughable argument – still believing that one can’t eat a healthy, balanced vegan diet requires a fair amount of wilful ignorance. The visibility of vegans and vegetarians challenges the idea that meat consumption is unavoidable.

In response, mockery or eye-rolling becomes a reflexive, defensive reaction. Dismissing those who choose not to eat meat allows meat-eaters to deflect attention away from the discomfort raised by their presence – and from the cognitive dissonance that this discomfort exposes.

“The visibility of vegans and vegetarians challenges the idea that meat consumption is unavoidable”

Scientific research has shown that pigs are among the most intelligent domestic animals, outperforming even three-year-old children in certain problem-solving tasks. Yet the living conditions in which pigs are kept are among the most inhumane faced by domestic mammals. Farrowing crates barely allow sows to move, while practices such as teeth clipping and tail docking are routinely used to manage behavioural problems rather than address their environmental causes.

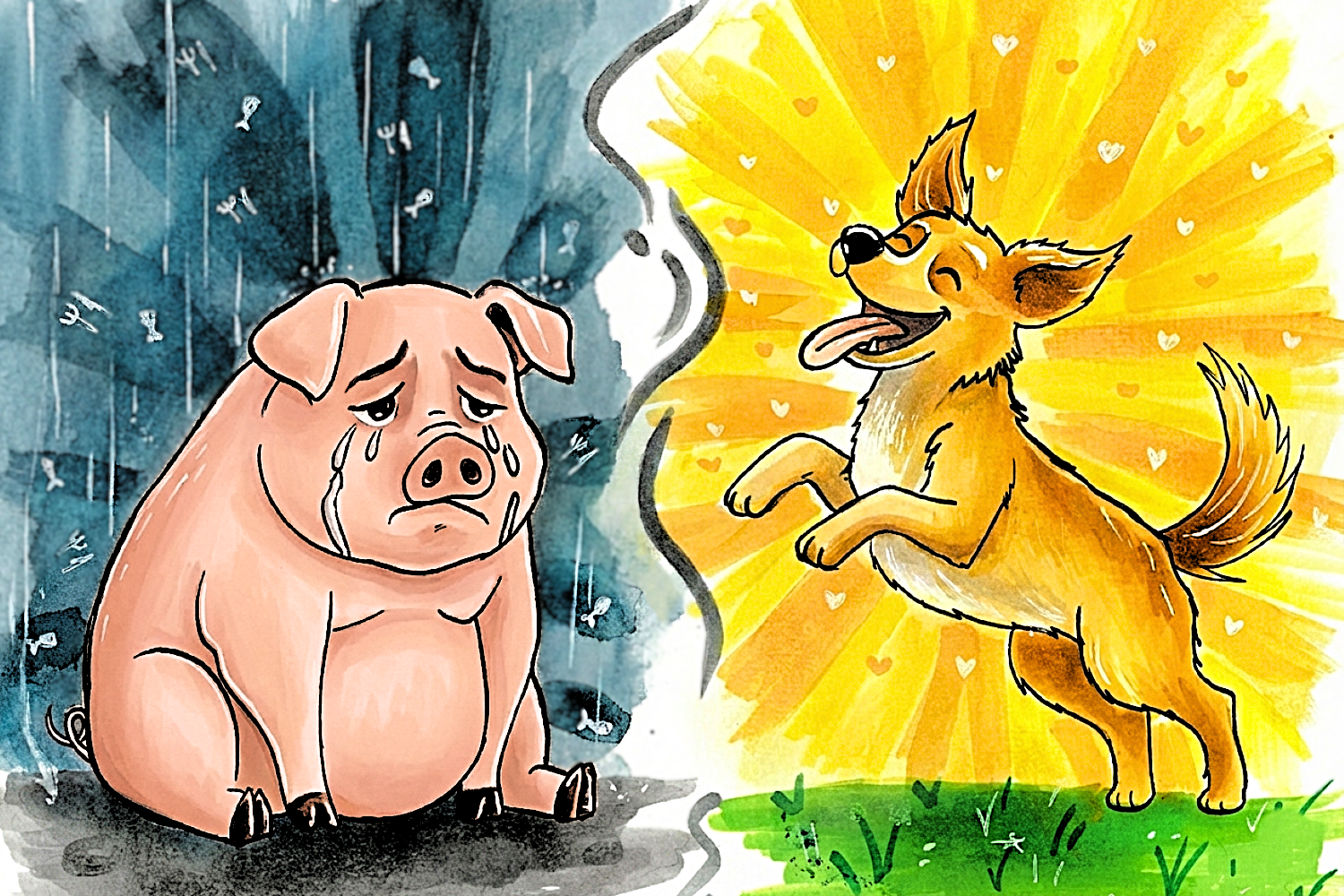

This treatment is rarely questioned, not because pigs lack the capacity to suffer, but because moral concern for animals is shaped less by their ability to feel pain than by the roles we assign them. Dogs and cats are our companions and therefore protected from consumption; cows, pigs, and sheep are farm animals and therefore deemed acceptable to eat. The logic is circular. We wish to consume meat without guilt, so we craft narratives that explain why certain animals (and not others) can endure poor living conditions and deserve to be slaughtered for human use.

“There is nothing natural about the sheer volume of meat we consume, nor the constant availability we expect”

Appealing to social norms is a common strategy for justifying meat consumption. When the strategies outlined above begin to fail, what often remains is to claim that eating meat is natural – and therefore inevitable. Humans are omnivores, and evolved to eat a diet that includes both plants and animals, so in a vacuum, meat consumption can be described as ‘natural’. But there is little that is natural about modern factory farming. There is nothing natural about depriving animals of adequate living conditions because doing otherwise is not economically viable. There is nothing natural about the sheer volume of meat we consume, nor the constant availability we expect. And if anything distinguishes humans from other animals, is it not our ability to allow empathy and rational reflection – rather than instinct alone – to guide how we treat others?

It is therefore unsurprising that many people perceive vegans as annoying, self-righteous, or condescending. Few of us welcome challenges to our moral frameworks, and it is far easier to retreat into defensiveness or irritation than to re-examine deeply ingrained habits and enact meaningful behavioural change.

Ultimately, we all have the autonomy to choose what we consume. But that autonomy comes with the responsibility not to remain wilfully ignorant of the ethical consequences of those choices, or to avoid information simply because it is uncomfortable. So, the next time you’re shopping for groceries or ordering a meal, it may be worth pausing to consider how you would feel if, instead of a neatly packaged product, you were confronted with the animal itself.