One night in 1882, something happened to Arthur Benson. Then an undergraduate at King’s, who would go on to be a celebrated poet and master of Magdalene College, he obsessively journalled the anniversary of his “great misfortune” for the next 60 years: “it was in these rooms that I passed my darkest hours – it hardly does to think of now – and yet it was so fantastic and unreal”. Whatever happened to Benson, this experience lives at the heart of King’s College’s queer history – a history which lives at the heart of the college itself.

This was far from the first thing to happen in the rooms of H staircase, and far from the last. Benson’s sexual identity during a time of outlawed homosexuality was centred around his room, H1, as was that of its previous occupant, J.K. Stephens, and of M.R. James, who took the room after Benson. In his book Queer Cambridge, Simon Goldhill, a Classics professor at King’s, sets out to map the extraordinary gay history which unfolded around this room and those surrounding it.

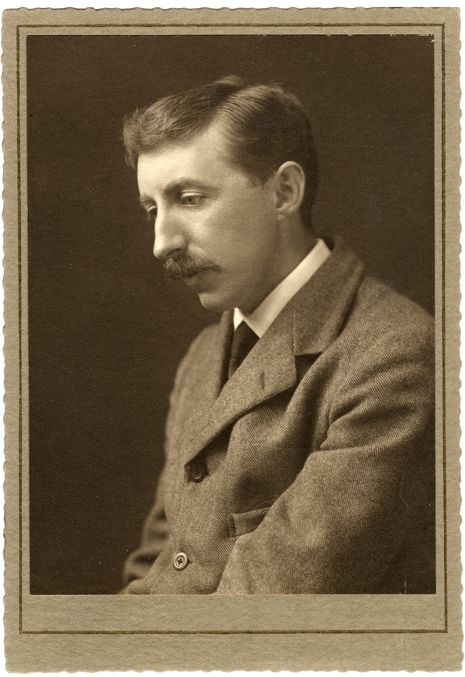

Goldhill’s history of homosexuality at King’s begins before such a category entered use, and includes the lives of novelist E.M. Forster, economist John Maynard Keynes, and mathematician Alan Turing, among many others. Compared to the famous Bloomsbury group, who also have history at King’s, this group of men was “a real community,” Goldhill tells me, “not just a group of friends from different areas, a community that lasted over time,” rooted in the brick and mortar of the Gibbs Building.

As we evade the sun in the generous shade of the college’s Webb’s Court, Goldhill explains that Cambridge’s peculiar architecture was a vital factor behind the emergence of this unique community: “a lot of the college is and was designed for intimacy.” He recalls: “when I was here as a student, the bar was made of little circles where you were expected to sit in a clique.” And on a practical level, while social attitudes to homosexuality changed drastically across the period covered in Goldhill’s study, “the simple fact that you could shut the front door” was vital. The walls and courts of this college retain memory and identity to a vivid extent. Michael Proctor, a former King’s provost whose current office is on H staircase, agrees: “the ghosts of the many fellows who have lived here since the 18th century are definitely present”.

“The walls and courts of this college retain memory and identity to a vivid extent”

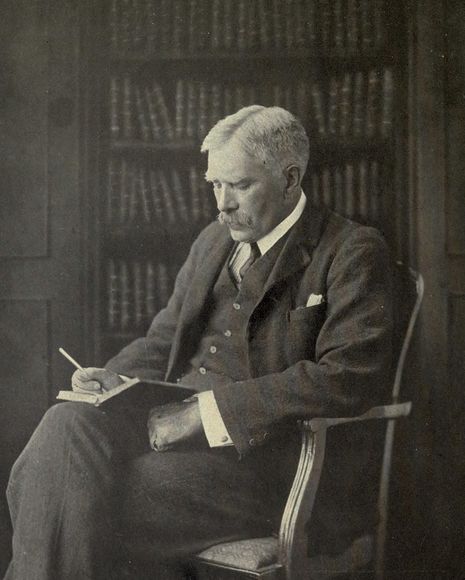

For some of Proctor’s predecessors in H staircase, their academic and sexual lives were blurred together under the pressure of this intimate living environment. For Charles Ashbee, a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement, and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, a pioneer of the League of Nations, “homosexuality was not merely a personal matter, but intimately tied into a political and social vision,” Goldhill writes. This is yet another characteristic of this community that was influenced by their unique environment, Goldhill explains: “They were writing and talking and thinking at the same time about their academic lives and their personal lives, there was no gap between those things.” Dickinson, for example, was a scholar of ancient Greece: he delivered popular radio broadcasts on Plato and accordingly grounded his understanding of sexuality in “a history of Greek culture and values”. Such a blending between academics’ personal and scholarly lives continues in Cambridge today, Goldhill jokes: “It’s like when people say ‘you should go on strike’: what do you mean, I should stop thinking?”

John Maynard Keynes, who moved into the Gibbs Building the year Forster left, was mocked by some, namely writer and critic Lytton Strachey, for letting his academics bleed into his sexuality: “he brings off his copulations and speculations with the same calculating odiousness; he has a boy with the same mean pleasure with which he sells at the top of the market.” The spikiness of this assessment is not rare in Goldhill’s account of these men. Each experienced and reflected upon their sexuality so intensely that these convictions often clashed.

“The ghosts of the many fellows who have lived here are definitely present”

One more problematic aspect of this history, and one which Goldhill is keen not to shy away from, is the student-staff relationships that regularly occurred here. In the book, Goldhill finds that age-imbalanced couplings were “on occasion profoundly unwanted,” while at other times “explicitly sought out by the younger men.” Goldhill explains that he intended to face up to the full spectrum of sexuality in evidence in this history. While student-staff relationships are now the subject of strict regulation, Goldhill points out that, “in those days, people just didn’t think about it in the same way. I thought that would be an interesting moment of historical self-awareness.” The elitism of much of this story is another count on which Goldhill is bracingly realistic. The people discussed in this book are exclusively white, exclusively male, and much of this account is inseparable from the college’s past as an institution reserved exclusively for Old Etonians. While society’s understanding of queerness has widened considerably since this time, Goldhill is committed to uncovering the vital contribution these men made towards modern understandings of sexuality.

The contagious enthusiasm with which Goldhill celebrates the lives and sexualities of these men is an important part of his mission statement. “I think the lonely, miserable, upset bit of gay has been covered,” he says, “so finding a community that was actually comfortable with it is such a revelation that it’s worth telling that story.” Felipe Hernández, an associate professor of architecture who, like Proctor, has his office on H staircase, stresses the importance of this reclamation. The book, Hernández tells me, contributes to “a growing body of scholarly work” on queer histories which, “in other contexts, are often framed by hardship and struggle”.

In describing E.M. Forster’s “repressed but purposive” sexual politics, Goldhill hits upon the remarkable energy of this collection of lives. Seeming contradictions such as these shed light on the unlikeliness of these stories by which pioneering queer dialogues took root at the heart of the British establishment. And though the book takes a broadly chronological approach, acceptance did not arrive in a ordered fashion, Goldhill stresses: “It’s not a linear, teleological story, where we start with the Victorians putting doilies around everything, including sexuality, and we end up with the 60s and everybody’s naked and dancing and fucking each other. It’s not like that.”

Proctor explains that the continuation of this history is not guaranteed even now; he seems to accept that these men are “ghosts inhabiting a space that no longer exists”. He notes that the changing geography of the college is rendering it less hospitable to communities like these, pointing out that neither students nor fellows live permanently in the Gibbs Building today. “At night there is very little activity, illicit or otherwise, save only the choir which meets as it has for generations at the bottom of H before the daily Chapel service,” Proctor says.

As well as the buildings of Cambridge, societal attitudes could begin to close up too. Goldhill worries that, while the language around queerness has expanded vastly since the lives of these men, society’s willingness to hear these stories is not guaranteed. The “liberal tolerance” that allowed these sexual identities to flourish behind closed doors is “greatly under threat,” Goldhill reflects. “Not because a few students are misbehaving. It’s under threat because of Donald Trump and [Victor] Orbán and whoever you want to name, Erdoğan, the Italians, the Greeks, the whole lot,” he says.

Atlanta Tsiaoukkas, a representative of Cambridge’s LGBT+ society, is aware of the threats posed by this intolerance. While Goldhill’s narrative is “a timely contribution to our knowledge of past queer communities, there is much more to be done to recoup queer histories and presents in Cambridge,” she warns, particularly for the university’s transgender residents, for whom the “battle for equality” persists.