Truth, in art and life, is often ascribed a unitary quality. Yet the Fitzwilliam museum’s latest curative venture, True to Nature: Open-air Painting in Europe 1780-1870 features artists that ‘invite us to understand the different truths they see.’ With the various angles taken, and subjects portrayed, we get the sense that nature cannot be defined by a singular sense of truth, but can be encountered in its varying multitudes. The exhibition takes us through these various different encounters, organised by subject, and method. No singular subject is shown as more significant – demonstrating the multitude of truths that can be found in its artistic representations.

“The collection and curation of these objects were viewed through a similar artistic lens as painting”

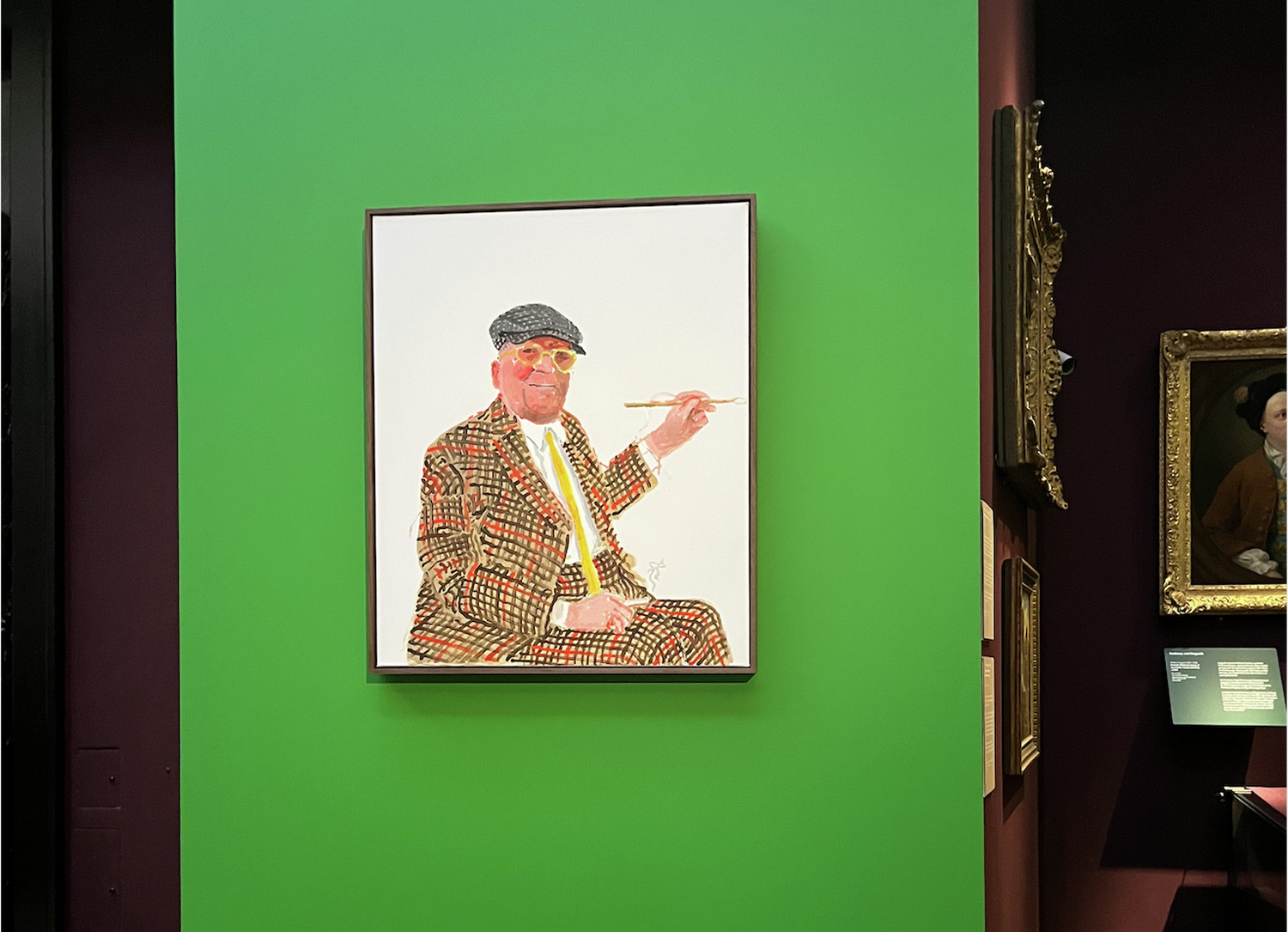

What struck me the most was how innovatively the exhibition is presented, like the Hockney exhibition, it is an amalgamation of traditional curation and more interactive features. Alongside the walls of slick oil paintings are mock-ups of outdoor painting scenarios, such as the one pictured here, directly mirroring the set-up of Jean-Baptise Camille Corot as he, in turn, painted French Landscape Painter, Outdoors at His Easel (c.1860). This layered, clever curation, defines the entire collection, presenting the works not just as individual observations, but as inextricably connected as versions of a momentary, fleeting, truth. Its specific innovation comes from it aspiring to total immersion.

Perhaps one of the most ephemeral of natural subjects is clouds, and this exhibition certainly uses their implications to underline what it means to be ‘true to nature’ in art. In fact, an entire wall is dedicated to the depiction of clouds, combining eighteenth-century, gorgeous sunsets, with time lapses of contemporary artists venturing out and emulating the traditional method of painting en plein air (outside) whilst illustrating their local landscapes. Modern examples within this exhibition are rare, but the Fitzwilliam takes the opportunities digital display has to offer to portray the continuity of this subject as universally thought-provoking. Strikingly, Luke Howard’s 1803 essay Modifications on Clouds is displayed with as much prominence as the artworks itself, demonstrating the importance of both artistic and academic theory on how artists approached their subjects.

Alongside the classical, ‘untouched’ landscapes of figures like Corot and John Constable are ‘built environments’, such as castles, villages, and bridges, where ‘human presence is implicit, even if invisible’, to quote the exhibition’s explanatory text. This outlook ties into much of the Fitzwilliam’s famous collections, such as the several Brughel works, and allows for a distinctly human perspective on nature to remain. Rural societies are ever present, with pieces such as Frederik Sødring’s The Monastery of Alpirsbach Near Freudenstadt (late 1830) characterising its community without having to depict a single person. It is the portrait of unruly, but picturesque domesticity. A Romantic fascination with ruination and remains is found in works such as Eugène Isabey’s Ruins of the Théâtre-Italien After the Fire of 1838 (1839), showcasing the exhibition’s acute attention to both evolving and remaining life.

Traditional landscapes are accompanied by other artefacts, both of physical and digital forms. A section on volcanoes showcases how artists have responded to the fascinating process and subsequent products of volcanic eruption. Not only was the natural phenomenon illustrated through the extremities of light enabled by oil paints, as exemplified by Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond’s Eruption of Stromboli (1842), but also through actual displays of actual igneous rocks and minerals produced by the mirroring events. The collection and curation of these objects were viewed through a similar artistic lens as painting, whilst also of course taking on scientific value in how they reflect the topographical qualities of nature often uncharted through paintings. The exhibition does not shy away from these scientific elements, rather leaning into them, featuring academic books and discourse which accompanied the intense artistic study of these objects and phenomena.

This extends into an entire section dedicated to trees – pieces which both explore its traditional symbolism – strength, longevity, but moreover preoccupied with its relationship with detail and specificity. Bark is transformed from a signifying feature to an emblem of texture in paintings, Darwin-esque records of natural life displayed in the same manner as portraits. There is a sense, in this exhibition, that being ‘true to nature’ is simply keeping an authentic record of what you observe, experience, and feel, in relation to these subjects which cannot be artificially replicated. This exhibition embodies the idea that artwork is the closest you get at projecting and sharing that sense of truth.

“We get the sense that nature cannot be defined by a singular sense of truth”

Yet, throughout True to Nature, we remain aware that it ‘remains a constant, yet is increasingly fragile’, as relayed to us in the exhibition’s initial explanatory text. All of the pieces displayed take on a unique individuality, as moments captured, never to be observed in the same way again – vulnerable as memory. It is this vulnerability, the acknowledgement that these landscapes were captured through artistic creation, but beyond the page or canvas, will gradually fade like clouds, which provides these pieces longevity, a certain, binding afterlife.

True to Nature: Open-air Painting in Europe 1780-1870 is at the Fitzwilliam Museum until August 29th. More information on the exhibition can be found here.