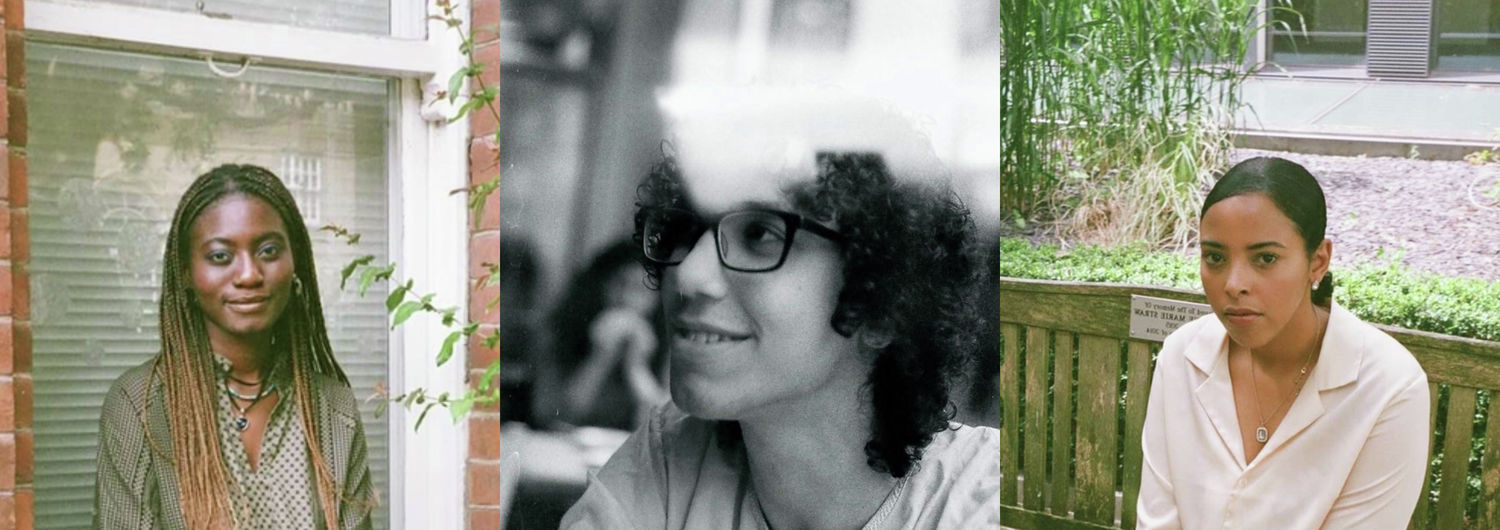

Vidya Divakaran, President of Bread - Cambridge’s theatre group dedicated to supporting minority narratives and creatives - led the following group discussion last term as part of a Writing Workshop. She interviewed three of Cambridge’s most exciting student playwrights of colour on their work, top tips, and the importance of identity when writing. Vidya interviewed the following three playwrights:

Mojola Akinyemi (English at Jesus) - writer of the acclaimed Great Mother, Iya Ayaba, meant to be performed at Vault 2022 before the festival’s cancellation due to the omicron variant

Abraham Alsalihi (Medicine at Magdalene) - writer of The Calligrapher, the CUADC Fringe show to be brought to the Corpus Playroom in Lent

Chakira Alin, (English at Queens’)- writer of Heroes, winner of the Marlowe Other Prize and the Mustapha Matura Award

Vidya: So, what did you write and why?

Abraham: I wrote The Calligrapher which is a play about a Quran that Saddam Hussein had written in his own blood. And it’s a controversial issue because on one hand, you can’t write a Quran in blood, because blood is filthy. But on the other hand, you can’t destroy it either. And I thought that that was a really good allegory for the historical impact that a lot of Western intervention has had on the Middle East, and for how the artefacts of those events have carried through till today.

Chakira: I’ve written a play called Heroes about a young man from a council estate who has never known his father. One day he meets him and his world is rocked within 24 hours. I was exploring issues that are often faced in these areas, like knife crime. It’s about the area I grew up in, my hometown, East London, and coming from a family of refugees.

Mojola: So, I wrote a play called Great Mother, Aya Iyaba. It’s set in Nigeria in the late 60s and early 70s following the events of the Biafran war - that was a civil war that happened in Nigeria post independence from being a colonial state of Britain. It’s a play that follows a young nun, who is starting at a convent, called Agnes. I lived for a long time over lockdown with my cousins who grew up in Nigeria, and it was really insightful: I got this cultural education that I just was really missing.

“I wanted to respect these people, represent them. I thought, should I even be doing this? But it’s also my history as well”

Vidya: Importantly, for all of your plays, your main characters aren’t you - in that, they are characters with vastly different lives to your own. So how do you go about researching someone else’s character so you can make it authentic?

Abraham: So for me, it started with researching the history of the blood Quran. But I very quickly found out that no one knows very much. And the guy who wrote it - no one really knows anything about him other than he lives in Virginia.

Vidya: Do you ever want the person who wrote the real-life blood Quran to know that you wrote a play about him?

Abraham: To be honest, I kind of would, I would love for him to watch it and go, ‘Actually, that’s complete rubbish. I loved writing the book. I tell everyone about it every day!’ I’d love to see what he thinks of it.

Chakira: Yeah, with my play - Heroes - the main characters in the play are all men. I spoke to my dad a lot. So I would ask him all these questions about his father, and football. Also I noted things down. I talked to my cousins too, not letting them know it was for a play, just kind of mining their thoughts. So they actually are entitled to half the copyright of my play!

Vidya: How long did it take to write?

Chakira: I’m embarrassed to say, but I wrote most of it in three days -

Everyone: What?

Chakira: Because, well, I wrote it specifically for The Other Prize, which had the same deadline as a different piece of work that was due. So I wrote the bulk of it in one night, if I’m being honest with you - it was very raw, literally just my first thoughts unfiltered.

Mojola: Stunned. So my process: I’m a very visual thinker, my first initial thoughts were of the scene of a woman dressed in pink on the floor, and then the opening scene, and then women leaning over the ledge- these are all key moments in the final play. And I also used the Biafran War Memories website in my process - but it almost felt insulting. I was reading the stories about people who lived through harrowing things, and there I was taking them for my play. It was a weird dynamic, where I wanted to respect these people, represent them. I thought, should I even be doing this? But it’s also my history as well. And I tussled with this a lot.

“A lot of the time when people talk about the Middle East, it’s sort of this ‘other’ place”

Vidya: Another question for everyone, what impact does your identity and lived experience have on the narrative and its intentions?

Abraham: I think that a lot of the time when people talk about the Middle East, it’s sort of this ‘other’ place. Whereas, I was born there, my family is from there, so I wouldn’t say I have a better understanding, but I have such a different understanding of what life in the Middle East is like.

Vidya: So in your play, there’s Haytham, who’s quite pro Saddam Hussein, and then there’s his son, who has a more American upbringing. How does your attitude compare to that of your two characters?

Abraham: Whenever anyone reads the script, they assume that I identify with the son. Whereas actually, I resonate more strongly with Haytham, the father, who cares very deeply about his nation. Because that’s just the attitude that I grew up around. I think he- the father- represents more than just me- he represents my family and people of my parents’ generations. Whereas Ahmed- the son-, who’s a bit more progressive, maybe represents Western attitudes a little bit more.

Chakira: Yeah, my identity had a massive impact on me when I wrote this play. Whenever I come home from uni, I always experience this massive culture clash. I’m from Newham, which is, I guess, the most deprived borough in London. And coming from doing my English degree to a place where I’ve got four different languages floating around at home. . . It’s such a different world. I was influenced by immigrants growing up. One of my main characters is a Palestinian boy. I’d never read a play with a Palestinian person in it before. I live with my grandma - she’s a refugee, and talking to her made me want to write about this immigrant community. So everyone in my play is an immigrant; even the white people, they’re all from Ireland or Poland. No one’s really English. So the play is also about national identity and how Britishness relates to that.

Next week: the interview continues with thoughts on the writing process, advice for student playwrights, and why more students of colour should write plays