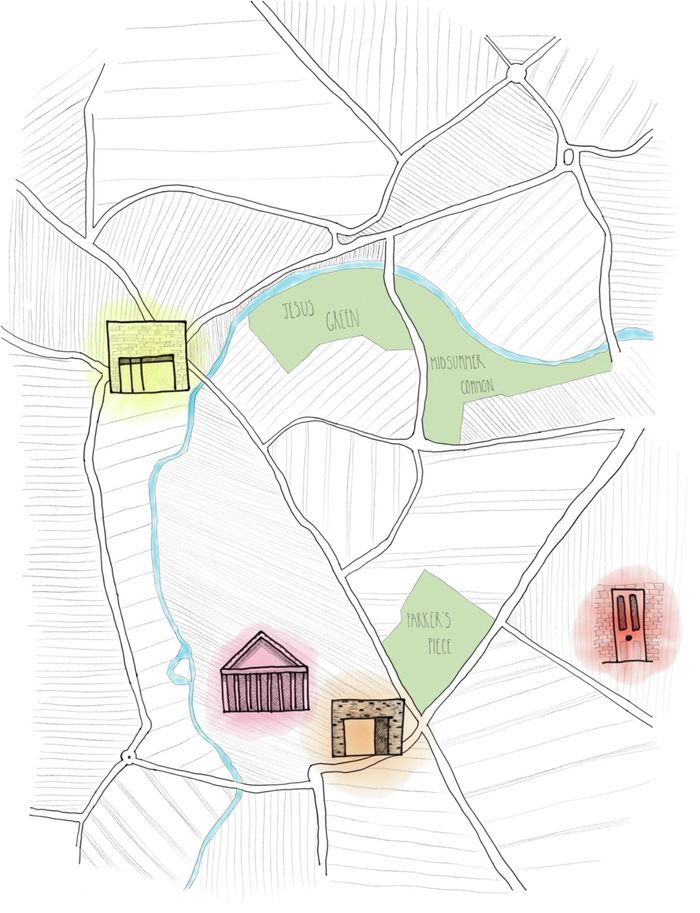

In late June, Paris begins to stir. One by one, museums tentatively reopen, flaunting shiny new rules and systems to tout their neglected galleries: compulsory bookings, masks, enforced one-way routes... The Musée Jacquemart-André is one such museum, attempting to win back tourists and locals alike with its Tate-loaned Turner exhibition.

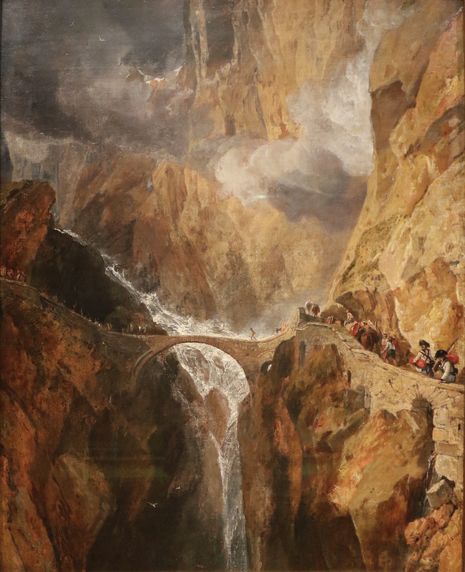

I walk into the Musée Jacquemart-André ready for a strong dose of escapism. After months of home-based lockdown, my objective is momentarily to put aside the worries of the world and focus on something other for a while. Turner’s work does, in a way, constitute a marvellous source of escapist reverie. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was, first and foremost, an inveterate traveller. Motivated by work, never pleasure, the painter traipsed across Great Britain and continental Europe, relying on his phenomenal visual memory and the prismatic depth of aquarelle pigments to transpose light and colour onto canvas.

Turner had a keen sense of the grandiose, both in terms of subject and technique. His vast landscapes, rendered in sweeping brush strokes, draw the observer out of their own limited existence and world view. “Each one of his paintings is a living world that is entirely self-sufficient,” claimed a critic in a 1948 Le Monde article. This statement rings true. Walking around the exhibition, it is not uncommon to spot visitors rocking back and forth on their heels, their sense of gravity off-kilter; they lean forwards as if almost falling into the work itself. Turner’s experimental use of aerial perspective creates an infinite variety of landscapes, or rather of atmospheres. At times unsettling, at others profoundly uplifting – the result is rarely the same, and never dull.

Finally, something to stimulate the senses after months of staring, eyes glazed, at the wall above one’s desk, of committing to memory the same faces, the same conversations, the same neighbourhood walks.

In some of his later, more abstract works, the atmosphere feels impenetrably opaque, almost suffocating. Such is the case with the impressionistic Stormy Sea with Dolphins (c.1835-40), where the viewer floats in a warm, stagnant dreamscape of sulfuric yellows and muddy browns, perhaps a reflection of the painter’s ocular and mental decay as he progressed into old age. In others such as Kilgarren Castle, Pembrokeshire (1798-1799), emphatic convergence lines guide the viewer’s eye about the painting before bringing it to focus on the vanishing point, creating a lasting impression of dynamism and unbridled movement. Clouds are wrenched away; gulfs of light offer a seemingly endless tunnel forward.

Using colour as a vector of light and movement, Turner drags us out of ourselves and into the infinite. Humans are rarely the centre of focus in his work. When he does include them in landscapes, they are minuscule, ghostlike creatures, serving less to tell a story or play a specific role than to ground us in the vastness of nature and underline mankind’s relative insignificance. Inevitably, he tells us, we will be absorbed into the washes of colour that make up our own life’s landscape.

At first glance, this all appears an ideal cathartic experience for the post-lockdown viewer. Finally, something to stimulate the senses after months of staring, eyes glazed, at the wall above one’s desk, of committing to memory the same faces, the same conversations, the same neighbourhood walks. Without leaving the gallery room, the observer has visited France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, has been thrust in and out of space and time – it’s like eye drops for the dried out brain.

However, a problem emerges: it is now difficult for the viewer to experience artwork without drawing parallels or contrasts between the art and our current situation. One oscillates between using art as a form of escapism, a medium by which to distract and forget, and art as an endless source of symbols that echo our current situation. Observing Turner’s paintings, I am constantly reminded, by contrast, of my limited freedom to travel, to take in vast landscapes, to explore the unknown once more. On the other hand, I can’t help but compare our current travel restrictions to those the painter experienced himself – British citizens were barred from continental Europe during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). It’s the same at the Musée d’Orsay: the glassy-eyed subjects of James Tissot’s portraits appear to evoke the malaise induced by prolonged isolation. Comparison seems inevitable, and pushes the question of art’s place and relevance in times of crisis.

Moreover, despite being a considerable privilege, the return to museums, masked, is an unsettling and not altogether victorious one. In a world where social distancing is the new norm, people seem to have acquired a heightened awareness of others’ presences around them. An underlying tension pervades the air, visible in visitors’ nervous shying away whenever another transgresses newly established physical boundaries, and the mechanical shuffle of feet through the arrowed exhibition route. Covid-induced alarm bells ring in my mind as I register that the visitors surrounding me are relatively advanced in years. Why am I putting their lives at risk to gawk at a few drops of paint on a piece of linen? Aren’t they doing the same, voluntarily? In the back of the mind, a nagging sensation lingers – a sense of the overarching non-essentiality of museum-going. Why have we returned to museums? Do we need to?

This question harks back to the philosophical debate concerning art’s fundamental purpose. As Kant underlines in his Critique of Judgement, fine art must be distinguished from craftsmanship in that it lacks a predetermined function; it is, conceptually, useless. When the usefulness or finality of an object teleologically precedes its creation, it can no longer be qualified as art, and instead becomes a work of craftsmanship. In order to justify its necessity, art cannot be viewed as useful; instead, the creation and observation of art must be categorized as belonging to the realm of disinterested leisure, otium. This leisure is essential to mankind. As exemplified in Plato’s Theaetetus, leisure, (here skole) as opposed to productive labour, tears us away from servility and guides us towards freedom. While the dialogue between Thales and his servant focuses primarily on academic skole, more specifically the disinterested pursuit of philosophical knowledge, the thesis can be extended to the realm of art. Conceptually speaking, the creation and observation of art allows us to escape utilitarian instrumentalisation and preserve our humanity.

Why can’t we settle for reading works of literature at home, or simply looking up a painting online?

Although written as a rebuttal of Kant’s work, Hegel’s Aesthetics further upholds the essentiality of art to mankind. The Hegelian thesis posits art as the creation of the soul. To understand or rationalize art history is to interpret it and give it a spiritual meaning; to observe an artwork is to bring oneself closer to the Sublime.

Where do museums come into play, then? Why can’t we settle for reading works of literature at home, or simply looking up a painting online? In the aftermath of the current health crisis, museum-going is surprisingly invaluable, in that it is one of the safest ways of socializing or connecting with a crowd. When looking at an artwork in a museum, you are extending and receiving empathy on three counts: observe an artwork and you are experiencing the perspective of the artist; observe the persons depicted in said artwork and you are engaging with their reality; observe those in the museum around you and you empathize with all those who have observed and interpreted this same artwork.

The connections derived from this experience are virtually infinite. The perspective gained allows one to return home and feel not as though one has escaped from the current situation, but rather that one has transcended it – thus returning to the Hegelian conception of the Sublime. By interacting with art in a museum, you are surrounding yourself with the presence and existence of hundreds of others. Granted, museums are not quite nightclubs. But they are cheaper and safer, and you will wake up feeling a whole lot less worse for wear the next morning.

If both art and museum-going are then vital, which Covid-influenced artistic approach should we adopt? Can we, should we expunge this new tendency to compare and contrast? Following a series of museum visits, I realised that a dual approach is perhaps the wisest. Allow yourself to use the work as a form of escapism if necessary, or on the contrary draw the parallels your mind is itching to draw. Then, applying Kant’s theory of disinterested, pure aesthetic judgement, try to engage with the work of art by taking a step forward and appreciating it in itself, honing in on details and technique: this is the starting point for a new mode of contemplation. While this new mindset might require some adjusting to, it is an important component of the delicate, yet essential balancing act that constitutes our return to museums, masked.