The first thing you’re often asked upon entering a Cambridge film society isn’t your college or course, but your Letterboxd. Or, more specifically, your Top Four. It’s an introduction that asks you to compress your taste, seriousness, and cultural literacy into four small squares. In a university where intellectual identity is constantly being performed and assessed, even leisure can begin to feel like a representation. This year’s ‘Letterboxd Wrapped’ amplified the prevalence of performative film consumption, filling my feed with screenshots of yearly stats and lists of most-watched actors. I checked mine: 90 films, 136 hours. Had I watched enough? Enough compared to who? This feeling of intrinsic comparison is close to any Cambridge student’s heart.

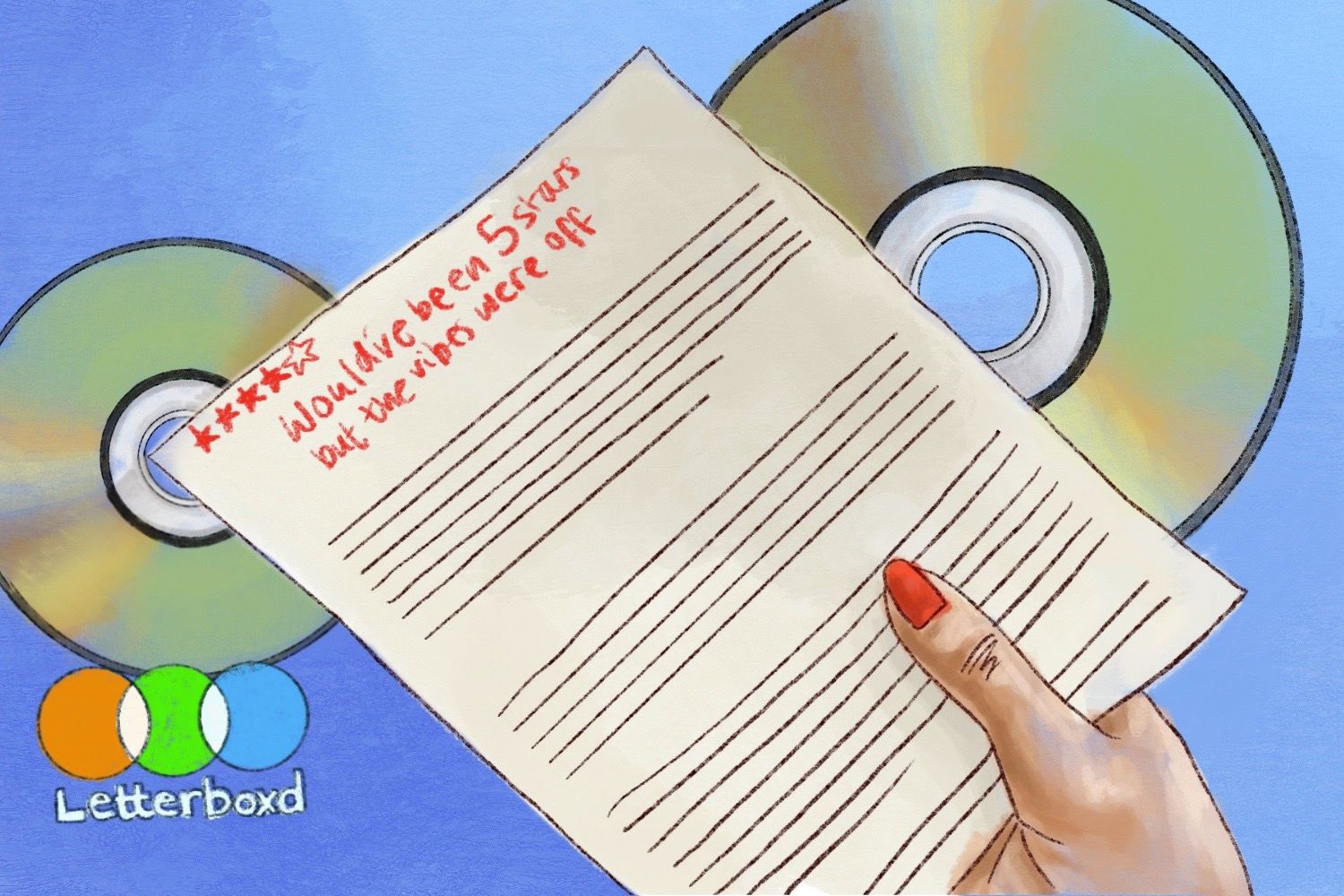

There’s a lot to be said for watching art seriously and deepening our understanding of media. Letterboxd, at its best, facilitates that. Before the app, I kept a physical film diary to log what I’d watched, jot down a few thoughts, maybe rate something so I’d remember how it made me feel. Many users still use Letterboxd in exactly this way. One Engling told me they like it simply because it’s “a fun way to keep track of films, write down thoughts, and see what friends, and the wider public, thought about each film”. Somewhere along the way, though, Letterboxd became a semi-public performance of taste, productivity, and cultural knowledge. In a cultural landscape that celebrates media consumption as achievement, and in a university where cultural capital is already carefully cultivated, I wonder if we are still watching films for ourselves or for the feed.

“Whether it truly reflects your favourites feels almost beside the point”

On the surface, Letterboxd is deceptively simple. An app where you log films, rate them and write reviews if you want to. But there is something to be said about how its design publicises what was once a private record and nudges it firmly into social media territory through public profiles, followers and likes, turning film consumption into something increasingly trackable, quantifiable and shareable.

Of course, none of this is inherently sinister. For many people, myself included, it’s just fun. It helps you remember what you’ve seen, and reinforces a film community, something particularly visible in Cambridge through societies like CUFA or WorldCinemaSoc. However, Letterboxd’s ‘soft gamification’ also introduces a quiet pressure to keep pace with an imagined standard of what a ‘proper’ film fan looks like. Taste is public. Your ratings, lists, and Top Four act as a compressed version of who you are. That makes them feel oddly high-stakes. Stats pages break your viewing into hours, decades, and countries. Lists invite curation. Watching films begins to feel less like drifting into a story and more like keeping up with my ever-growing supo reading list.

There are films that are ‘good’ because everyone agrees they are good. I’m fully guilty of rating a three-star experience four stars because I’d been told it was Important (sorry, Conclave). When taste becomes visible, it becomes adjustable. You start to sense where your opinion sits in relation to the consensus, and sometimes, consciously or not, you begin to shift it.

Several students admitted to feeling a similar pressure. One told me they’ve watched films “partly so I could log them,” especially classics like Fight Club (1999) or The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), but also the A24 canon that dominates Letterboxd culture, from Midsommar (2019) to Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). Watching becomes a way of filling gaps, completing an implied syllabus. This leads into the issue of performance; obscure films signal seriousness and taste, with certain directors or movements carrying cultural weight, while others feel faintly embarrassing to admit enjoying too much. Over time, your profile starts to look like a carefully arranged exhibition of taste. It’s meant to represent your favourite films, but often it becomes a carefully balanced signal: one classic, one international, one contemporary, one wildcard. It signals range. Whether it truly reflects your favourites feels almost beside the point.

“The dominance of irony also reflects something broader about Gen Z online culture”

Another interesting aspect of Letterboxd I noticed while scrolling through the most-liked reviews is the prevalence of witty one-liners. Being the hypocrite that I am, I can acknowledge that I’ve enjoyed both writing and reading them. It’s far easier, and often more rewarding, to dash off a quippy response than to sit with a film’s themes or contradictions. This has led many traditional film critics to lament the ‘death of criticism’. To me, these takes feel dramatic and rooted in elitism. Humour has always been part of cultural commentary, and a sharp joke can reveal something true in a way that a long analysis can’t. Several users I spoke to admitted they skip longer reviews entirely.

One student described these longer pieces as “basically promotions for longer-form articles or film critics linking their websites,” adding that it can feel alienating for more casual viewers “looking for a laid-back way to engage with film”. Quippy reviews, by contrast, are more readable, more shareable, and more likely to be rewarded by the app’s design. However, the dominance of irony also reflects something broader about Gen Z online culture. Sincerity is risky. To care openly, emotionally, or earnestly is to risk sounding pretentious or overly invested in the fear that feels particularly acute in an intellectual environment like Cambridge. Irony offers protection. One student told me they always think about how a review will be received before posting, wanting to seem “witty and funny but still light-hearted” rather than overly serious. Others echoed this hesitation. “You don’t want to be that person,” one said, referring to users who write paragraphs of earnest analysis under a film everyone else is joking about.

So, is Letterboxd ruining film? Probably not. But it is changing the conditions under which we watch and talk about films. Letterboxd democratises film culture in ways traditional criticism never did: anyone can write, anyone can be funny, anyone can respond. It can make film social again, something especially valuable in a university environment built around intense workloads. At the same time, it reproduces the familiar pressures of Cambridge life. In a university where even hobbies can feel evaluative, the most radical act might be watching something without logging it at all, letting a film exist, briefly and sincerely, just for you.