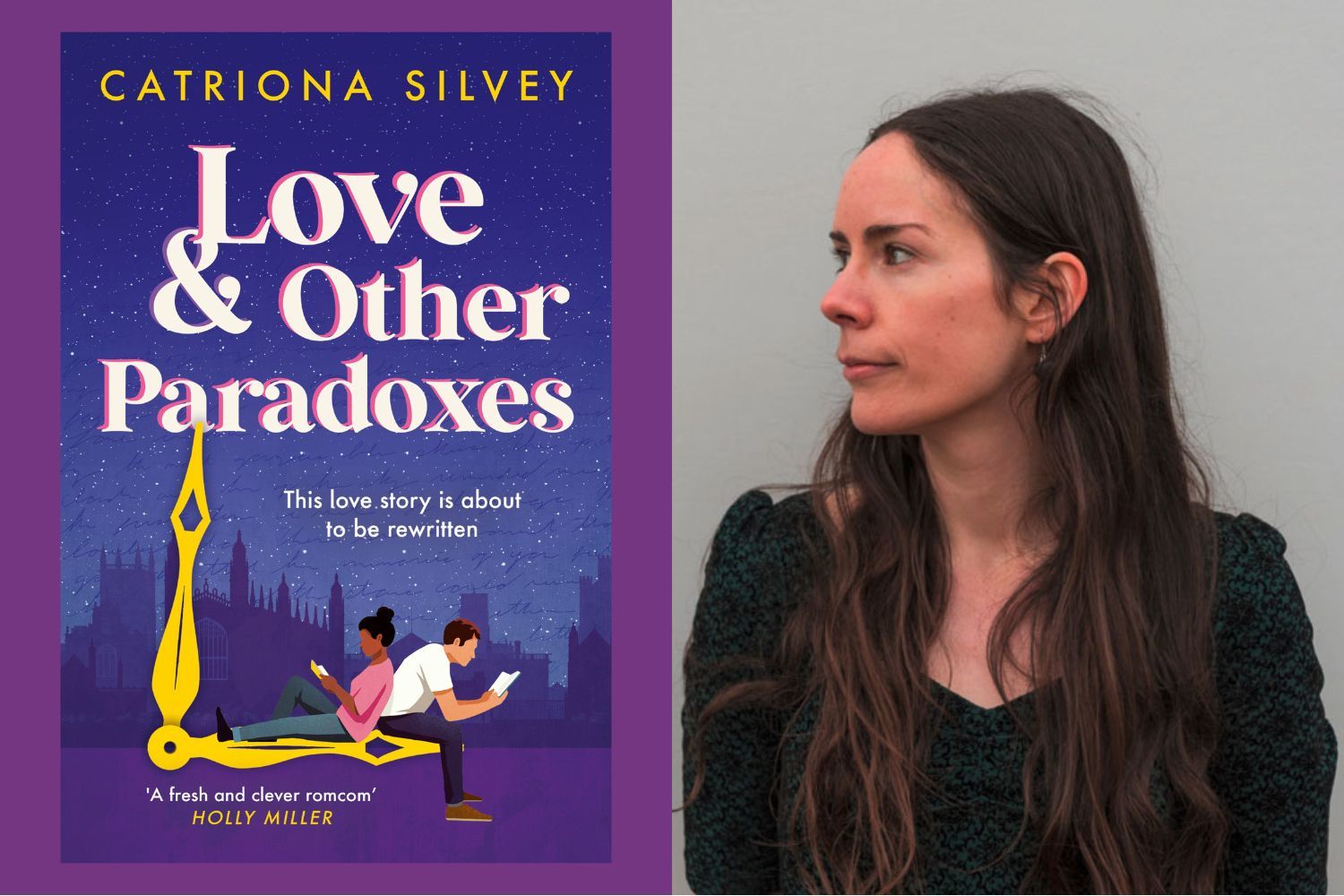

There are two regular complaints Cambridge students make about the city: how differently time moves here, and how it makes getting into a relationship near-impossible. But however much they plague us, these aspects have provided perfect writing material for Catriona Silvey, whose latest romance novel relies on a time-travel wormhole in the centre of Cambridge to bring its protagonists together.

As a Corpus Christi alumna, Silvey immediately acknowledges that the “texture of student life is going to have changed so much” since the early 2000s Cambridge in Love & Other Paradoxes. But Cambridge is also “a place that clings to the past,” and we’ve seen the institution’s traditions clash with residents and students enough to know that it’s constantly colliding with the present, even without the novel’s time-travellers.

Being a student also makes the connection between periods of your life more tangible, Silvey recognises. “You’re very focused on the present, but also the future is coming at you like a truck,” she tells me, appreciating that, as a finalist, I’m quite familiar with this feeling. But her book inverts the common panic-inducing question of “what do I do with my life?” and instead proposes the possibility that future success could simply be a pre-written script. The author does accept that responses to a novel so deeply embedded in Cambridge will “probably be deeply individual” – in fact one of her friends refuses to read it because “she doesn’t want to revisit that time in her life at all”. Personally, I expected picking up the novel after I’d barely scrubbed the celebratory Cava out of my hair would be a somewhat jarring experience. But after discovering the protagonist Joe was also a finalist struggling to meet expectations of academic success, I found it to be a surprisingly reassuring read.

Unpicking the thought process behind him, Silvey says Joe essentially “thinks that he needs external validation in order to be worthy of existence” – probably “the case for a lot of the type of people who end up at Cambridge”. While I felt slight aversion upon opening the novel to find him standing in adoration beneath a Byron statue in the Wren Library, I quickly realised that Joe is only a slight exaggeration of around ten people I’ve met here – and a scarily accurate portrayal of at least one. His all-or-nothing mindset, believing “if I don’t become an incredibly famous poet, my life is over,” is supposed to be “a little bit ridiculous” – but Silvey knows it can also be relatable when you’re surrounded by the legacy of famous alumni, and “the expectations, even if they’re never directly stated to you, can feel really, really high”.

“Listening to her explain how Joe’s rejection from The Mays was based on her own, I realise that Silvey’s career is a surefire sign that early rejection is not a measure of future success”

As inspiration, the author also cites her own experience of being “a complete mess when I was twenty-one”. While she felt “more at home in Cambridge than Joe did,” his background of coming from a rural Scottish school “that hasn’t sent a lot of people to Cambridge in the past” drew upon her awareness of the snobbery against anyone not from the southeast of England still pervading Cambridge today. Yet by deliberately giving him the advantage of being a man to make him a “kind of insider-outsider,” Silvey constructed a protagonist to bring the reader both sides of the Cambridge student experience: the privilege and the insecurity. This balance even feeds into Silvey’s amalgamation of sci-fi and realism, with the time-travel wormhole’s location of Piss Alley perfectly capturing the contrast between touristic facade and grimier reality.

Listening to her explain how Joe’s rejection from The Mays was based on her own, I realise that Silvey’s career is a surefire sign that early rejection is not a measure of future success. After I inquire whether she pulled off producing creative projects while churning out weekly essays, she reveals that, while she knew she wanted to write books “before I remember knowing what wanting to do something with your life was,” she “wasn’t very serious or dedicated about it for a long time”. Yet this self-proclaimed “lazy” approach became crucial to her process. While studying English to improve her writing, it was the memories she made that fuelled her creativity. This informs Silvey’s main advice for anyone struggling to get started: “if you don’t have life to draw on, you’ll write something that seems like it’s based on other books”. She knows this advice can be hard to swallow in an environment oversaturated with overachievers, but states firmly that she’s an advocate of writing “in the corners and in the spaces in-between, and your writing will probably be more interesting for it – unless you happen to be a genius who can just write a publishable novel when you’re eighteen.”

While two years living just off Mill Road clearly fed into Silvey’s intricate representation of the city streets, she’s lived a lot of life outside this bubble. A prolific academic, she almost forgets to mention that she completed a Master’s in Chicago, before her MA and PhD at Edinburgh. “So that’s two real Master’s, one fake Master’s, and a PhD”, she laughs. But while she feels she should cite “all of the canonical novelists that I studied” as influences, her real debts are owed to science fiction and fantasy. Reading Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series “probably before it was age-appropriate” not only influenced the sci-fi slant of her latest novel, but also her writing style. “I loved the way that he writes comically in a way that seems so easy,” yet is actually “really, really, super hard”, she says – but observes that comic ‘TikTok-writing’ is rarely seen to be as serious or artistic.

“It’s this sense of the importance of enjoying the present – in spite of a future that will always stay stubbornly out of our control and beyond our imagination – that stays with you long after you put her book down”

On top of her many degrees, Silvey’s previous novel, Meet Me in Another Life, placed at no.2 on the Waterstones bestseller list – and is also preoccupied with the paradox of whether we can change our fates. When I asked if writing repeatedly about time travel has changed how she sees her own past and future, Silvey says that moving from Scotland to England aged six – “shattering” her “context and reality and identity” – left her wondering “what the version of me that stayed in Scotland […] would have been like”. She’s “kind of terrified by how accidental a lot of really important things seem to be,” with her happy marriage, leading to two children and a life in her favourite city in the world, merely down to her talking to the right person at a wine and cheese night. “That kind of thing cannot depend on how much cheese I wanted to eat that day,” she laughs. Ultimately, she copes with the “opposing terrors” of free will and determinism by creating characters with these opposing views, and plotlines ending up with a “messy compromise,” jokingly admitting that “writing is therapy”. As Meet Me in Another Life has been optioned for a film starring Gal Gadot, this therapy certainly seems to be paying off.

So in a world where even time-travel is possible, can Cambridge finally become a place for finding love? While the novel ends tentatively, assuring only present happiness rather than a ‘happily ever after’, Silvey tells me this was deliberate – partly because very few people stay with the person they met at twenty-one, even without the added complication of being from separate time periods. But she also felt it would be “inconsistent to the themes of the story” if the ending asserted this was “definitely always the way it’s going to be,” instead wanting to leave the pair with the feeling of “possibility as a positive thing,” rather than “a sense of completion” or seeing the future as a paralyzing “source of terror”.

Silvey is a writer constantly questioning the toxic “expectation that your romantic partner is everything to you” usually central to the romance genre; asserting “I don’t think one person is ever enough”, she tells me “we all need a village around us.” The novel is a manifestation of this ethos, made up of several strong relationships which prevent it from feeling like everything hangs upon the success of the central love story; mere minutes of affection shared between a mother and daughter form some of its most powerful moments, simply because they are so fleeting. It’s this sense of the importance of enjoying the present – in spite of a future that will always stay stubbornly out of our control and beyond our imagination – that stays with you long after you put her book down. Whether you’re a fresher wondering how your Cambridge years will pan out, or a finalist facing a gaping wormhole into the rest of your life, that’s not a bad book-shaped reminder to pick up this summer.

Love & Other Paradoxes is out now in all major book retailers.