Content Note: This interview contains mentions of death, rape, and communal violence

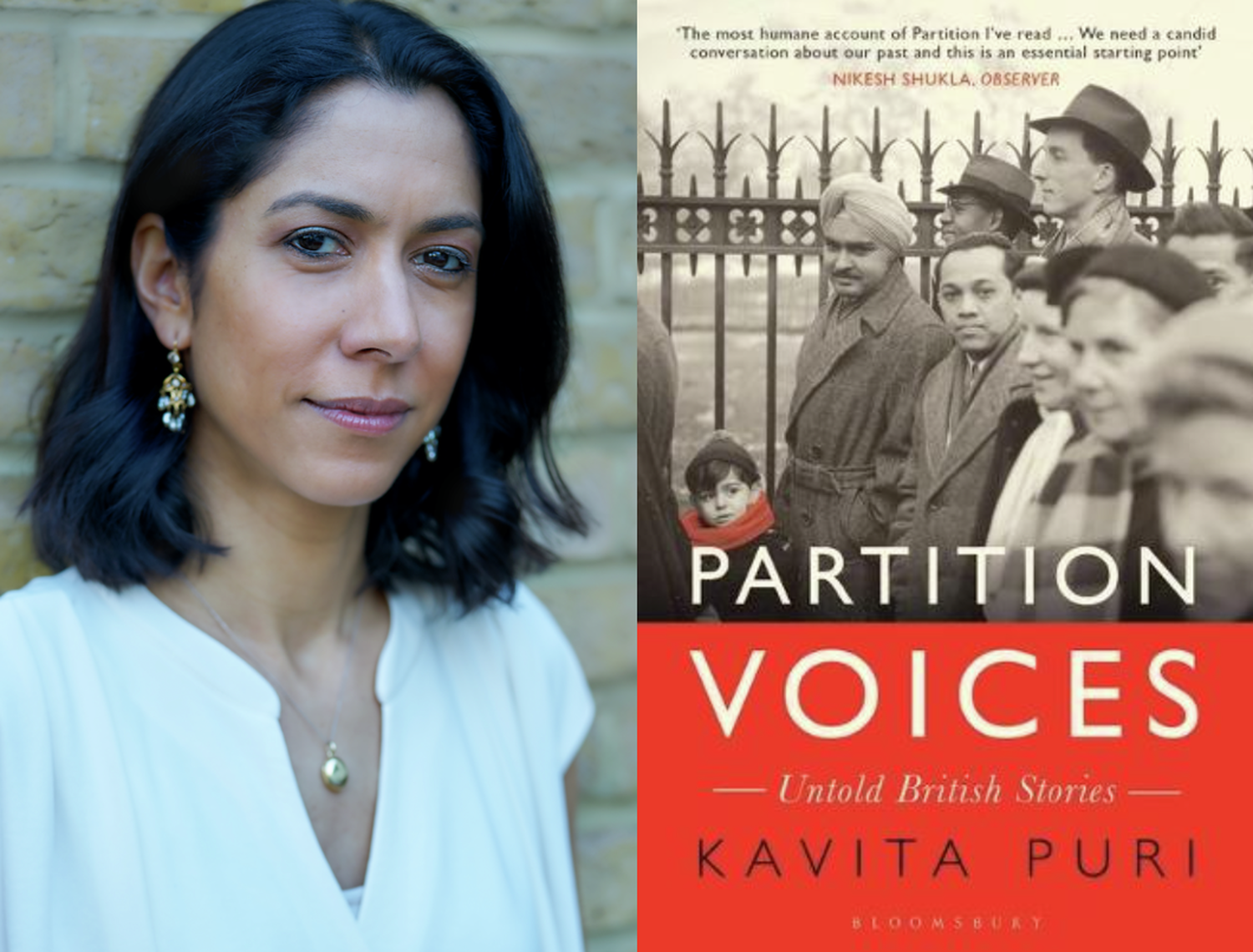

From being ruled by the British Raj to becoming British citizens, the journey of many South Asians from the Indian subcontinent to the UK in the 1950s was a tumultuous one, shaded by a history of loss and separation. They were the years after India’s independence from the British Empire in 1947, and the brutal partition resulting in the two separate states of India and Pakistan. At least a million died, and over 10 million were displaced. Kavita Puri, award-winning journalist, executive producer and broadcaster for the BBC, has recorded a staggering number of stories, experiences, and memories of the partition and its aftermath in her Radio 4 series Partition Voices and book Partition Voices: Untold British Stories.

Many from the partition generation kept their silence about the events of the partition. Their children and grandchildren knew little about what their family members experienced when they were forced to flee their homes. I asked Kavita what motivated her to find and record these stories that many relegate to pained silence. “I suppose it was before the 70th anniversary of the partition [in 2017] and I was very aware that the anniversary was approaching. I’d always known about partition – it was always in the background of my family history, but nobody ever spoke about it. I had really tried to but nobody wanted to talk about it.”

A large number of South Asians who came to the UK in the 50s and early 60s had been directly affected by the partition. Realising that neither she, nor many of her South Asian friends, knew what their parents had gone through, Puri thought: “What if there are other families like mine? I was very aware with the 70th anniversary that if we didn’t try and record these stories, they’d be gone forever.”

“I want to forget it. It was such a bad dream that I want to forget it. I don’t talk to anyone about it”

Determined to record what happened to so many living in Britain today, Puri “embarked upon a project with the BBC”. “At first, we didn’t know what we would find, I didn’t know if people would want to talk ... Eventually, however, we had so many stories that it was impossible to choose from. That’s when I realised all these stories were everywhere in Britain – they were all around us. They always have been we just didn’t know because we hadn’t been told by our families. We hadn’t been taught these stories at school, and so some people didn’t even know to ask their family members.” Through her interviews, Puri realised those affected by the partition came to Britain “with all their stories, their memories, but they just didn’t talk about it”.

“When they came in 50s and 60s, they had different fights on their hands – they had to fight for equal pay, they had to fight against racism. They couldn’t look to the past: they had to look ahead.” And even if they had the energy and capacity to speak about their experiences, it was difficult: “In Britain, nobody was talking about empire. Nobody was definitely talking about end of empire and what happened. And if no one is talking about it, how does anybody know?”

I ask what changed in the last decade or so: “I suppose what happened at the 70th anniversary was that people like me were thinking about that time. It’s also not a coincidence that people who are now in positions of power in the media – they knew what this was and they were willing to commission these kinds of programmes.” More of those who had experienced the partition were willing to speak as well: “When people come to the end of their lives they start thinking about the past. And I think the second and third generations were asking and listening. You have to have a safe public space for people to speak, and that just started to emerge around the 70th anniversary. There is a bigger awareness now – people are starting to find out about their family histories. I have lots of young people contacting me, asking how do I start that conversation, and sometimes, and this is very sad, they say it’s too late for me to ask, and I wish I had asked.”

“This is the brick from the house from which we were forced to leave Pakistan and come to India. There is a personal attachment to the place where I was just six years old … this will keep me reminding of the good old days”

Interviewees often talk about what they lost. Not only their homeland and community and childhood, but smaller memories: a favourite tree they would climb, a lost cricket bat, the smells and comforts of their birthplace. I ask Puri how these specific memories help paint a larger picture of the partition: “I think that when you are dealing with something like the partition, it’s very easy to become overwhelmed by statistics, and the statistics are staggering. It’s the largest migration outside war and famine – approximately 1 million people died, and tens of thousands of women on both sides were raped and mutilated. But, when you look into the individual story, you realise that these are people just like you, they had the same lives like you, they have the same aspirations as you, they had friendships like you. When you draw into the detail of the sadness of not saying your goodbyes to your friends or the sadness of not seeing your family home or the need to see the place that you grew up in one last time before you die – it makes it very real.”

“I think that what it does is it connects people and it shows that the Indian and Pakistani experience was very similar; it connects generations because you can empathise; it connects people who have no relationship to the Indian subcontinent because they can see themselves in these emotions and imagine what if I just had to leave my home? It also connects you in time, because you realise you can go through terrible trauma, and you could live an OK life. You can establish yourself in a new country, you can buy a nice house, you can raise kids and they can have good jobs. But nothing is forgotten. It’s all there. It never went away and that kind of wistfulness for your land or that desire to know what happened to your best friend or that want to see your mother’s grave that is in a land long fled – that never goes away. It’s only when you understand the detail of what individuals went through then you realise how completely overwhelming and traumatic partition was. It didn’t end in 1947 because it still persists today in the people that lived it and in the subsequent generations.”

“The smell of Gangor, I have never forgotten … The memory of those alleyways where I used to run around, used to play … ”

The Hindu–Muslim unity that was lost in the partition was, as Puri says, slowly overcome by those who came to Britain from India and Pakistan and reconnected over their common histories. In light of rising religious tensions in present-day India, I ask Puri what she would want listeners to take away from her show: “We have to listen to that generation. It’s very important to remember, when people give their testimonies, what they tell you and what they don’t tell you. What they wanted us to know, was of course there was terrible violence. But with every story of hate that was told, there was a story of hope. There was a story from one of my interviewees whose father was killed: he was a Sikh man killed by a Muslim mob. It was the same day that his Sikh sister was saved by their Muslim neighbour. There were so many stories like these and what they all wanted to tell us was a much more complex picture than what you’re led to believe exists now from the narratives on the Indian subcontinent. This rupturing was the rupturing of their selves and it was something that people still haven’t come to terms with today.”

The testimonies in the Partition Voices series are now part of the British Library Sound Archives. Puri talked about the significance of this archiving: “When I had initially done archival research in the India office in the British Library, I hadn’t found any testimonies of lived experiences. So, it was really important to me that these testimonies in the transcripts in full were able to be used as a resource for future historians and scholars, but also people who are interested: for my children and my grandchildren. These testimonies should be read side by side with official high-level documents. It was important to me that these testimonies live beyond that generation, beyond me, that they would be there and kept forever.”

Puri is a strong advocate for teaching and remembering the end of empire, partition, and migration as a part of British history: “I think the kind of history that I write about is absolutely British history – it’s our shared history. My interviewees were born as subjects of the British Raj and they now live in Britain as British citizens. Many moved during partition which marked the end of Britain’s colonial rule and they came to Britain because the 1948 Nationality Act afforded them citizenship. So, it’s all about empire and I don’t see how you can disassociate that from British history – it is British history.”

I end the interview by asking Puri about some of her other work on the influence of British South Asians in Britain. She presents a series on Radio 4 called Three Pounds in My Pocket, and covered the daytime secret club movement run by British South Asians. “That was all about the second generation and how the second generation was trying to define themselves. They still faced hostility and so they were trying to carve out a way to express who they were. In the late 80s it was an underground club scene, called ‘the daytimers’. They couldn’t go out clubbing at night partly because they couldn’t get into clubs because they were South Asians and also because their parents probably wouldn’t have let them. They were incredibly entrepreneurial about it and it was really joyful and euphoric. Later on, in the 90s they had their own nights at leading clubs, and it no longer had to be clandestine. It was very reflective of who they were, a real mish-mash of music, of bhangra and hip hop and reggae. It was like them, a kind of complete mish-mash of loads of different kinds of influences.”

As a Cambridge alumna, Puri concludes with a message to South Asians and British South Asians at Cambridge today: “I think it is a great time to be South Asian in Cambridge now. You can be who you are, you can be proud of who you are. You can celebrate your British side, your South Asian side. I feel knowing your history is a really important part of that, and that is now starting to happen.”

A new edition of Partition Voices: Untold British Stories will be released on 21 July for the 75th anniversary of the partition. Series 5 of Three Pounds in My Pocket starts on 8 April on Radio 4.

Italicised quotes are the words of interviewees from Puri’s Partition Voices series.