Fashion has long functioned as a political device, used both as a means of control and as a powerful form of resistance. Pink – mistakenly coded as feminine, soft and sweet – is anything but neutral. At the 2017 Women’s March, marchers protesting against Donald Trump’s inauguration wore pink “pussyhats” to create a visual, political statement: the accessory spoke volumes without uttering a single word. This is hardly new. Take the purple, green, and white sashes worn by the Suffragettes – purple for dignity, white for purity, green for hope. These colour choices stood for much more than aesthetics alone. Fashion and politics are evidently intertwined then, the former used to broadcast the latter.

“Looking pretty in pink, it seems, is anything but apolitical”

Contemporary fashion has continued this lineage; bold, contemporary slogans are printed on T-shirts to convey direct messages in front of an audience. When Dior sent models down the runway at their Spring 2017 fashion show, they wore T-shirts, emblazoned with slogans such as “We Should All Be Feminists”. Though the brand was later criticised for commodifying feminism without materially supporting the cause, the controversy this caused is precisely the point. It is clear to see that the runaway has power: it can be a site of visual, political expression that challenges movements, conveys support for others, and forces confrontation and reflection. Looking pretty in pink, it seems, is anything but apolitical.

Political dress is not always as bold or declarative as this. Sometimes, it is coded. If we start by considering the carefully curated outfits of the royals, we can see these codes in action. Bound by constitutional neutrality, the British royal family cannot endorse any one political party, ideal, or movement. At least, not openly. Their outfits though, tell a different story – they express opinions that must otherwise remain hidden. Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation gown, a full-length, heavily embroidered piece, may not look like much of a political statement, but it was stitched with symbolism. The Queen herself had requested it feature the floral emblems of all nations across the Commonwealth too, as well as those she ruled – a gesture of acknowledgement and respect for every nation she was affiliated with.

“The late Queen again managed to deploy fashion strategically”

During the Trumps’ first state visit to the UK, the late Queen again managed to deploy fashion strategically, and implicitly communicate her political stance. In a subtle act of defiance, she wore a brooch given to her by the Obamas on the first day of the visit. Then, on the last day, she wore the brooch her mother had worn to her father’s funeral (make of that what you will…) Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales, can also be seen wearing blue and yellow outfits on several occasions, widely interpreted as her signalling support for Ukraine.

But, of course, political dressing extends well beyond royalty, and well beyond the colour pink. Female politicians often wear suits in bright, striking colours to command authority within institutions historically dominated by men. Many female celebrities make big statements about current issues and debates on the red carpet, using slogans, pride flags, and cultural dress to resist the shift in favouring Western styles. In each case, clothing is a form of announcement.

Political fashion also exists closer to home, here in Cambridge. At our very own Debating Union’s 210th anniversary debate, Baroness Ann Mallalieu (its first female President) donned a long black suit jacket, paired with a white, ruffled blouse, and black trousers, accessorised with a black bow tie. A strong outfit choice for an equally powerful figure, whose career has been trailblazing for women entering male-dominated spaces. The ensemble felt deliberate: a negotiation between traditionally masculine and conventionally feminine elements. This achieved a delicate balance between self-expression and conformity – the same balance which women who attempt to challenge social norms are always confronted with.

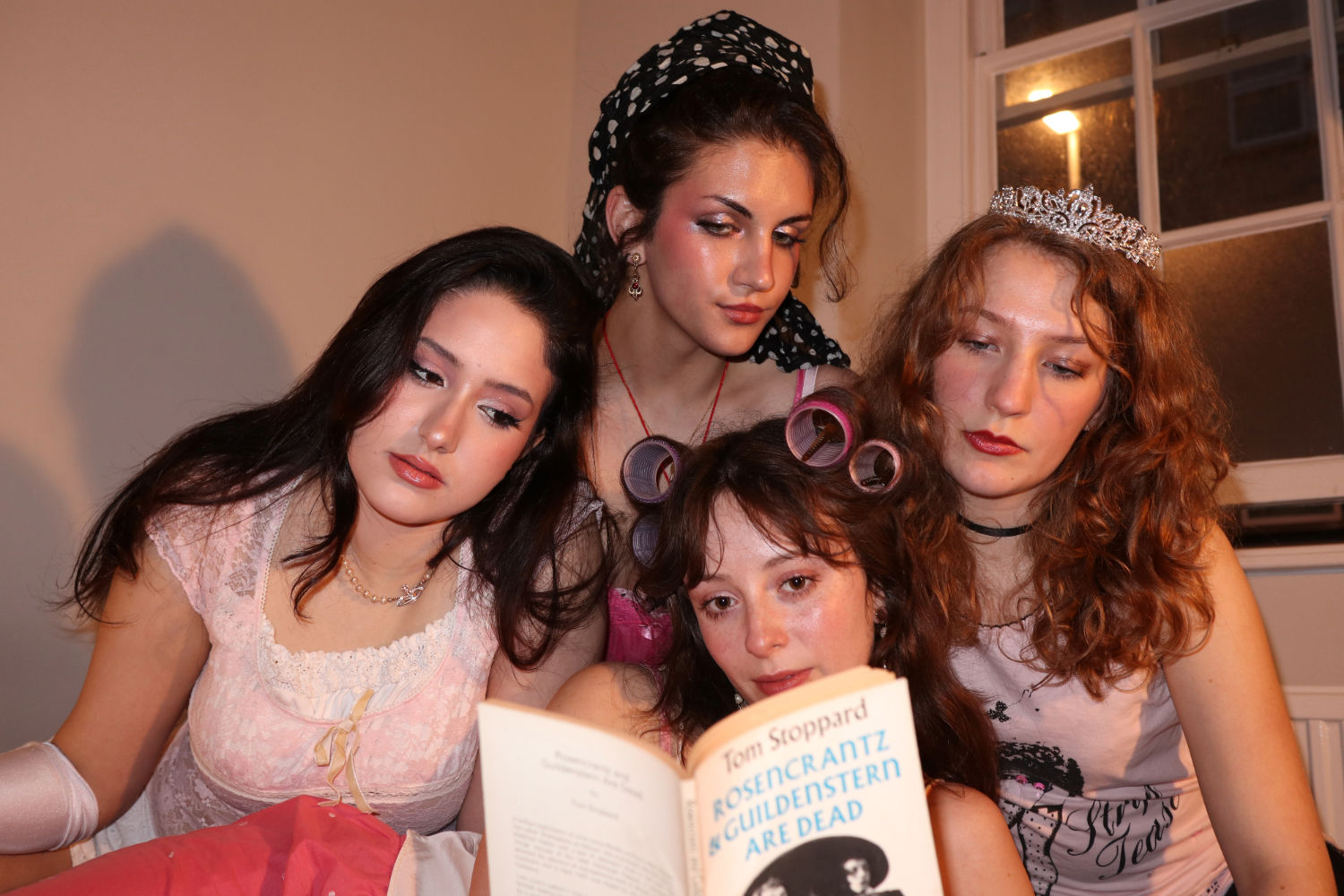

The balance is difficult to strike for younger women too. At a university that demands intellectual rigour and encourages the development of political passion, those who read academic journals, devour political journalism and annotate literary criticism are often those very same students who like to get glam, sleep in pink pyjamas and set their hair in rollers before a supervision. The time and discipline devoted to perfecting an eyeliner flick might mirror the time spent refining the argument of a weekly essay. What has long been trivialised as ‘feminine’, frivolous and vain – the rollers, the blush and the lipstick – might instead signal effort, intention and commitment: glamour is our weapon, and those who wish to wield it, should. Presenting yourself as polished in a place that once barred women altogether is not accidental, it is political – we are now free to demonstrate unapologetic femininity while excelling academically, and this is less about decoration than declaration. So before you dismiss the glamorous woman on Sidgwick (who may well have woken up hours earlier to perfect her flawless makeup) stop to consider what her efforts might truly represent.

As society continues to restrict women’s fashion to the feminine, the ornamental and the indulgent, and the world around us becomes increasingly politically charged, it becomes all the more important to consider the political potential of outfits. They respond to the world around us. Whether you articulate yourself through a sharp suit, a slogan T-shirt, or symbolic colours, the clothes we wear can have a huge range of political implications. Fashion is not superficial, nor impartial. It has and will continue to render politics visible. The only question is: are we paying attention?