Ask any student how they found working from home during lockdown and you will hear a resounding answer: “challenging”. Amidst the imposed isolation last term, we were forced to struggle without the integral resources which facilitate our degrees. But it would be disingenuous to assume that all students had the same learning experience. As a Humanities student, although frustrated by the physical inaccessibility of critical texts, I still had the luck of library books being scanned for me. What happens when what you most need to fulfil your course is not something easily scannable, but instead expensive tools, tubes of paint, or an expansive studio space? For arts students, these things have been made almost impossible to access over lockdown.

This disparity between subjects led me to speak to five arts students about their experience of producing work from home. Artists have often made a virtue of limitations. Picasso famously said “if I don’t have red, I use blue” and the early abstract expressionists in 1940s New York would experiment with house paints as they were much cheaper - and available in much larger quantities - than expensive artist quality oil paints. Lockdown has certainly been the ultimate test to what one can make with severely reduced resources, and I was keen to find out how it had stretched the creative abilities of these artists.

What happens when what you most need to fulfil your course is not something easily scannable, but instead expensive tools, tubes of paint, or an expansive studio space?

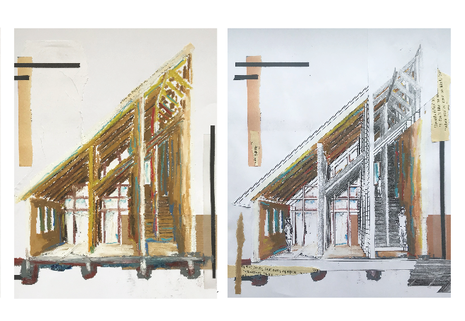

Hannah Back (@archartbyhannah), a second-year architecture student here at Cambridge, argues that there wasn’t that same ability to experiment as freely as before lockdown, when she could easily access the university-provided materials. ’You can’t just quickly order a pack of something. Or if you do, you think ‘I must use it all’ because I’ve spent money. When materials are just there, you can fiddle around with them and suddenly they actually become something.’

Art allows people the freedom to pursue different avenues of curiosity. This is especially true for foundation and first-year students, with their course intentionally structured to teach a carousel of different mediums. These rotations allow for trial and error, playing with materials that may be unfamiliar, but prove fundamental in shaping one’s artistic trajectory. In theory, this is also a period in which students are taught a variety of ‘hands-on’ skills: having inductions on how to use knitting, sewing, printing machines, trying out dye and ceramic workshops, or makeup technique masterclasses. With the pandemic, none of this has really been possible. Inevitably, it has caused a backlash for students. Ella Duncan (@eddy_ded), a foundation year student at Epsom, asked her tutor how much of her University application should constitute foundation year work: ‘She said most of it should be. But at the time, I had been at Epsom for six weeks, and I had only done one piece of art.’

One of the biggest difficulties has been the absence of studio space. Jodie Wagner (@knitme_baby), a first-year student of BA Textile Design at University of the Arts London, emphasised that ‘things start to get messy, so it was difficult to feel free at home. My room is quite small, and so I work downstairs at the dining table, which isn’t huge. I have to eat on it, I have to clear things away, I have to organise my time much more stringently.’ Bedrooms haven’t been conducive to fruitful work for most students, but for artists there is an added problem: they physically need a space to make a mess. As Ella says, ‘A studio is a place where you don’t care what happens to it, you just care about what you make in it.’

It has also been immensely detrimental to lose that valued communal studio space in which artists collectively bounce ideas around, offering criticism and advancing each other’s ideas. ‘Working alongside other creatively focused people is just something you cannot fake at home or over Zoom,’ Ella stresses. ’In a studio you can turn to the person next to you asking, ‘what’s wrong with my painting?’ and they can immediately tell you. It’s a completely inspiring atmosphere.’

However, for Hanna Fee Friedrich (@hannaffriedrich) ‘the biggest problem was coping mentally.’ Hanna is a second-year, studying Hair and Makeup at University of the Arts London. Like most arts degrees it’s an expensive course – having to purchase your entire makeup kit and potentially hair heads too – with an especially uncertain future. Working from home in Berlin last term, Hanna had only a fraction of her kit and no access to hair heads, preventing her from learning and practicing most of her hair unit. Several of her peers felt forced to drop out, a decision that Hanna has even considered herself. ‘Everybody has felt a much higher level of anxiety over the last few months, being scared about what to do with the course,’ Hanna tells me.

Is she worried about the future? ‘Yes, one hundred percent.’ Students pay large sums to learn techniques which necessitate face-to-face contact, so it’s understandable they have had some low moments. ‘I’ve just been exposed to so much less,’ says Architecture student Hannah. ‘I don’t feel nearly as proud of my work currently as I would like and I feel like I’m not as confident in my own skills.’

Certain words crop up across the interviews: ‘lost’, ‘demotivated’, ‘uninspired’, ‘stuck’, ‘concerned’. But what also resonates across the discussions is how inventive they have been during the pandemic. Windows have become lightboxes that can be traced on top of. Colourful plastic bags can be cut up and knit. Putting woodchips on your face is the new editorial makeup look. And all you need for printmaking is some stones, old yarn and paint. Artists have gained a new-found appreciation for their surroundings, and for breathing new life into mundane objects. Each of them has adapted through sheer agility.

‘I end up having all my work spread up on the floor, taped to my windows, hanging on washing-lines across walls,’ said Georgia Smith (@georgias.artt), a first-year student of Graphic Communication and Illustration at Loughborough university. Lockdown was the impetus for Georgia to construct her huge ‘inspiration wall’: a collage of paraphernalia from art exhibitions. On the wall, Georgia often refers to things she likes, materials she could use, thinking of what artists to draw inspiration from – it’s probably been ‘the most helpful thing’ for sparking new ideas. Georgia’s ‘can-do’ attitude is reflected in her shift of work focus. ‘The main switch in my work is that it has become much more humour based,’ she says with a smile. ‘The world is so depressing right now – I don’t want to make anything that’s sad or that isn’t entertaining. Even just using bright colours, patterns, or being more playful with the concepts – I only want to focus on creating happy work.’

Meanwhile, Hanna’s resourcefulness has led her to more sustainable solutions. ‘I got more environmentally friendly. I feel very bad always buying more plastic, but because I didn’t have many materials with me I just started creating my own pigments out of plants. I also started looking more at nature for prompts, creating my own stamps by pressing flowers.’

Financially, creatively, and mentally, lockdown has been taxing for artists, but it has not come without some benefits. Physically producing work from home has shown students’ families their degrees in a new light, now having a greater appreciation for its scope and intensity. Some have even become involved in the creative process. There has also been a vast transformation in how students present their work to tutors, developing new verbal skills to translate their work’s physicality through a PDF file or Zoom call. Architecture relies on a high level of tactility in examining measurements and design, and thus Hannah has learned to ‘construct much more of a narrative, journeying people through the spaces’ of her product. ‘It’s improved the way in which I can speak about my work,’ she says. ‘The tutor receives the work 2-dimensionally through the screen, so I really have to create the 3D picture with my words.’

In light of constraints, arts students have not only developed new modes of communication through which to understand their work, but have been forced to utterly rethink their creative output. Is it not a key component of Art to follow the pace of society’s change, and yet provide new ways of navigating it?

During the first lockdown Hanna was stranded in the countryside with only one lipstick and one concealer to use for all her projects. Cue panic. Now, she tells me: ‘I’ve become such a good problem solver. I’ve been stuck at home for a whole year with minimal materials – I can survive everything.’