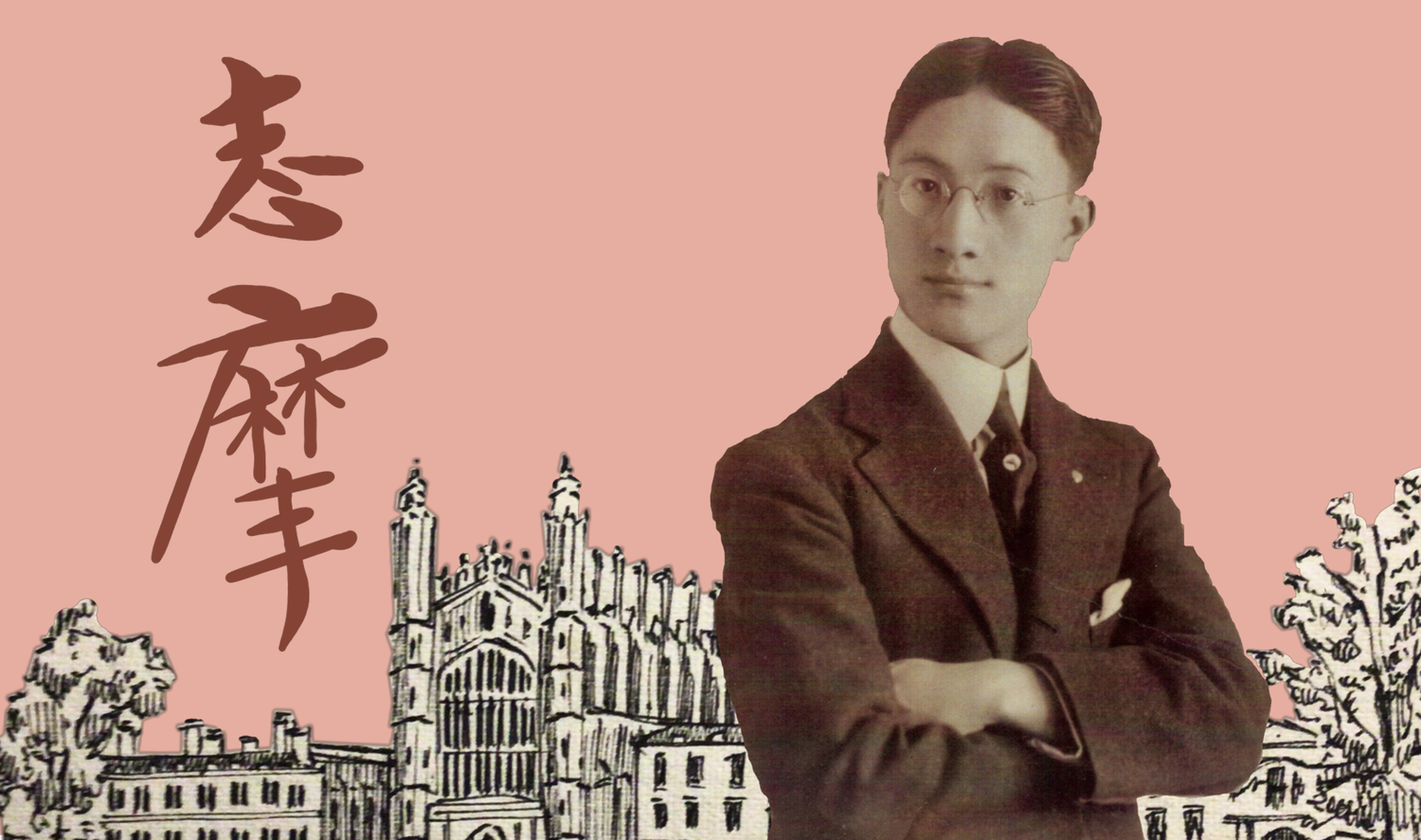

In middle school, every Chinese child studies the famous Chinese poem ‘Saying Farewell to Cambridge Again’. The poem, which contains “The willow is gold on the Backs” and “To dream? Take a punt upriver,” was written as the poet, Xu Zhimo, was leaving King’s for the final time to return east. He died in an air crash near Jinan three years later at the age of 34, and is remembered as the father of modern Chinese poetry. Whilst at King’s, he fell in love with English romantic poetry, and abandoned his study of economics to become a poet.

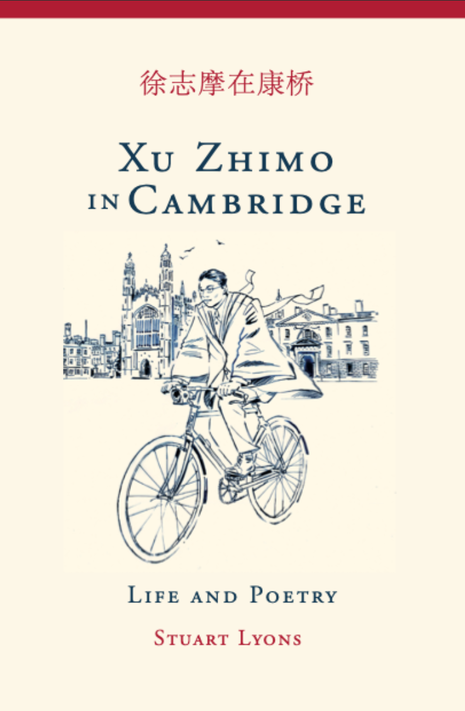

In his poem ‘夜’ (yè, Night), Xu’s admiration for Wordsworth is unambiguous. The poem follows a bird who, arriving at Dove cottage in the Lake District, listens to the conversations of Wordsworth through the window. Lines of Wordsworth’s ‘Personal Talk’ are quoted, and stand out for being quoted in English. Like the majority of Xu’s work, the poem has never made it west. In Xu Zhimo in Cambridge, and two accompanying volumes, Kingsman Stuart Lyons (matric. 1962) has produced a complete translation of Xu’s work, interwoven with commentary, that captures not just the meaning, but the rhythm and idiosyncrasy of the verse. Meeting with Lyons in his home, he confirmed that his is the first English translation for most of Xu’s 201 poems.

“Despite being written in Chinese over a hundred years ago, ‘春’ seems to be about my life”

In ‘春’ (chūn, Spring), Xu writes about walking in the meadows behind King’s, envying the lovers in the grass. I think Xu’s poetry appeals to me because, like my favourite painters, he is capturing familiar experience: in the spring, he walked along the backs between Garret Hostel Lane and Silver Street, he noticed birdsong, and felt lonely. Despite being written in Chinese over a hundred years ago, ‘春’ seems to be about my life. Thanks to my attempt at Mandarin GCSE I am aware of ‘radicals’: small motifs which appear across many characters, implying meaning. In ‘春’ (Spring), the same ‘silk’ radical 纟appears on the left in ‘缱绻’ and ‘绸缪’ in the line “到处是缱绻, 是绸缪” (And love is everywhere, – and being in love). Lyons tells me that radicals “imply that falling in love has to do with a silkiness in the relationship”. Though impossible to translate this implication and visual rhyming, Lyons captures this with tools such as alliteration, and where this isn’t possible, the effects are explained in the notes following each poem.

In Chinese a word can be repeated twice for emphasis or cutesiness. For example, ‘我看看’ is literally ‘I look look,’ but means something like ‘I’ll have a peek’. Xu uses this to near endless poetic effect. This can be subtle to a native speaker, but the challenge to the translator is to convey this effect in a language in which doubling words is much less natural. Of 22 instances in the poem ‘Wild West Cambridge at Dusk’, Lyons translates six of them directly. The outcome sounds so bizarre that it’s as if you are able to read the Chinese – it’s genius.

一个大红日挂在西天

紫云绯云褐云

簇簇斑田田

青草黄田白水

郁郁密密鬋鬋

红瓣黑蕊长梗

罂粟花三三两两

a big red sun hangs on the western sky

purple clouds crimson clouds brown clouds

mottled fields in clusters lie

green grass yellow wheat white fens

lush lush dense dense shagginess

red petals black stamens long stems

poppies in flower in two and threes…

Appropriately, Lyons won an award for his translation of this poem. In line five, Lyons tackles the duplicated characters head-on, and subverts the rhythm at the end of the line: “Xu wrote ‘lush lush dense dense shaggy shaggy’, which would be awful.” Instead, the double gg and ss in ‘shagginess’ capture the visuals.

“A European may see Flanders Field as a mass of red poppies. Xu notes the distinct parts of the individual poppy”

Literally translated, the third line reads “green grass yellow field white water”. Lyons described how he needed to empathise with Xu: “What is he really looking at here, out at Sawston. He’s describing the white fens”; pleasingly, this half-rhymes with ‘stems’. But there is something else fascinating there. The dissection of the landscape into grass, field, and water, or of the poppies into petals, stamens, and stems, is unusual to say the least. Lyons believes this teaches us something about China: “A European may see Flanders Field as a mass of red poppies. Xu notes the distinct parts of the individual poppy.” Perhaps this arises from language: reading Chinese requires you to pick out individual visual objects, each regularly spaced and distinct, whereas English combines items (letters) to form meaning in a less regular way. In translating this, Lyons told me “the Chinese poetry has got to rule, I’m an intermediary.”

Lyons said that he “got a grade A in GCSE Mandarin at the age of 38,” and that “translating was a question of going through the dictionary with a magnifying glass”. Despite this, Lyons said he’s “not afraid of translating Chinese,” and evidently he has no reason to be. Having related to Xu through 201 poems, Lyons described him as “brilliantly precocious, a world-citizen, but very impetuous”. For Xu: “Things had to be as he wanted, he didn’t have mature judgement, either with women or academic relationships.” As is so often the case, it seems artistic brilliance arises in a flawed character. For me, Xu is the model for the beauty that only cultural mixing can achieve. Lyons’ books are already sparking renewed interest in Xu, both in the west and among tourists from east Asia. The interaction between Cambridge and China is closer now than ever, and much of this is owed to Xu’s legacy. Lyons’ trilogy allows us English speakers to understand both Cambridge and China in a new way, and to see our town from the other side of the world.

Xu Zhimo in Cambridge, Last Farewell to Cambridge and 201 Poems are available to purchase at the Shop at King’s and Heffers.