I stand up from a crisp, leather-padded chair, in the assembly hall of a prominent London boarding school. The bevelled edges of the ceiling are covered in elegant, gilded Edwardian carvings, the type of carvings I had seen at every school I'd competed at that month – except, of course, at mine.

I'd just finished my second debate that morning, on a motion relating to austerity and public services. Stepping out of the room, I notice I'm being stared at by a swishy-haired boy in a navy-blue suit. He was on the opposition during that debate, and from a top private school in North London. As I walk past him, he makes direct eye contact with me and shouts: no one actually cares about the working class!

His peers burst into wheezing laughter. I look away and keep walking.

My journey into competitive debating was an unorthodox one. I was a soft-spoken 14-year-old, who had offered to fill in for a few absent students at my school’s debate club. That lunchtime session just happened to be an introduction to British Parliamentary debate – I won on my first try. The teacher running the club had an excited look on his face, and insisted I come back next week. To my surprise, I did. To my greater surprise, I kept winning.

"By 16 years old, I was among the most prominent competitive debaters in London ... By 18, I had quit"

From then onwards, my life was brimming with debate. I took part in competitions with the Oxford and Cambridge Union, beating students two, three, four years older than me. I led my school’s debating society during sixth form and spoke in the House of Commons at 16 years old. The weekends I spent at competitions have now nestled their way into my fondest memories of adolescence: hours spent huddled in hallways with my partner, discussing climate change or animal rights in hushed tones, furiously scribbling ideas on a piece of paper balanced between our knees and giggling with glee when one of us mentioned just the right point.

To this day, I believe debating can be an incredible force for social mobility and personal development. Organisations like DebateMate do fantastic work to build public speaking skills in students from underprivileged backgrounds. Taking part in tournaments was how I got to know people from other schools and countries, how I learned about applying to Oxbridge, how I prepared for the linguistic manoeuvres and analytical rigour that are now central to my English degree. In many ways, I doubt I’d be at Cambridge if it weren’t for competitive debate.

By 16 years old, I was among the most prominent competitive debaters in London, winning rounds against teams from top private schools and coaching students from comprehensives. By 18, I had quit.

The more success I gained as a debater, the more disillusioned and disheartened I became with debating. Gone were the days of good sportsmanship and nuanced arguments from a diverse range of students. By the time I was sitting in that ornate assembly hall, I realised I had now entered a private school boy’s world: a world that seemed overtly hostile to people who looked and thought and spoke like me.

No one likes to talk about the privileges enjoyed by many students that routinely win debating competitions. Tournaments have rules, structures, and covert quotas by which debaters are closely judged. Most private schools hire debating coaches that perfect a student’s ability to deliver a winning speech: they are prepped to know every buzzword, every rhetorical trick, every strategy that puts them at an advantage. If you sat in on a debate round, you’d quickly identify which competitors are from a privileged background, because you’d notice that they all debate the exact same way.

Over the years, I felt increasingly demoralised by the culture of formal debating. There was a feigned carelessness, particularly when discussing some of the most pressing and harrowing topics of our time, that was both expected and praised. The problem was that the issues being discussed – sexual violence, misogyny, wealth inequality – weren’t so distant for some of us in the room. Students barely acknowledged the tragic depth of news reports about famine or conflict; they were just another example to put in the speech repertoire.

In British Parliamentary debate, you are assigned your position. Even if you personally disagree with your side, you must argue for it. It got quite tedious to repeatedly deliver speeches about how public service cuts are good for reducing welfare dependency – a stomach-turning ordeal for someone with loved ones living below the poverty line.

I quickly learned to strike a fine, fragile balance between concern and coldness. My male peers received praise for being aloof and blunt when discussing sensitive issues; female competitors were considered remote and cruel if we did the same. After all, for men, people will focus on what you say. For women, what always matters more is how we say things.

An example that springs to mind is when an opponent referred to me as ‘hysterical’. It wasn’t a coincidence that I was the only girl competing in that round. ‘Hysterical’ has a long, damaging history of being used to dismiss women who speak their minds: the word itself comes from the Latin ‘hystericus’, meaning ‘the womb’. During my speech, the opposing teams would interrupt me or mutter their disagreements, with the intent to knock my confidence. The judge did nothing to intervene; I knew I just had to brush it off.

To become a successful debater, I developed a keen consciousness for how others perceived me. I began to associate my mannerisms and voice with the comments of blunt judges: controlled and robotic, lacking control, monotonous, high-pitched, too cold, too fiery, too bleeding-heart-sincere, not sincere enough.

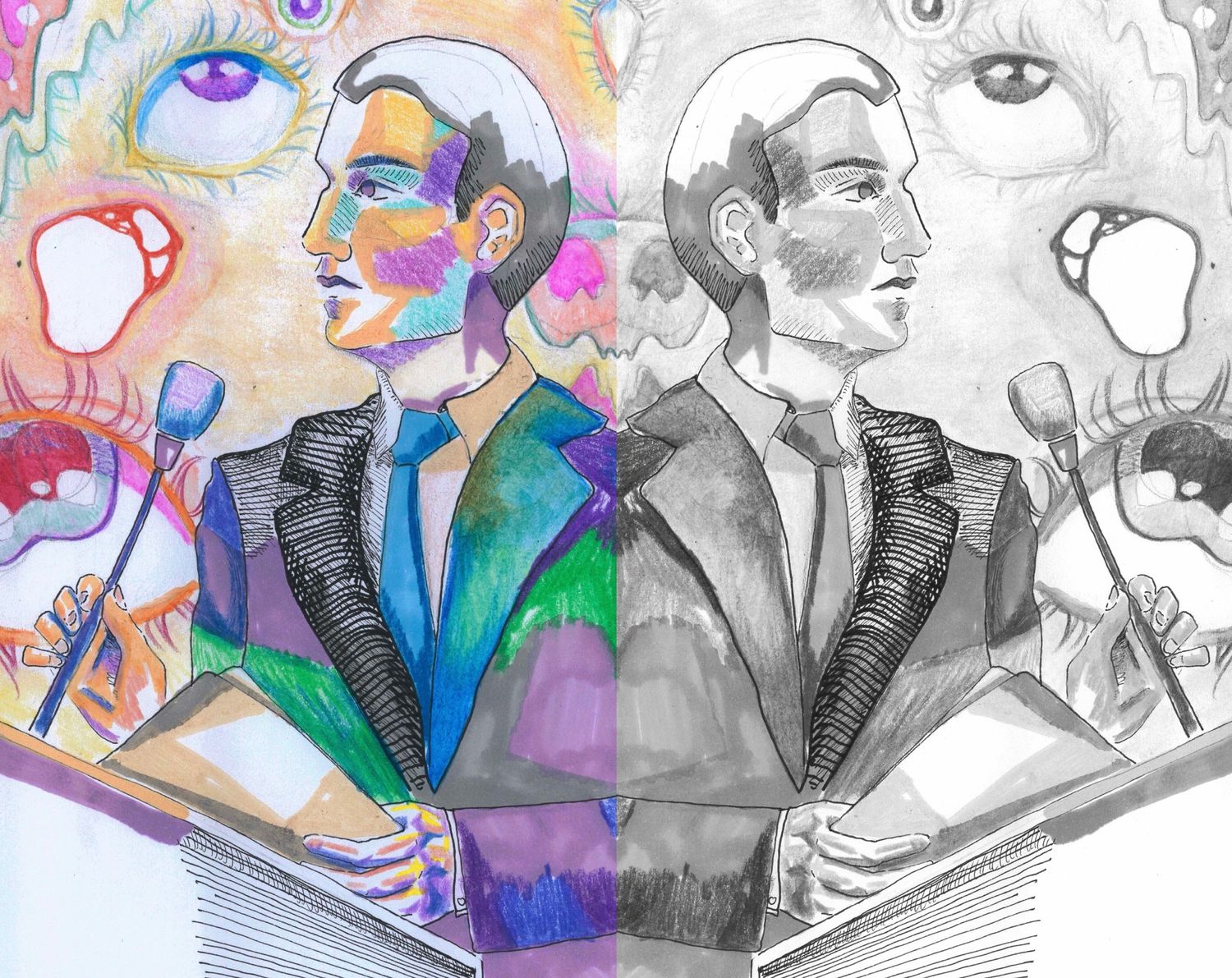

When I first started debating, delivering a good speech felt like watching a bird fly. There was a glamour and ingenuity to the spontaneous passion of it all. But rigorously unpicking and manipulating the mechanics of speech felt like tearing apart the bird's wings and leaving them on a dissecting table. I finally understood the beauty of oration: yet in doing so, I'd lost it.

"a lack of accountability in debating chambers will impact how much these debaters value integrity once they graduate"

But why is this even important? Who cares if some rich kids are dominating an insignificant extracurricular, a pastime that is practically obsolete past university? The answer lies in the real-life, political implications of the structural problems in formal debate: the infamous pipeline of the privately educated debater, to Cambridge or Oxford Union member, to Westminster politician.

Public speaking societies like the Union foster the next generation of leaders. It’s no surprise, therefore, that a lack of accountability in debating chambers will impact how much these debaters value integrity once they graduate. These days, I seem to notice the effects of poor debating practice everywhere: the Prime Minister’s blustering remarks aren’t far removed from the jabs and deflections of the schoolboy debaters I faced.

So, when I passed by the Cambridge Union table at the Freshers’ Fair, I didn’t even look twice. I’ve come to accept that debating – in its current state, and perhaps in its very nature – is deeply ineffective and flawed.

Finally, I feel I can move on from debating: it's served its purpose in my life. Solving our most urgent problems today desperately requires greater empathy and understanding. Most importantly, we need far less of the kind of insidious political posturing seen and encouraged in formal debates.