The austerity of Samuel Beckett’s writing means that it can be performed anywhere. Beckett would start writing with a specific place in mind before draining the play of any signifier of time or space; they’re often set against a black void, though directors haves taken Beckett into the moment – Waiting for Godot was staged on the streets of New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in November 2007. King’s Drama Society has taken a collection of Beckett’s play for one night into the nave of the college chapel. The result: a gloomy, handsome though uneven performance framed by natural darkness.

The nave of the chapel is an intricately beautiful space – Wordsworth described ‘These lofty pillars, spread that branching roof Self-poised, and scooped into ten thousand cells, Where light and shade repose’ – a far cry from Beckett’s typical ‘bare stage’. Yet performing the Shorts here is a masterstroke. Beckett’s spaces are dark, and the 16th century chapel can become pitch black; when its staccato, shuddering flood lights are switched off the darkness is more profound than any theatre in Cambridge. It is also true that while staging the collection in a traditional location like the Corpus Playroom would have given the collection an intimacy, it would also have been too normal: the actors more clearly actors, the audience more overtly ‘there’. The abstract plainness of the collection soars in an enormous, inhuman space.

“This was a thoughtful selection, complementary and contrasting”

There is also something about the beauty of the space that seems to fit with Beckett – while Wordsworth captures the detail, as a whole space the beauty of the chapel truly escapes words. Beckett himself wrestled against the constraints of language, though his focus was not artistic beauty but the human struggle. Performing these plays at this chapel instantly gave it a subtle majesty, a wordless potency which shrewdly frames the thematic air of the production.

The selection of plays was performed twice on 12th November – the first at 7:30 followed by a second showing at 9. As late Beckett plays, the three share a bleak simplicity and an exactness of structure down to the lifting of a head or the crack of a knuckle tap. Where they varied was in tone, form, and crucially their basis in reality, becoming more unsettling with each play. Joined together by an awful scuttling sound every time the lights went down, this was a thoughtful selection, complementary and framing each other.

The first play ‘Catastrophe’ is Beckett’s most political and therefore accessible play. A director and an assistant director adjust a third, silent character on a pedestal, gradually making him a symbol of the oppressed. The latter is made to shiver and stand in an uncomfortable stance until the last moment where he reclaims independence of action, thereby illustrating how the victim is not passive. The acting here was serviceable, though because it was staged to the right and contained a lot of activity, the dialogue was too often lost in the cavernous space. The relationship between the director and their assistant is one of complicity and oppression though this subtlety was hard to read at a distance. Also unfortunate was the use of a weak phone as a spotlight – the all-important final lift of a head was swallowed by the darkness – I’m not sure the scattered audience noticed it.

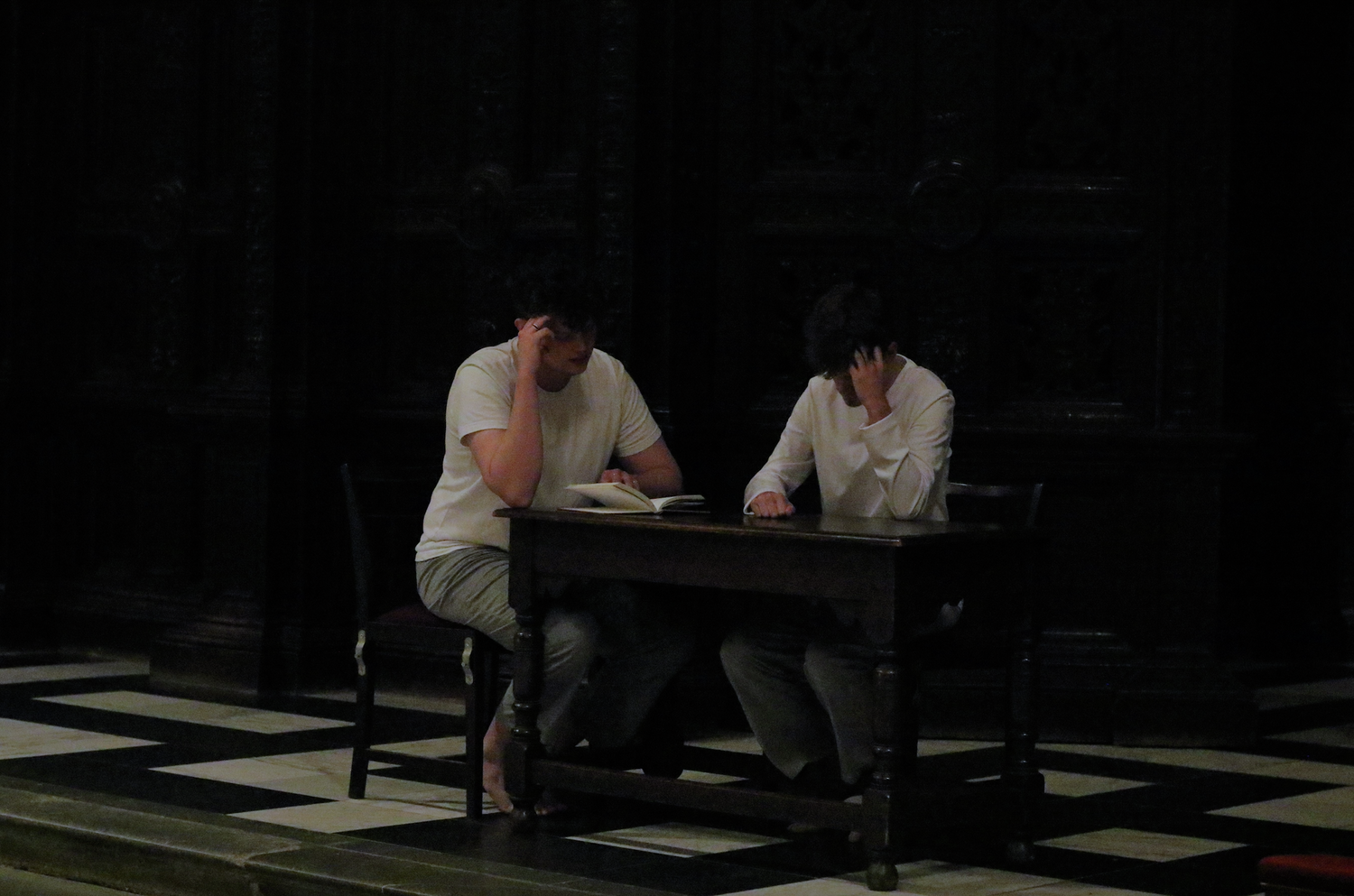

The second play was ‘Ohio Impromtu’. Two identical figures sit at a desk. One reads a story to his mute companion, who interrupts several times with a knock on the desk signalling to reread a line. The story told by the reader is of another pair, a widow suffering on an island whose only comfort is a night-time visitor reading him a story. The King’s performance was slow - the reader articulating clearly but without tonal expression, almost as if he was bored of his role here. Other performances of ‘Ohio Impromtu’ have emphasised the bedtime story-like nature of the reading though I enjoyed how eery this version was, well suited to the gloom in the centre stage. In this tired reading though the obvious contrast between the two sets of pairs was lost - there was no comfort on stage. Slow too was the knock with the listeners arm creaking up before cracking the desk. A simple vignette, the acting here was subtle and dutifully in line with Beckett’s famous advice not to act. Eerie, unsettling and well-paced this would have been the highlight if not for the final play.

“This version was well suited to the gloom in the centre stage”

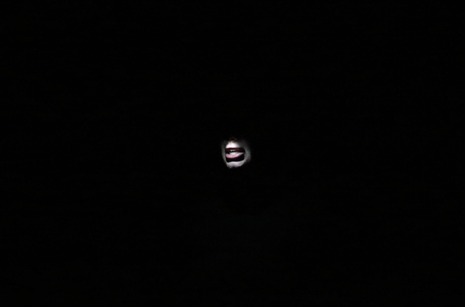

‘Not I’ is Beckett’s most difficult play and as such a bold choice. A single 15-minute monologue performed by a mouth lit solely in pitch black. A woman, performed here by Maia von Malaisé recounts her experience of a trauma which has left her mute and a buzzing in her head. The monologue is an outburst, the speaker interrupts herself, has ticks and screams, spinning in and out of a story. The script itself reads like the Penelope episode of Ulysses – perhaps Beckett’s major influence here – putting into words thoughts:

MOUTH: . . . . out . . . into this world . . . this world . . . tiny little thing . . . before its time . . . in a godfor– . . . what? . . girl? . . yes . . . tiny little girl . . . into this . . . out into this.

As Mouth Malaisé gave one of the most breath-taking performance I’ve seen in Cambridge – the articulation of every word piercing the overbearing silence. A fast paced performance without mistake might easily have seemed over-rehearsed. To Malaisé’s enormous credit it still felt soulful, realistically evocative of an unnamed, terrifying trauma - the humanity spilled out. Every word too was weighed into its syllables giving the whole monologue a striking, rhythmic purpose. Spell binding.

With the final splutter to black the audience was left in silence. This wasn’t a mournful or reflective quiet, more a confused tension – had it ended? The lights eventually came back, the doors were opened, and we were shown outside. Was this ending on purpose? A resistance to the norms of theatre in line with Beckett? Or unintentional, an unfortunate result of staging modernist work and an unresponsive lighting system which meant that the cues to the audience that it was over were lost. I like to think the former, that quite simply there was ‘Nothing if left to tell’. The audience would decide when to leave.

Staging Beckett is difficult – he leaves such specific stage directions - almost mathematical - that coordinating it on stage is challenging, let alone giving it meaning. The Kings drama society has done a fantastic job here. This is a grim collection, as much about darkness and silence as it is about the intricate vignettes. Much of this was to do with the space, and while it meant some of the nuance had to be sacrificed, it was a courageous move which paid off. Uneven yes, this was a handsome and often poignant celebration of Beckett.