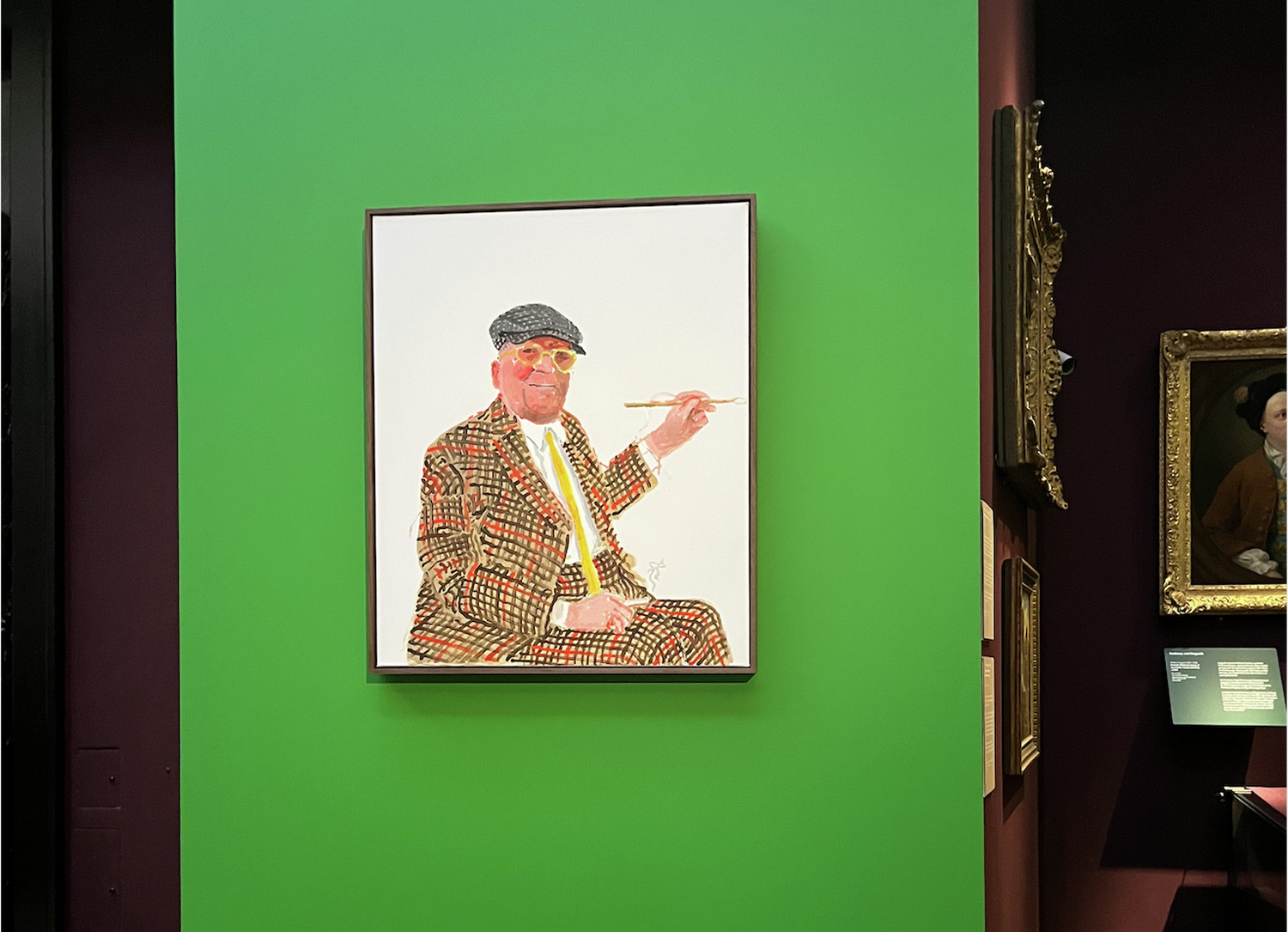

As you walk down Trumpington Street towards the Fitzwilliam Museum, banners of Hockney’s 2021 self portrait border either side of the road, looking down upon you in all his vibrancy. These culminate in two huge banners on the front of the museum, becoming new pillars. Hockney is truly “tak[ing] over Cambridge” (pamphlet), transforming both The Fitzwilliam Museum and The Heong Gallery into his own vivid green, multimedia, iconoclastic trail.

This same self-portrait encapsulates much of what the exhibition aims to do; a presentation of Hockney’s work, yes, but also an examination of art itself, its rules, through the ‘eye’ of Hockney. Hockney’s paintbrush extends beyond the bounds of the painting – taking himself as the starting focus, but drawing our attention out from himself to the pathway of art to come, beyond the illuminated green archway. What remains of the usual display at The Fitzwilliam largely becomes absorbed into the background, the Old Masters the Fitz is known for relegated to examples by which Hockney can argue his theories, or place his own conceptions upon. They are placed in (often literal) opposition to Hockney’s own pieces, as with the staple oil paintings of vases of flowers which now circle around a screen featuring a collection of Hockney’s own drawings of flowers produced on his iPad. Hockney is front and central, commanding our attention.

Throughout, the onlooker is prompted to engage with the art; from a peep-hole containing miniature models positioned directly in front of the painting (Poussin’s ‘Extreme Unction’) which it depicts, or ‘The Perspective Window’ where guests lined up to practise the theory of linear perspective on the very room we stood in, or the large camera obscura outside where children gleefully span the camera in a dizzying view of the bustling street and watched as images blurred when they lifted the plates towards the ceiling. The exhibition is not content with onlookers – it not only wants engagement from you, it demands it.

This creates a lively atmosphere, and on several occasions other guests employed me in their debate, and it was through this discussion that we could turn the artistic processes over ourselves, and come to our understanding through them. This circumnavigates the problem of alienating the visitors who do not have prior understanding of the artistic notions Hockney undercuts or aims to redefine, a problem that is butted against in the ‘Perspective, Orthodox and Reverse’ room, where the central cabinets containing teaching guides on perspective remained hidden beneath cloth, as most visitors refrained from uncovering them, or took a peek and fled.

This physical interaction element does not spill over to the Heong Gallery though; the vibrant green of the Fitzwilliam becomes tape lines on the floor in this gallery, implementing a distance between the onlooker and the art – a more typical gallery experience, perhaps due to its limited size. In contrast to the sheer, sprawling immenseness in the Fitzwilliam, the Heong Gallery is an intimate space. This is not to say that there is also not a creation of a cohesive whole within this gallery as well; Hockney’s voice echoes throughout the space from the 45-minute documentary on show, blending with the visitors' own conversations, to create in the space an animation and energy that mirrors the extraordinary vivacity of his ‘Grand Canyon I’ piece. There are two present paths through the artworks. The first, a focus on Hockney’s career through time, begins with ‘Study Skeleton II’ from his time at the Royal College of Art, and concludes with another screen which has a carousel of his recent iPad drawings. The other path is through the quotations by Hockney that accompany each piece, highlighting his own creative process ideologies.

The description for ‘Grand Canyon Arizona with My Shadow, Oct. 1982’ highlights that “Space is an abiding preoccupation of Hockney’s.” While this is in reference to an interest in depicting space within his art, this also extends off the canvas to influence the creation of these exhibitions. It is really like being within Hockney’s world. The Fitzwilliam explodes with an intensely bright green which is usually only found electronically represented; as the exhibition’s captioning suggests “Hockney goes beyond what can be done with pigments. His astonishing range of greens are made directly from light, emitted not reflected.” While I understand the purpose behind the colour choice and the desire to push the space into the digital world of Hockney’s latest works, it felt overwhelming to be so dominated by it, and also acted to detract from the vibrancy of the works themselves. This extended connection also removed a lot of the individuality of the pieces, denying them the borders of their own canvases, denying us the opportunity to engage fully with them as individual works of art in their own right. Speaking to several members of staff about the colour choice, it appears to be a colour that has to "grow on people".

The ‘Hockney’s Eye’ exhibition truly allows you to step into Hockney’s way of seeing, while also showcasing his immense multi-media range and the creative possibilities that can be explored in modern modes, bringing musings on the process of artistic creation to the forefront of our minds. It is an exhibition fitting to Hockney’s own sprawling experimental career, bringing his career-long obsession with the ‘Art and Technology’ of depiction into a collected whole.