It was during lockdown that I purchased Florence Given’s Women Don’t Owe You Pretty. A friend had shared a trendy, hot-pink, feminist infographic on their story and, admittedly, my first thought was God, wouldn’t that book look good on my bedside table. It was a thought that surely would have made Florence herself cringe. Nevertheless, I entered my card details and, sure enough, three days later I snapped a photo of the book alongside a matching pink and yellow coffee cup to post to Instagram.

Did I read the book? Of course I did — I might have bought it solely for aesthetic purposes, but as an English student, I can’t always afford to be that vapid. It was as though Given’s voice was scolding me, and specifically me, from beyond those funky pink sketches and from the little epigrammatic (or rather Instagrammatic) bursts of choice-feminist quotes that I incarcerated within a strip of pastel purple highlighter. I was ashamed.

“Women might not owe you pretty, but Given had provided me with a cover pretty enough to adorn my bedroom and accessorise my social media self”

Given was urging me that my ‘invasive, expensive, time-consuming and at times painful beauty rituals’ were transforming me into an object and ‘men don’t respect objects’. All the while, I was embellishing her pages with pastel highlighters and setting them alongside decorative flowers and skin-care products. Women might not owe you pretty, but Given had provided me with a cover pretty enough to adorn my bedroom and accessorise my social media self. I had transformed the book itself into another beauty ritual.

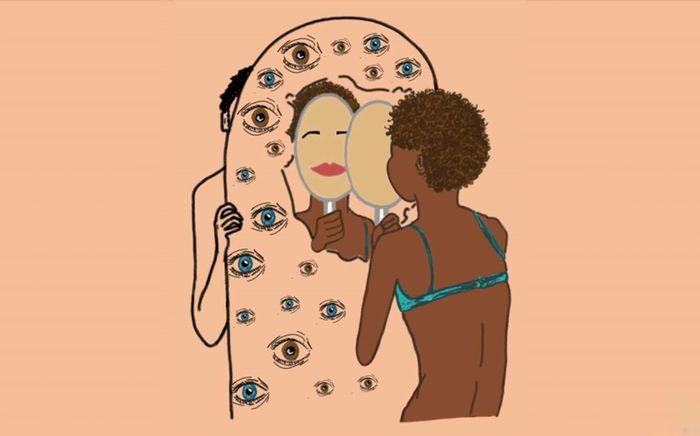

I didn’t need a wake-up call from Given, however; Margaret Atwood had already provided me with a glaring, jolting one. Atwood forced me to look in the mirror and see ‘the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head.’ Atwood taught me that ‘you are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.’

I already knew that threading my eyebrows, paying for haircuts that made my male friends gasp when I told them the price, waxing, shaving, putting on makeup (the list goes on) was excruciating. I already knew that I woke up every day like Euphoria’s Cassie, up at 4 a.m. to perform the ritual of making myself presentable and palatable in the privacy of my room. Cassie’s little ritual seems like a preparation for a showcase, the backstage makeover that anticipates the onstage performance. Yet, it is the application, the preparation, the ritual itself that is the performance. I already know I do these things to myself to become palatable to the outside gaze. So why, then, Atwood seemed to beg me to consider, do I curl my eyelashes before going to sleep?

It doesn’t aid their growth, it doesn’t help them fit the Western beauty standard of thick, luscious eyelashes, and the curl is gone by the morning. I used to think it was just for me, so I could lay there before my sleep and feel, in those few solitary moments, pretty. Atwood taught me that none of these rituals, none of these procedures, will ever be just for me. Sure, they might follow the choice-feminist line of thinking that we don’t wear lipstick to impress the men we see every day, we don’t curl our hair to be appealing to that insidious male gaze, peering from outside. But what about the gaze that peers from within? What about the patriarchal eye embedded so deeply into every feminine-identifying person that always watches, always guides those choices?

Given isn’t entirely blind to this prospect — in fact, Chapter Two turns its back on the book’s premise book entirely: ‘Women Don’t Owe You Pretty. But…’ She accepts that it is ‘easier’ when we follow the rules, make ourselves palatable. She also acknowledges that, for marginalised women, the performance of femininity isn’t always a ‘choice’ but ‘often an act of survival’. She knows, mercifully, that ‘being able to grow out my body hair is, in fact, a privilege’. Given’s apparent solidarity with trans women and women of colour crumbles a little, however, in the face of the book’s allegations of plagiarism, as Chidera Eggerue claims that Given stole the creative ideas of black women, her own ideas, in fact, and begs the question ‘when can black women just have things without people copying?’

“The only real ‘choice’ in choice feminism, for these women at least, is palatability or death. I will curl my eyelashes before I sleep to please the voyeur, or I will die”

The performance of femininity as an act of survival might be one of the only times Given hits the acrylic nail on the head. In pop culture, we are increasingly seeing women letting themselves be raw and real in their frustration at this performance, but unable to let it go. Japanese-American singer-songwriter Mitski Mayawaki, in her song ‘Brand New City’, turns to the morbid realisation that ‘if I gave up on being pretty, I wouldn’t know how to be alive.’ Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s eponymous character in the TV comedy Fleabag breaks down in tears in front of a man she barely knows and yells that ‘I know that my body, as it is now, really is the only thing I have left, and when that gets old and unfuckable I may as well just kill it’ (she also fears that ‘I wouldn’t be such a feminist if I had bigger tits’, but that might be a worry for another day).

The only real ‘choice’ in choice feminism, for these women at least, is palatability or death. I will curl my eyelashes before I sleep to please the voyeur, or I will die. At one time in history, we might have been called melodramatic, or hysterical, to see the rejection of these performative rituals as fatal. It is, by no means, to say that all women feel this way. It is also by no means to suggest that it is fatal to not adhere to patriarchal beauty standards. It is only to say that choice feminism is an impossible fallacy, and might only be a way to justify the patriarchal gaze and to stuff it further down the throats of feminine-identifying people, to internalise it more and more. Women Don’t Owe You Pretty has been returned to its decorative spot on my nightstand after writing this; for now, at least, I think that is where it will stay.