Laurence Blair had just returned from 18 months working as a journalist in South America. For all of its charms, the desk-bound job in Canary Wharf felt a little tame in comparison.

“I had to commute in from North London every morning for nine, nine-thirty, ten am – I pushed the boundaries there a little bit. I’d get the Northern Line down to Bank, and then the DLR from Bank to Canary Wharf station.”

Despite the mundanity of the routine, there is one morning in late January 2016 that Blair can still recount today. “I remember being sat at the front of the DLR carriage; it pulls out of Bank, and you can see Canary Wharf in the distance, all the big financial towers and gleaming spires, and the old docks of East London. You pull into Canary Wharf and it feels like you’re pulling into this kind of financial Disney World.”

“I remember getting a message from Paz Zarate, who was also at Oxford Analytica and was a mutual friend of ours, and she said, well: ‘Giulio’s gone missing.’”

“You try to rationalise and hope for the best. You think, well, there must be an explanation for this, or as long as the outcry is big enough, assuming he’s been taken, or pulled in by mistake, or as soon as that mistake is rectified, maybe he’ll be fine.”

“To an extent I tried not to worry about it too much, tried to reassure Paz; I said ‘I’m sure things will turn out okay,’ because you don’t think that this sort of thing could happen, especially when you’re thousands of miles way away pulling up to the City of London in your suit. The idea that a friend who you worked with in a similar office a year or two previously could be abducted and murdered doesn’t really occur to you.

“It feels like something out of a nightmare, really.”

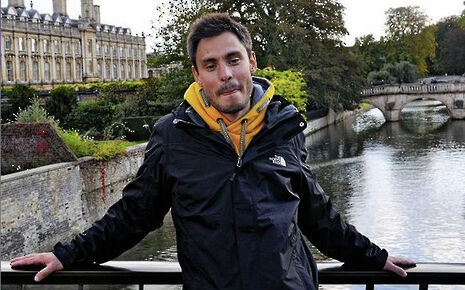

Blair had become close to Giulio Regeni while both worked at the consultancy firm Oxford Analytica, and remembers him fondly as someone always willing to have a chat, whether that be in the office or the pub. Their friendship continued even after both left the firm: “We’d trade a bit of news about work, talk about personal lives, what we were up to, girlfriends, whatever. That was good. It felt nice to have someone a few years older than me who had managed to create a career similar to what I wanted for myself.”

“There’s a tendency for people who become international relations scholars to go down this very dry route, where they sort of become talking heads and without any commitment or attachment to the society they cover.

“So for me it was really encouraging to see someone who focused on a different part of the world, one with its own characters and problems and opportunities and challenges, like the Middle East. I thought I’d like to do something similar for Latin America: write, research, travel, be able to combine a career in academia or writing without losing sight of the values which we held in common: democracy, a fairer society, freedom of speech, human rights.

“These are things he was very much about. He was an inspiring figure.”

Regeni had left Oxford Analytica to start work on his PhD at Cambridge, looking into the independent trade union movement in Egypt. It was while doing research in Cairo in early 2016 that he was abducted, tortured, and murdered. Over two years since his body was found, nobody has been charged with his murder.

“It’s one of those things you perhaps don’t understand until you’ve had someone murdered in this way is how it feels not to have justice served,” continues Blair.

“That sense that those who are responsible are still walking the streets, sitting in government offices, enjoying their position at the top of Egyptian society, kept in their place by oppression. I do feel a real anger and a real desire to have movement in the case, to see justice done.”

Blair’s frustration is shared by many, from Regeni’s friends and family to anyone who cares about human rights. It seems scarcely believable that a crime like this could take place, let alone go unanswered for two years: an Italian citizen, a student at a leading British university, callously murdered in Egypt.

Therein lies the part of the answer. For the murder of Giulio Regeni was very much a globalised one: he was able to travel from one country to another, and pursue his research interests in a different part of the world. Yet this transience, this connection to so many institutions and organisations, has meant no one group has stepped up and taken responsibility. The story of the murder of Giulio Regeni is not just the story of a murdered PhD student; it is the story of accountability being passed from one body to another, of a responsibility blame game.

Disappearance

The last time anyone heard from Giulio Regeni was 7:41pm on the 25th January 2016. Though it was the five year anniversary of the uprising which toppled president Hosni Mubarak, there is no indication Regeni felt any particular trepidation as he made his way to a cafe near Tahrir Square to celebrate the birthday of a friend, texting his girlfriend to say “I’m going out”.

His body, naked from the waist down, was found by the side of the Alexandria Desert Highway nine days later. An Italian autopsy later found that he had been tortured for four days, though it would have been obvious to anyone who saw the body. Some teeth were missing, while others were chipped and broken. His body was covered in cigarette burns. His right earlobe had been sliced off.

In the immediate aftermath of the disappearance, the Egyptian government struggled to find a coherent position. In early meetings with the Italian ambassador to Egypt, the foreign minister, interior minister, and national security advisor all claimed to know nothing about Regeni or his disappearance.

After the discovery of the body, the interior minister moved quickly to deny any involvement of the state security forces. Instead, the chief Egyptian investigator suggested that Regeni had been killed in a road accident, a claim which fell apart after the evidence that he had been tortured became public knowledge. Meanwhile, rumours started to spread. Regeni was accused variously of being a drug addict, of being gay and having been murdered by a jealous partner, and even of being a spy.

Over the coming weeks, international suspicion towards the Egyptian state grew. One of the chief investigators, Major General Khaled Shalaby, had previously been convicted of kidnapping and torture. The US claimed to have acquired intelligence proving it was Egyptian security forces who had tortured and murdered Regeni, though they did not disclose which precise agency was involved through fear of exposing their source.

At the same time, Italian investigators who had gone to Cairo were finding their work constantly obstructed. They were allowed to interview witnesses only briefly, with Egyptian police still in the room. CCTV footage from the subway station near Regeni’s apartment had been deleted, and access to his mobile phone metadata was denied.

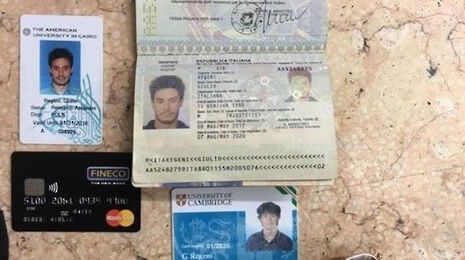

On the 24th March, Egyptian police claimed to have made a crucial breakthrough. Finding a minivan being driven by a gang they said were petty criminals with a history of drug abuse, the police shot dead all five men inside. State media reported the group had been a gang of kidnappers, which had been targeting foreigners and were responsible for Giulio’s murder. A raid on a linked apartment had apparently thrown up Regeni’s passport, credit card, and Camcard.

Yet Italian investigators were able to easily and quickly use phone records to show that the gang leader had in fact been 60 miles north of Cairo on the day that Regeni disappeared. Witnesses to the shooting of the gang said that it had been done in cold blood, with one member’s body repositioned as he had tried to run away. The story soon collapsed, raising at the same time the question of how the Egyptian investigators had managed to acquire Regeni’s passport and credit card.

Real progress came later in the year, when in September Egypt’s chief prosecutor, Nabil Sadek, admitted that the country’s National Security Agency (NSA) had been monitoring Regeni prior his death, believing that he may have been a spy. Around that time, Italian investigators discovered that the policeman who had ‘found’ Regeni’s passport had been in contact with the NSA team following him.

Since then, things have slowed somewhat. In September 2017 a lawyer representing the Regeni family was arrested while en route to Geneva to speak to a UN working group on forced disappearances. He later appeared in court on charges of “managing an illegal group, spreading false news … [and] cooperating with foreign organisations”. While in detention, Ibrahim Metwaly Hegazy said that he was electrocuted and kept in solitary confinement.

Closer to home, Maha Abdelrahman, Regeni’s supervisor, had her computer and mobile phone seized by investigators in January 2018. She was also questioned by British police on behalf of Italian magistrates after Boris Johnson, the foreign secretary, gave permission for her to be interviewed. A source close to Abdelrahman said that she gave the same answers that she had given when she was first interviewed by police in February 2016.

As thousands gathered in Cambridge, London, and across Italy to commemorate the two year anniversary of Giulio’s death, there were then still far more questions about what happened to Giulio than there were answers.

The Italian (hatchet) job

The debate surrounding progress in the case – or lack thereof – has led onto questions of who is to blame, and as is a common theme in this story, different parties give different answers.

For most, including Amnesty International, the answer is clear: the Egyptian state were responsible for the murder of Regeni, and it is in Egypt that the perpetrators will be found and brought to justice. It was this belief that motivated a small protest outside of the Egyptian Embassy in Mayfair on a bitterly cold morning in early February, the day before the two-year anniversary of the discovery of Regeni’s body.

“The Egyptian state murdered Giulio, I am in no doubt about that.”

Daniel Zeichner MP

Organised by Amnesty, though with representatives from the University and College Union, CUSU, and Italian students from London universities also in attendance, the event saw the delivery of 800 letters demanding that the Egyptian government do more to bring Regeni’s killers to justice. As the rally finished with chants of “Egypt, shame on you / Truth for Giulio”, the takeaway message left little to the imagination.

It’s a message taken up by Cambridge’s MP, Daniel Zeichner, when I speak to him on the phone. Despite emphasising the questions he’s asked in Parliament, debates requested, and European colleagues he’s met with, Zeichner is in little doubt as to where responsibility lies: “In the end, Giulio was brutally murdered in Egypt, pretty clearly by one part of the state’s apparatus, and that’s where responsibility must lie with this.”

“The Egyptian state murdered Giulio, I am in no doubt about that.”

But while seeing the Egyptian authorities as responsible for both the killing and the investigation, Zeichner also thinks the British government should be doing more to press the case. Nothing that we have learned in the two years since Giulio’s death, he argues, have come about through the actions of the UK government.

“I think quite a few observers in all this would say that both the Italians and the UK government’s attitude to the Egyptian regime has been at best ambivalent; I think we need to be far more critical of the Egyptian regime than we have been.”

And then there are those who point to Cambridge. For some Italian politicians, academics, and sections of the press, the University is at least partly culpable for what happened to Giulio, and has not being doing enough to assist in the investigation.

On the 2nd November 2017, the Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica published an article with the headline ‘Regeni, Cambridge lies’. The piece was quietly sensational, implying that the University of Cambridge was in part culpable for the disappearance, torture, and murder of Regeni.

“If it is true that everything ended in Cairo, and his torturers and assassins continue to enjoy protection under the el-Sisi regime,” the piece read, “then it is also true that everything started five thousand kilometres away to the north.” It claimed that Regeni’s Cambridge supervisor, Dr Maha Abdelrahman, was refusing to answer crucial questions about the case, and had even taken a sabbatical in order to avoid appearing at the inquest into the murder.

Significantly, La Repubblica said they had seen a ‘European Investigation Order’, which shed light on the relationship between Regeni and Abdelrahman. It contained transcripts from two Skype conversations between Regeni and his mother, Paola.

In the conversations, La Repubblica claimed Regeni expressed discomfort with the topic of his PhD, the independent trade union movement in Egypt, and the choice of his supervisor in Cairo. It was Abdelrahman – according to this description of events – who made him study that topic, and encouraged him to develop close relationships with trade unionists, despite knowing that it could be dangerous. Regeni, La Repubblica wrote, “endured her choices”.

The Italian deputy minister for foreign affairs slammed the University for a lack of cooperation with the investigation. “Shame on you Cambridge Uni,” he wrote in a tweet.

The article was quickly condemned, with 334 academics – including 32 from Cambridge – writing to The Guardian to call the allegations “malicious and unfounded”, explaining that the supervision system did not work in the way La Repubblica had implied. But their intervention did little to settle the case. Though the November article was the most provocative articulation of this line of thinking, it was not the first time Cambridge had been blamed.

Instead, it formed part of a long-running series of accusations against the University that might have intensified as the case has dragged on, but started only months after Regeni’s body was discovered in February 2016.

In the June of that year, Italian deputy minister for foreign affairs Mario Giro slammed the University for a lack of cooperation with the investigation. “Shame on you Cambridge Uni,” he wrote in a tweet. “You value more your ‘secret researches’ than a human life.”

The charge was echoed two months later by the Italian prime minister, Matteo Renzi, who said the University’s “silence” on the issue was “inexplicable”. It was a theme Renzi would return to over a year later in November 2017, when he said that those who worked with Regeni prior to his death “could be hiding something”.

Adding to the criticism from abroad, an Italian professor at Oxford, Federico Varese, told La Repubblica that Cambridge bore “moral responsibility” for not having done more to protect Giulio and that the University’s “priority is only to protect Cambridge from possible legal responsibility and a request for damages”.

La Repubblica itself responded to the criticism of its original article, publishing a piece on the 4th December with the headline ’La Repubblica responds to Cambridge: Our commitment to find the truth’. While reaffirming their belief that the Egyptian authorities are ultimately responsible for Giulio’s murder, the paper doubled down on its claim that Cambridge has questions to answer.

Since then, it has also been claimed that the University has been obstructing the investigative process. Abdelrahman is said to have avoided meetings with the police, while the University is accused of being more interested in protecting its own image than properly scrutinising the decisions and events that led up to Giulio’s death.

International blame game

It is perhaps easier for journalists and former politicians to be more bellicose in their criticism of the University than it is for those who are still serving. Isabella de Monte, the MEP for Regeni’s home region in Italy, certainly chooses her words carefully when I speak to her on a visit to Cambridge: “I think there’s a lack of a good image of the University of Cambridge. In Italy people believe what they read in the newspapers, that there is not much cooperation between the University and Italian authorities.”

“I think the University now has the inclination to cooperate. But there is a different system of law [in the UK], they have to be prudent, they cannot explain everything. This is maybe why in Italy they think they [the University] doesn’t want to cooperate. Sometimes there are reasons why they cannot.”

The claims drew an unusually outspoken riposte from the University (who declined to put forward anyone to interview for this piece). Vice-chancellor Stephen Toope – a man whose job is essentially defined by guardedness and circumspection – in a statement released on the 16th January called the accusations “inaccurate, damaging and potentially dangerous”.

“It stems from a fundamental misapprehension about the nature of academic research. It demonstrates a lack of understanding of scholarly aims and methods. It shows a failure to understand the intellectual relationship between a PhD student and his or her supervisor,” the statement continued.

Some British politicians have refuted the accusations in just as strong terms, with Daniel Zeichner calling them “very, very unfair”.

“I see no evidence to support some of these claims. They are just conjecture as far as I can see, and they do seem to be diverting responsibility away from where responsibility must ultimately lie, which is in Egypt.”

One would be forgiven for thinking that this is a case of one country trying to shift the blame for the crime, and responsibility for the investigation, onto the other. But these claims do not fall entirely along national lines. Antonio Marchesi, chairperson of Amnesty International Italy, says they have “no evidence that Cambridge University or any of its staff is withholding useful information or not doing enough”.

Indeed, “the frequent references in some Italian media to ‘la pista di Cambridge’ (‘the Cambridge track’) could in fact send the (wrong) message that the truth about Giulio’s death is not to be looked for primarily in Egypt, which is where he was tortured and killed in the context of widespread violations of human rights, but somewhere else; and, yes, there is a risk that the search for an ‘alternative’ explanation of what happened may be instrumental to (and result in) reducing pressure on the Egyptian authorities”.

Having known Giulio, Laurence Blair is disbelieving of the La Repubblica version of events. “Giulio was an experienced researcher, he spoke Arabic fluently, he had experience in the Middle East. He chose his topic freely and fully. This was a topic he was interested in, a topic he was equipped to study in, there was nothing out of the ordinary. Trade unions is an accepted topic of study in any country, and in Egypt particularly.”

“The way we see it, speaking for myself as a friend of Giulio and others of his friends, is that there’s an attempt by the Italian police to shift the focus onto Cambridge, and ultimately that’s an attempt to divide Giulio’s friends and family, to divide what should be a united front between Cambridge, between the UK government, between Giulio’s family, his friends, to actually work well together.”

The accusations coming from some in Italy could be put down to frustration. Two years on, with the full truth still to come out and no one being found guilty, it is perhaps understandable that people are trying to find any way of moving the investigation on. Yet as Blair implies, there are those who think the Italians have far more dubious motives for putting the blame on Cambridge.

Italy is Egypt’s biggest trading partner in Europe, with longstanding commercial and diplomatic ties. In August 2017 Italy returned its ambassador to Cairo in an attempt to normalise relations, a move that was sharply criticised by Giulio’s family. When it has been two years and very little has come out, it is easier, some argue, for the Italians to blame Cambridge than it is to ramp up the pressure on Egypt and put at risk potentially lucrative connections.

“The Italians quite clearly have some pretty big financial and economic interests, and my observation would be that that has rather coloured their approach in this whole affair as well.”

Daniel Zeichner MP

Shortly before Giulio arrived in Egypt, the Italian state-controlled energy company Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi – a company that in 2014 Renzi called “a fundamental piece of our energy policy, our foreign policy and our intelligence policy” – discovered an estimated 850 billion cubic metres of gas 120 kilometres off the north coast of Egypt. An official told the New York Times that diplomats in the Italian foreign office thought that ENI were working together with the Italian intelligence service to bring the case to a close.

Italy’s move to return its ambassador to Cairo, drew criticism from Regeni’s family. After a meeting with Italian ministers in the November of the same year, the Egyptian minister for industry and foreign trade, Tarek Kabil, said that trade between the two countries “is targeted to reach an annual level of €6 billion, up from a current value of €2.59 billion”.

Going forward, Italy would be investing a further $2.7 billion in tourism, agriculture, and industry, among other fields, Kabil said.

While it is difficult to prove causation, there is a sense among some that the Italian approach may be being unduly influenced. “I think that a dispassionate observer would find it hard not to come to that conclusion,” says Daniel Zeichner. “The Italians quite clearly have some pretty big financial and economic interests, and my observation would be that that has rather coloured their approach in this whole affair as well. And my feeling in recent times has been that the Italian government has tried to deflect responsibility onto the University of Cambridge.”

Cambridge’s campaign for truth

Regardless of their exact motives, the broad consensus seems to be that the accusations from La Repubblica and co are off the mark, and run the risk of turning attention away from the investigation in Egypt. Yet the claims continued to have been made throughout the two years since Giulio’s murder, and have been able to stick. Even if it has not obstructed the investigation in any way, could the University have done more to help? How was such an idea allowed to come about? And – two years on – do people in Cambridge still care?

There is a case that in the immediate aftermath of the killing, the University was unsure how to act, and as a result did not do nearly enough to speak out, potentially missing its window of opportunity to force the issue. Laura Bates, chair of the University Amnesty International group, thinks so.

“The University itself, because it’s involved in the investigation, has been quite reticent in engaging with the more political aspect of it, though it is really difficult. At first among the student group I think there was some sense of anger that we needed to be doing more.”

Bates stresses that she understands the sensitivity of the case for Cambridge. There are still plenty of postgraduate students studying in Egypt, she says, whose wellbeing the University does not want to put at risk, and one should not forget the emotional impact of Giulio’s death on Maha Abdelrahman and other academic staff. Yet at the same time, could – and should – the University have done more to put pressure on Egypt?

“It’s difficult because we’re having this interview now, but Amnesty was the group that was supposed to be taking it forward. If I’m going to sit here and be like: ‘the University has not done enough’, that’s also saying that we’ve not done enough, and that’s definitely true. But I do also blame that on the fact that everyone felt so unclear about what they were and weren’t allowed to say.”

Bates also suggests a reluctance on the part of the University to take responsibility for what happened to Giulio, wary of setting a precedent in case anything were to happen to other students.

“I think for them it’s a case of ‘we sympathise with him but we are not responsible for him’.”

There is also a suggestion that Cambridge as a wider community should be more active in remembering Giulio’s case and pressing for justice. Banners demanding ‘Verità per Giulio Regeni’ were displayed in dozens of university towns across Italy. By way of contrast, Cambridge City Council refused the local Amnesty group’s request for a similar banner to be hung up from the Council House, saying it would lead to demands for all kinds of political banners to be put up.

“...we’ve all become witnesses to what happened, and we all carry that with us.”

Liesbeth ten Ham, Cambridge City Amnesty

Part of the disconnect may stem from the fact that Giulio is an Italian citizen. Zeichner admits that “people in Britain possibly didn’t fully understand just what a very, very big diplomatic incident it was in Italy. I got the sense because I was trying to follow it when I went to the European Parliament – I got that sense that it was absolutely a major front page news story, in a way that it wasn’t in Britain”.

Both Zeichner and Bates also point to the fundamentally transitory nature of the undergraduate student body. Third years graduating in June will be the last year to have been at Cambridge when the murder took place, and for incoming students to know who Giulio was and what has happened in the two years since his murder.

But the undergraduate body is not all of Cambridge, as Zeichner is at pains to point out: “for the long-term settled University community, Giulio was one of us. And for the many people I know who were very dear friends, two years is not a long time, and people are still very very sad to lose him, and angry about the way in which his life was lost.”

Instead of apathy, Liesbeth ten Ham from the City Amnesty International group thinks that the localised nature of the case, the fact that Giulio walked the same streets as we do now, more people are involved than one might expect. “I have met very few people who are not sympathetic to the case, and who do not know about it,” she says. “Even in Girton [village] my friends also got involved because they heard about the case – they are not the regular human rights defenders that we have met before. It touched a lot of people.”

“Those of us who have campaigned on the case, residents of Cambridge, his friends, colleagues, we’ve all become witnesses to what happened, and we all carry that with us.”

Will there ever be truth for Giulio?

As Cambridge collected outside Great St. Mary’s to remember Giulio, two years to the day since his disappearance, there was solemnity and there was determination, but there was also a question no one wanted to answer: would we be doing exactly the same one year from now?

There are some indications that the truth is getting nearer. In late January chief prosecutor Giuseppe Pignatone confirmed that Giulio had been killed because of his research into independent trade unions. Amnesty International Italy say that a large batch of documents – still in the process of being translated from Arabic – have finally been released to Italian investigators, while Maha Abdelrahman has had her mobile phone and computer seized, though that is likely to be cheered more in the offices of La Repubblica than in the UK.

Those familiar with the case are at varying degrees of hope for the future. Ten Ham of Cambridge Amnesty is at the more optimistic end of the spectrum: “History is never kind to people who commit human rights abuse. Justice is always better if it’s achieved sooner rather than later, but in this case we may just have to be patient, be patient and persistent and continue to campaign. But it will happen, I have honestly no doubt about that.”

Giulio’s friend Laurence Blair is a little cautious, reminding activists that they have to be realistic in their dealings with the Egyptian regime. “Will we see Sisi himself or his top lieutenants going to jail in the next decade or two? Probably, most likely, not. In a couple of decades could we see an admission of wrongdoing from the Egyptian state itself? I think that’s definitely a possibility.”

While Giulio isn’t coming back, people are determined to use his case for some good. Every single party interviewed for this piece emphasised the same thing – that Giulio was not a one-off case, but rather symptomatic of a much wider problem in Egypt of (state sanctioned) disappearances.

“What happened to our friend has got more visibility, because he’s a white westerner, and that’s an unfortunate fact of how the media works. What we want to see as well, and what we believe, is that if there’s more pressure put on the Egyptian government in the Regeni case, that will hopefully lead to broader improvements,” says Blair.

Or, in the words of Liesbeth ten Ham, “he was treated like an Egyptian”.

It is almost impossible to say exactly when the truth will come out. The nature of the Egyptian regime, especially while Sisi remains in charge, may mean that it is years before anyone senior is brought to justice. But one cannot help but feel that the sheer number of involved parties has played some role in this apparent stasis. With three different countries, a university, friends and family not always asking the same questions, it has sometimes been easiest to pass the buck, and to level accusations at others. Yet in the face of the criticism of Cambridge, a resolve to put the attention back on Egypt seems to be growing. Now it is simply a question of whether that will have any effect.