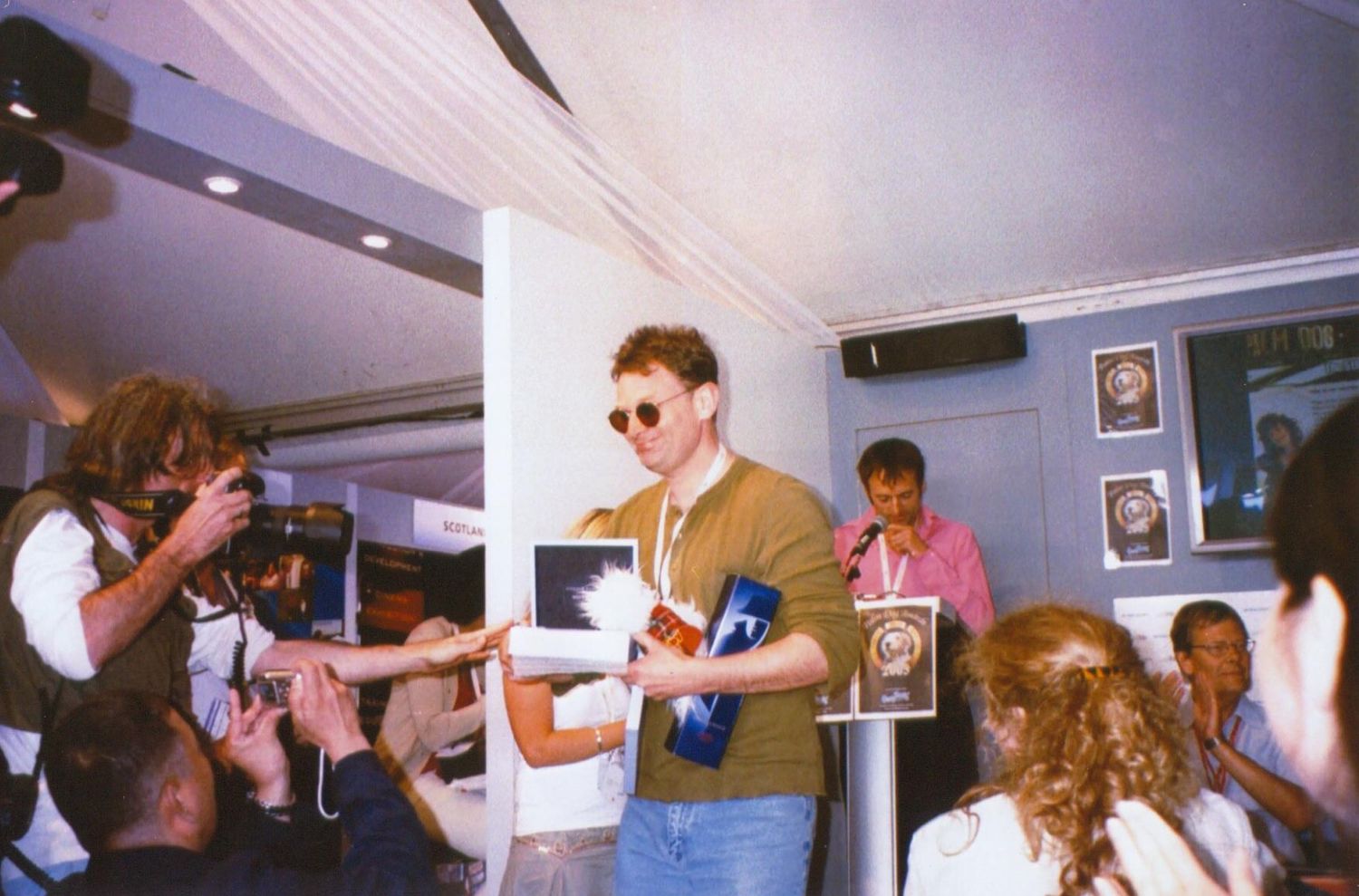

As the Edinburgh Fringe approaches, I interview Ross Smith, a playwright and filmmaker who found both opportunity and experience at the festival. Ross’s recently released book, See You at the Premiere: Life at the Arse End of Showbiz, aims to demystify the apparent glamour surrounding show-business. Brilliantly engaging in its humour and storytelling, the book lures the would-be creative into facing the humdrum realities awaiting them in the arts.

We begin by reminiscing on past interviews, a topic which comes more easily to Ross than to me. “This is my first,” I admit sheepishly. Ross recalls his own first interview—a conversation with director and producer Michael Relph—and how this opportunity was initially suggested by a pal: “My friend Grant said, ‘I’ve just spoken to my dad and he wants you to interview Michael’.” And so it was that Ross’s interviewing career began with the question: “Who the hell’s your dad?”

“The Fringe gives people the chance to really see what they’re made of”

His dad, as it transpired, was Barry Littlechild, Head of the film unit at BBC Radio Two. For the following four years, Ross worked for the BBC, writing programmes, creating documentaries, and undertaking over 300 interviews. “Everything happened because of that one interview,” he reflects: “This is not a science. Anything can happen to any creative person at any single point.”

But alongside this potential, the creative industry involves great uncertainty. Did Ross ever feel settled into his ‘struggling artist’ lifestyle? Or was he always restless? “You never goddamn stop. It affects every aspect of your life. When you look at the media, the only people who get interviewed are [...] generally perceived to be successful. So everyone—the public, and, indeed, aspiring creative people— they think that everyone in the arts is successful because that’s all they ever see.”

Fearful that I might once more make recourse to terms like ‘struggling artist’, I change the subject. Did he ever worry that by adapting his writing to feedback, he was losing his innate style? He gives two answers: on the one hand, it’s good to take practical advice—become more succinct, edit down. But there’s also the content of the writing. “Do you,” Ross asks “write the kind of stories that you want to tell, or what you think the public wants, or what the industry wants, or what the market wants?” His own answer is clear from the number of expletives thrown at the public, the industry, and, indeed, the market: “It’s you. You’re the artist, you’re the voice, you’re the one that’s decided [...] they want to tell a particular story. You have to be true to yourself. Because, if you do, you’ll want to get up every morning and work on that project.”

“Comedy more than any other genre is usually a product of its time”

What about current trends in comedy? Shows like Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag? Do they reflect a movement towards more personal storytelling? “Hell yes! Back in the day, stand-up comedians were gag-smiths. They had writers who wrote their material and, once told, those jokes were taken by any other comedian who wanted to use them. And then what happened in the early 80s, when alternative comedy came along—you’re talking people like Alexei Sayle, French & Saunders—they said: ‘We want to do personal stories. Comedy is almost being wasted just making people laugh.’”

He tells me that there are two types of writers—those who see the world as it is and those who see it as they want it to be. Which is he? “Ah, gee whiz! I’ve got a big mouth, but when it comes to backing it up… ‘As you’d like it to be’. I’ve noticed my work seems to centre on ‘struggle-against-the-odds’ narratives. Greyfriars Bobby, One Small Step, The Wright Brothers and a current theatre project I’m working on are all about the underdog pulling through.”

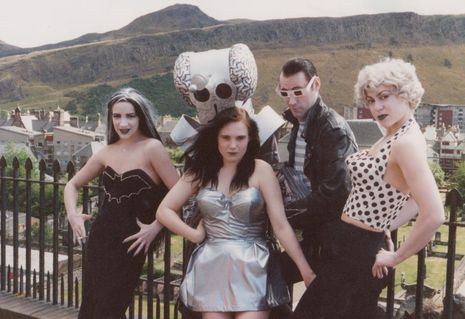

After a digression into our respective affections for Greyfriars Bobby, we move to another of Edinburgh’s cultural bastions: the annual Fringe. Ross has brought three shows to the Fringe. One of these, One Small Step, produced by Oxford Playhouse, went on to tour the UK and became the world’s most-toured British play of 2010 when it was performed in 22 countries.

“[Edinburgh] gives people the chance to really see what they’re made of. It disciplines you, and it makes you realise: ‘Do I really want to do this for a living?’ This year we’ve got Ian McKellen playing Hamlet. Ian McKellen doesn’t need to play the Edinburgh festival, but he’s doing it for the experience. That’s what you’re going to get when you take a show [to] Edinburgh. You get a life experience. Everyone really should [go], if they want to be in the arts. It’s a rite of passage.”

We go on to discuss pen names—aspirations of sounding like a working-class hero, realities of sounding like an SAS fanatic, and an underlying desire for hermitage—before concluding with a most poetic of interview endings: an ode to the immortality of the artist. In his book, Ross describes the permanence of art. But is this true of comedy, notorious for its cultural specificity?

“Comedy more than any other genre is usually a product of its time. But what I meant was: the work itself, that will live forever. Someone in their silver space suit walking into—well you wouldn’t walk into the British Library in 300 years, it will be something you get beamed into your brain—[they can] search for See You at the Premiere and it will tell you about what it was like [...] for a lot of artists in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. And you will learn about Soho back in 1995, when young filmmakers were popping up all over the place, you’ll learn about going to the Edinburgh Fringe, you’ll learn about going to the Cannes Film Festival.

“If you create art, you are able to communicate with people a week from now, a year from now, a century from now, a millennium from now. If you deliver now, you will find immortality.”