At Cambridge, the Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy has big dreams for integrating artificial intelligence into its work. From automated detection and analysis to pattern-finding in the choreography-like structure of steels to searching random atomic structures for the next battery material, AI has permeated materials science. Crucially, if we want to avoid climate breakdown, researchers will need to address the material challenges in sustainability technology, and AI could play a big part.

This is because advancements in our carbon capture and battery technology are fundamentally limited by our materials not being good enough, and large corporations like Google, Meta and Microsoft are investing millions to use AI to find new, better materials. But does materials science even need AI? To find out how practical our materials AI ‘dream’ is, I spoke to two Cambridge researchers at the forefront of AI in materials: Chris Pickard and Shijing Sun.

I first spoke to Professor Chris Pickard, a world-leading computational researcher in materials structure prediction. Chris has conducted research to find a better battery cathode material using machine learning. I asked him how useful AI is to materials science. He replied with gleeful precision: “Well, materials science already is an AI field. Since the 90s, the department has been using neural networks and machine learning techniques to solve real world problems.”

For Chris, machine learning (a subset of AI) has always been instrumental in his work and the AI hype is just being stoked by advances in generative large language models, like ChatGPT. In the past few years, Chris has found success with machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), which accelerate his materials search.

“Well, materials science already is an AI field”

In 2023, Google DeepMind, Google’s AI technology team, claimed to have discovered 2.2 million new materials. This paper demonstrates how AI could soon lead materials discovery globally. However, when the paper was inspected by scientists, they found that thousands of the compounds contained scarce radioactive elements or were unstable, making them useless for actual devices. In a response article, Sir Anthony Cheetham, former Goldsmiths’ Professor of Materials Science at the department, and Shijing’s PhD supervisor, said: “It’s one thing to discover a compound, and a totally different thing to discover a new functional material.”

I relate this story to Chris. He nods slowly. “My opinion is that it would be a shame if we didn’t try something because we assumed it wouldn’t work.” Chris continues to describe the dialogue between two parties: the old guard (experienced scientists) and the new (exciting AI research). When a new AI paper overclaims their findings out of excitement, material scientists are quick to find rebuttals, and that’s natural.

“It’s one thing to discover a compound, and a totally different thing to discover a new functional material.”

I still had reservations: surely the AI boom is overhyped and destined to crash? After explaining this to Chris, his eyes light up, eager to tackle the deep question, and he tells me about hype cycles. He explains how he saw the nanotechnology and graphene hype attract a lot of investment, but how that seemingly dissipated as the challenges became apparent. “Usually these technologies are not doing much more than what researchers were already doing in the first place.” He pauses with effect. “However, I think the difference with AI will be the advancement in chip technology and computation generally.”

If the AI bubble does burst, Chris hopes that researchers will finally get cheaper access to high-performing GPUs that would otherwise be used by data centres. Furthermore, the tools associated with software developed by companies like Nvidia will remain. However, there’s still a problem: how do we actually make the materials Chris predicts? The reality is that there’s a bottleneck – enter Dr Shijing Sun, the newest researcher in the materials department, fresh with ideas from her time at Silicon Valley and the University of Washington in Seattle.

“That’s currently the void I’m trying to bridge,” says Shijing, bursting with confidence and approachability. “On the one hand, we have these large AI-powered databases of really interesting materials, and on the other, the experimentalists are in the lab trying to make them.” Her solution to make this process quicker: automated labs!

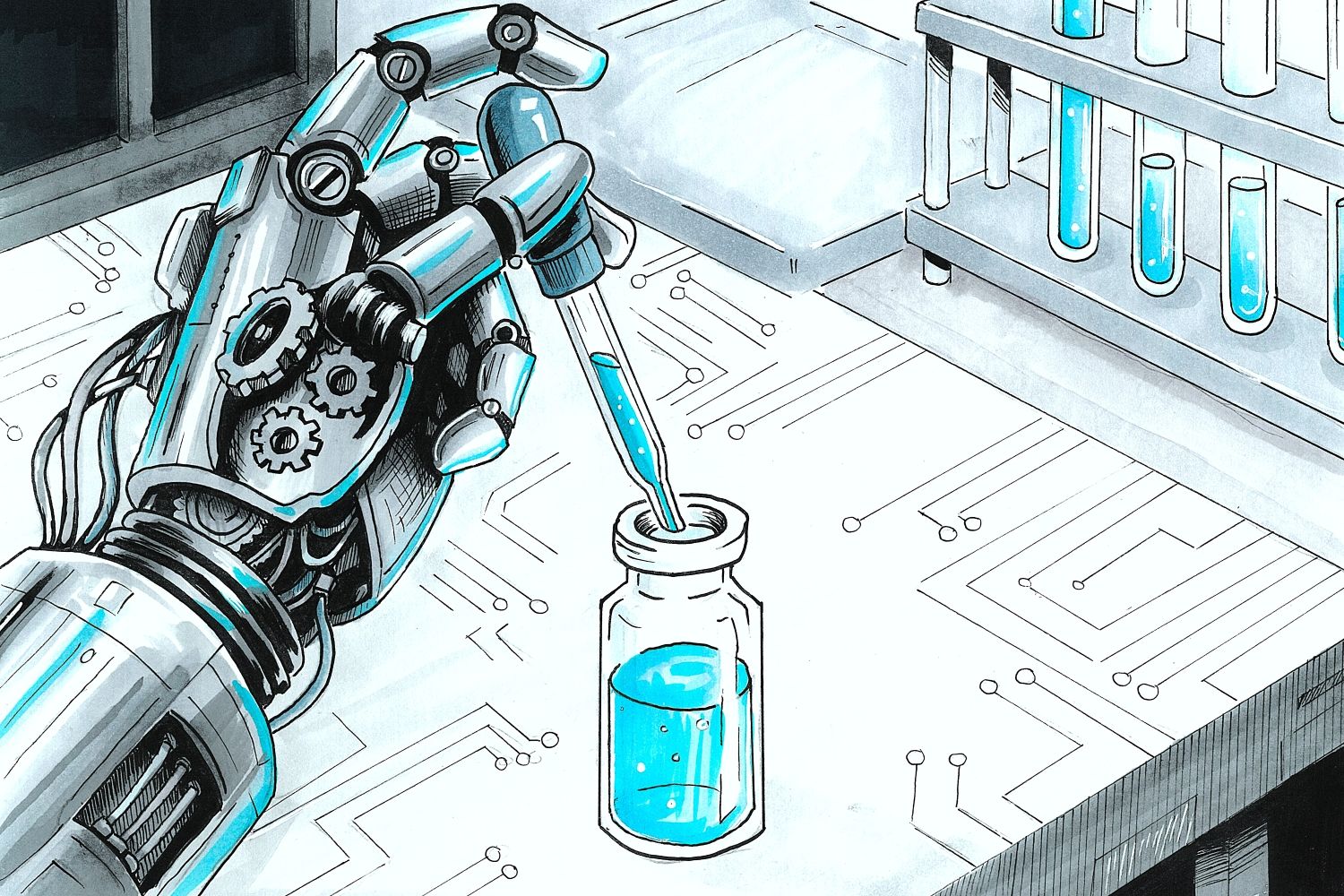

“The idea of working with a scientific robot is a bit like having a kitchen robot,” she jokes. Shijing gets a cooking order, perhaps a new battery material, and she then creates a set of instructions detailing how to make it. “What’s amazing is that every stage in that process can involve computation. AI can search large databases for interesting structures (the dish), generate the ingredients and recipe, and robotics can be used to make the product, with AI giving it the instructions.

“The aim is to foster an ecosystem where automation and AI empower human scientists to realise meaningful scientific discovery”

And what does an automated lab look like? Shijing’s current setup consists of a benchtop box with many sensors and a robotic arm roughly the size and shape of 3D printers. This can then perform automated pipette operations and other functions – is this the future of the lab?

“It’s still very, very early stage,” says Shijing with consideration. She explains how scientists are already good at making physical decisions, and so the aim isn’t to replace them. Instead, automated labs can upscale and accelerate production of new materials with the aid of current scientists. “The aim is to foster an ecosystem where automation and AI empower human scientists to realise meaningful scientific discovery.” Let’s say you were unsure whether it’s better to use 10% of A or 10.1% of A in a device; this trivial difference could take hours for a poor PhD student to investigate by themselves. However, with an automated lab, it can test not just those samples but also 100 other compositions. The benefit is clear for optimisation.

“There are tasks that humans excel at, and others where robots perform better. For example, unscrewing a bottle is trivial for a human, but it is not as straightforward in today’s lab automation.” Robots could also make mistakes, but Shijing discusses how robots tend to make the same mistakes, allowing her to distinguish between random and systematic error. “The robot records every action and parameter, so we can trace how errors arise, learn from them and correct them.”

But doesn’t AI use a lot of water and energy? Well, Shijing’s focus is on energy materials, trying to address the very problem of increasing energy demand … does solving the problem using one of the culprits make any sense?

“To be sustainable, we can’t excessively use resources. However, powering a robotic lab is not necessarily more energy-intensive than a conventional lab,” reasons Shijing. She explains how instrument efficiency and research productivity can account for this: she is always using scientific intuition to optimise the energy use. But more generally, she does consider energy use in data centres. “Data centres do take a lot of energy, so it’s definitely not out of consideration.”

It’s an optimistic and radical approach, but as Chris says, it would be a shame not to try something because we’re sceptical of it. Shijing’s brilliant work could be the very answer to our AI dreams. With lab automation, researchers could tackle sustainability challenges and the AI revolution head-on.