Content Note: This article contains detailed discussion of anxiety and depression and brief mentions of disordered eating

One week in Michaelmas, during my second year, I didn’t utter a word for three days. I remember it so clearly; waking up after a night of sobs, dragging myself out of bed without showering to make my 10 AM supervision in that building opposite John’s, down the little alley and through the wrought iron gates, where you have to sneak in behind someone to get into the court. Waking up that morning and looking in the mirror above my dimly-lit bedroom sink, in the basement of a Huntingdon Road townhouse, I didn’t recognise myself. Who had I become? From a confident sixth form student who had no problems making friends, who many people once referred to as ‘charming’ and ‘put together,’ I was a ball of nerves, who couldn’t sleep but also couldn’t get out of bed, with a face covered with bloody craters she had neurotically picked from tiny blemishes, and bags that no amount of make-up could conceal.

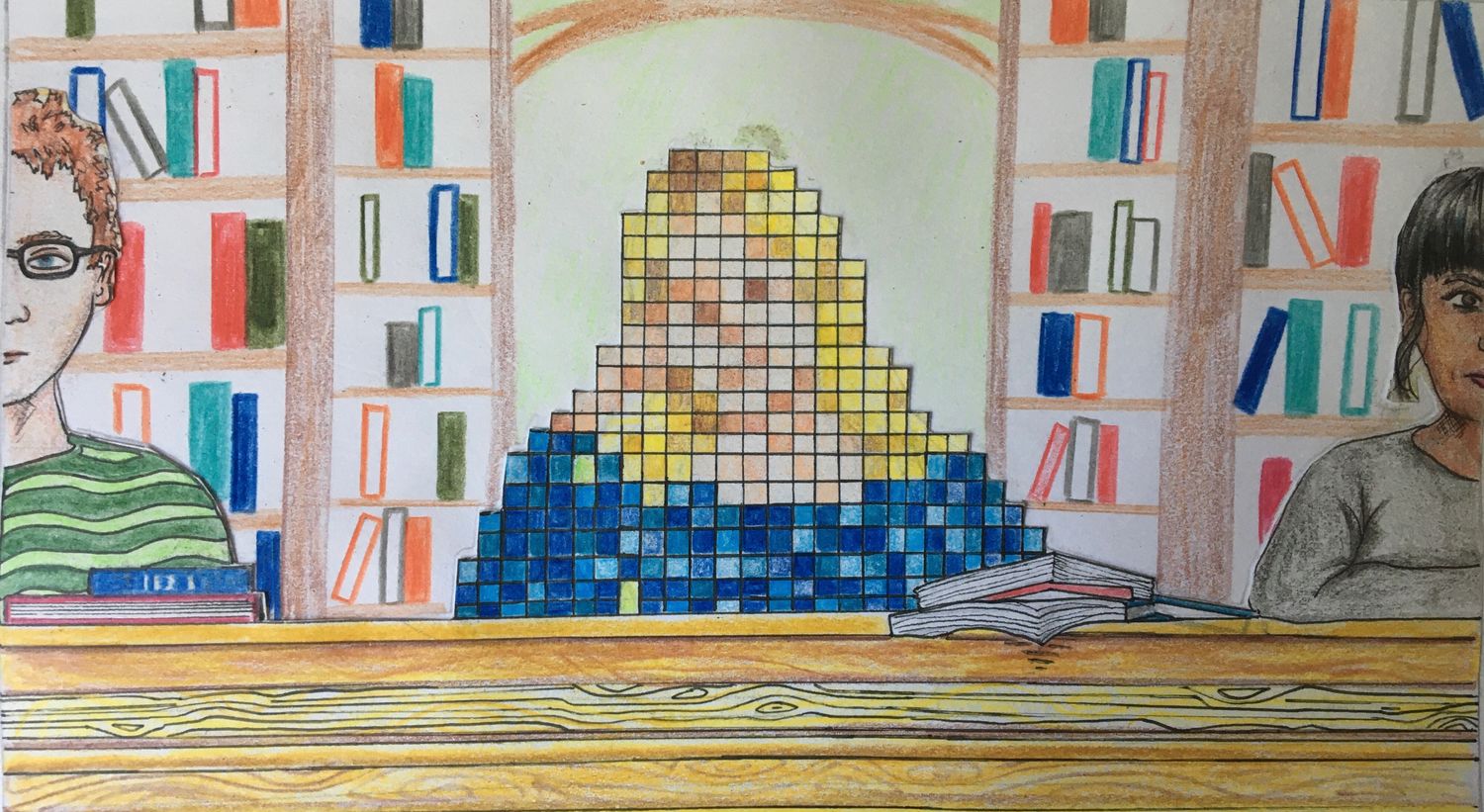

“I buried myself in a nook in the library, ignoring group chats to meet at the cafe for work breaks, and returning to my room for a daily cry”

After scraping my unwashed hair into a slick bun, pulling on some sports leggings and doing the usual concealer dab over tired eyes while brushing my teeth, I left the house without eating breakfast ― another vice I had taken to, where I would go the whole day without consuming a single calorie before eating a bag of five gooey Sainsbury’s bakery cookies in one sitting. I’d usually wolf down this ‘lunch’ on the way home from a lecture, as I’d make the journey to the dreaded chamber. A room which would make me feel particularly bad about myself, thanks to a supervision partner who insisted on turning Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones into an allegorical nightmare - as if it wasn’t hard enough to understand already - but whose intellectual abilities I never doubted because he sounded so confident. This is the same boy who would refuse to share an essay with me for fear of my ‘stealing his ideas,’ because he was of course the only person who had ever thought of them, and this is the paper I would go on to score a high first in, despite feeling entirely overwhelmed in every single class. If I didn’t suffer from imposter syndrome already, it would definitely set in that year. Leaving that session, to which I had contributed a total of two grunts, one mumble and head shake, I walked down Trinity Lane and through the backs, headed for Sidgwick Site but opting to detour and miss my lecture that day. When I got back to my room, I turned the heating up high, locking the door and sleeping. I didn’t tell any of my friends where I was that day, and I spent the following one dodging my peers. I buried myself in a nook in the library, ignoring group chats to meet at the cafe for work breaks, and returning to my room for a daily cry.

“In my head, I lived on the fringes of Cambridge society. Yet on the outside, it should’ve been a breeze”

The worst part about it? No one even noticed, because by that point I was regularly leaving Cambridge to go home to London, or visiting school friends at other universities. I had ‘given up’ making meaningful connections, keeping my guard up, and hiding under a veil of standoffishness which definitely came across as cocky, aloof and pretentious. Who was this girl who couldn’t get her words out anymore, who had lost her sense of humour and any semblance of social skills, who didn’t enjoy any part of going out, who felt pressured to binge drink by peers who could handle a night out without the next day’s depressive episode that she couldn’t shake? For someone who had gone through her teen years generally doing well at school, surrounded by the comfort of close friends who understood me, I felt like I was failing from all sides. From a work perspective, I would go to my classes and feel the pang of intimidation, preventing me from participating, and zone out entirely for an hour, paralysed by the fear of being asked to contribute. But then I’d spend two days diving into research, reading book after book, devouring essays, and finally receiving positive feedback on every assignment I would turn in. In terms of my social life, I would still get invited to every event, despite my friends knowing I wouldn’t attend, and they really did try to involve me, regardless of the fact I would sit at the dinner table with them feeling like no part of me belonged or deserved to be there.

It just didn’t make sense. In my head, I lived on the fringes of Cambridge society, with a sheer inability to get excited about university life and a constant feeling of impending doom that plagued my undergraduate degree. Yet on the outside, it should’ve been a breeze ― I was generally accepted by my peers, and I not only enjoyed, but excelled in my course. Whilst I still struggle to remember those three turbulent years at Cambridge, which I have started to exorcise through writing, I can clearly recall the elation I felt simmering inside on my graduation day. To this day, it is one of the happiest days of my life, and for all the wrong reasons. Sure, it felt amazing to be able to graduate with one of the highest honours you can receive at a world-leading research institution, but that’s not what I had in mind. Walking through those doors at the back of the Senate House, degree in hand, on a thirty-eight degree summers’ day, I still can’t quite find the words to describe the sense of relief that came over me. I was ecstatic because three solid years of anguish, with an equally difficult year abroad in between, I had survived Cambridge, despite all the terrifying moments that I thought I wouldn’t. While friends embraced on the college lawn, I handed my keys to the Porters Lodge, donated my gown to cash in £50 and loaded my possessions into the car.

“I was ecstatic because three solid years of anguish, with an equally difficult year abroad in between, I had survived Cambridge, despite all the terrifying moments that I thought I wouldn’t”

Two years on, and a lot of therapy, medication, processing and panic attacks later, I have come to terms with the fact that my Cambridge experience was disappointing. It’s four years of my life that I will never get back, but also that I would never change. I’m grateful to that institution for forcing me to come to terms with mental health issues I ignored for many years prior, and also for showing me friendship that I have never experienced before. While I found it difficult to connect on a personal level, I am still in disbelief that friends would come and sleep on my bedroom floor to make sure I didn’t hurt myself, who would ask me to leave my door unlocked so that they could check on me. Friends who understood my perspective was warped and paranoid, yet hugged me tighter even so, and those who cooked for me every day when I couldn’t stomach food. Perfect strangers then, but people with whom I now share a special bond, simply because we got to know each other in our darkest hours. Now fully employed, living independently and rather removed from that tumultuous period, I can safely say, university was far from the best years of my life, and it didn’t take long to prove it.