I remember you. I know your face. Yeah, yeah, see I’m not good with faces but yours I’ve not forgotten. You remember the old neighbourhood, right? Of course you do, come on. You moved, I think your dad got a pay rise or something, anyway, you moved away and I never saw you again. I think they probably didn’t want you going back, which is fair enough. All things considered, definitely fair enough.

Come on though, we had fun didn’t we? There was a gang of us, we used to play out in the street together. I mean, it was a miracle none of us got hit by a car or anything. Not really a neighbourhood of careful drivers. That didn’t worry us, though. Nothing worried us. Those were properly halcyon days. Summers like you don’t get in scummy old England, summers you only find in American novels. Practically make-believe.

What was it we used to play again? Yeah, that was it, we made up worlds. Whole worlds, and we populated them with knights and monsters, heroes and villains. We were always the monsters. Being the knights just seemed a bit too obvious. Come on, you must remember this. You do, you surely do.

Oh yeah, we used to spy on people too. That I do regret, in retrospect. When we’d tired ourselves out with our own games, we crept up to people’s windows and watched them. We justified it, though. We weren’t breaking into their world, no, we were making them a part of ours. That couple, that young couple that always used to fight: he became a prince and she a princess. He’d rescued her from the goblin king but she wanted to go back. She’d quite liked living in the fens.

Then there were those two old men who lived together. I mean, hindsight is twenty-twenty on that one. In our imagination they were two ancient oaks, their roots all tangled up so they could never leave each other’s side. I think maybe on some level we did get it after all, even though we were just dumb kids. Anyway, we never watched them for that long. They weren’t really that interesting.

The magician though, yeah, he was pretty interesting. The magician, who lived at the end of the road. You remember the magician, right? No come on, seriously, you must remember the magician. You don’t? You don’t at all? Are you… no it’s definitely you. It is, I know your face, I’m sure of it. I’m not getting confused, I swear I’m not. I just can’t believe you don’t remember the magician.

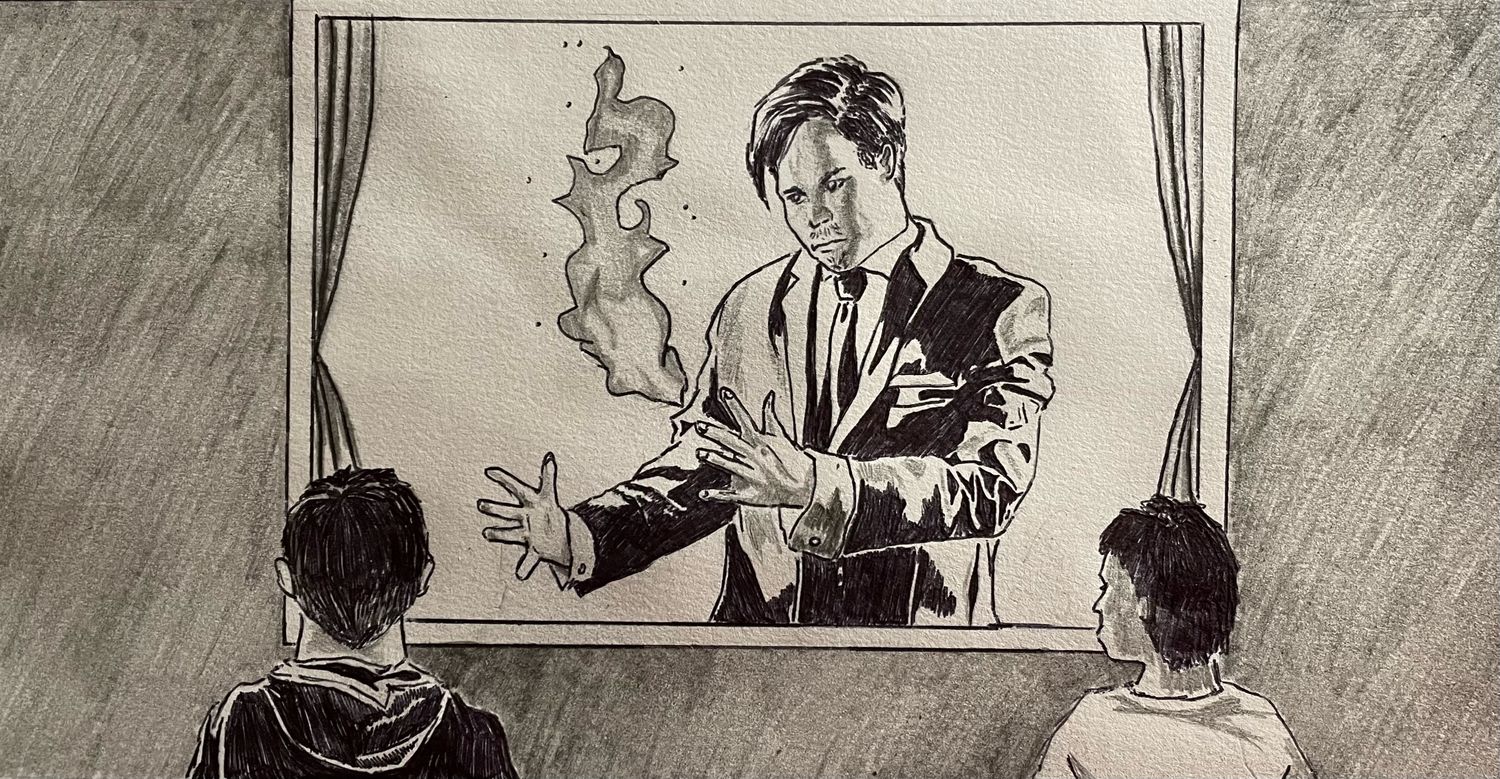

He was the only one that ever noticed us. It was like he had some kind of sense: every time we drew close to the window he’d look up from his desk and see us peering in at him. Most of the time he’d push his chair back, get up and come striding over. We never waited around to see what he was going to do. There were other times, though, when he’d just smirk at us and continue with his work. Then we’d stare in at him with wide eyes. We’d watch, a little awestruck, a little frightened, as he performed his magic.

My memory is pretty blurry, pretty imperfect. Still, when I close my eyes, when I squeeze them tight shut I can still see him very clearly. The magician, hunched over his work, brow furrowed and eyes gleaming. He draws coiling symbols on little squares of paper, arranges them on the desk in front of him. He opens a little black box, takes out these carved pieces of ivory. Carefully, gently, he positions them, he forms a pattern only he can understand.

There’s chanting, muffled by the window pane but just about audible. He moves his hands over the objects on the desk. The light flickers, is sucked from the room. We watch, eyes wide. Then at once he slumps back in his seat, as if exhausted, and the light returns. Looking up at us, he grins. We flee.

I’m sure you do remember. I saw it playing out behind your eyes just then, as I was describing it to you. You don’t want to admit it but you were there, you saw what he did. Come on, say it. My words jogged something, right? You thought you’d forgotten, didn’t you? You thought you got rid of it but it’s still there. Sorry.

I mean, obviously we thought it was amazing. There was a magician living on our street. Whenever there was a light in his window we’d go creeping up to take a look. Nine times out of ten we were chased away but every so often we’d get to watch. We knew without being told that what he was doing was forbidden. This, obviously, only made it more exciting.

We didn’t tell anyone. Not our parents, not anyone. We didn’t tell them what we saw, not even when the bad stuff started happening. To be fair, we didn’t make the connection at first. It took us a little time to figure things out, for everything to line up.

“We knew without being told that what he was doing was forbidden. This, obviously, only made it more exciting”

The first thing we noticed was the absence of the princess. One day she was simply gone, the prince left alone in an empty house. Amelia, who lived next door, said she’d woken in the middle of the night and heard them screaming at each other, louder than ever before. It had really scared her, just how angry the prince had sounded. A door had slammed, a car had started. Silence returned.

From that day the prince was mired in silence. He’d just sit around watching television, bathed in the screen’s sickly light. It would swamp him, get sucked up into his pores, infuse him. He looked bloated, looked at all times like he wanted to vomit. We didn’t feel much pity for him and we quickly grew bored of his lounging.

A few weeks later, one of the ancient oaks disappeared. It took us longer to notice, for it happened quietly. The other oak continued, though he seemed smaller, more withered. Now he drank his morning cup of tea alone from his armchair. Now he moved about an empty, silent house, aimlessly. The roots that had bound him so tightly to the earth had died.

There were other things, worse things still. Mark’s older brother went out one night and never came back. For the next few weeks Mark didn’t come to play with us. When he finally returned, he wouldn’t talk about it. We knew already, of course. The truth was whispered in the pattering of rain on our windows, in the sweltering heat that rose up from the pavement. Mark’s brother had been stabbed.

I don’t recall who it was who first made the connection, who first suggested that the magician might be the cause of all the badness in the neighbourhood. Once it was spoken, once someone had given it voice, it became so self-evidently clear that it seemed like we’d all of us known it all along. It was a little dark, nasty secret flitting amongst us, waiting for its moment, waiting to be spoken, to be given weight. It took hold of us, this heavy certainty. Of course the magician was responsible.

We felt guilty, of course, for we’d been watching him all this time, working his evil, and we’d done nothing to stop him. For a while we just tried to forget it, tried not to talk about it. Maybe it would just go away, maybe the truth would just dissipate and stop bothering us. We knew we couldn’t tell the adults. I got a sick feeling in my stomach whenever I thought about it. Like my heart, my lungs, my ribcage, all were made of glass. One wrong move and I might shatter. The others were the same, I think.

Not you, though. You were braver than the rest of us. Do you remember? Come on, you do, you do. You must. It was you that did something, in the end. Of course you remember. We used to walk home from school together, the two of us, and our path always took us close to the magician’s house. One day we were going by and we saw him coming out of his front door. Do you remember what you did?

“Hey!” You shouted at him. I think it probably startled me more than it did him. He glanced up, adjusted his glasses on his nose.

“We know what you did,” you wouldn’t shut up. I wanted to tell you to stop shouting, to be quiet, but I couldn’t find the words.

“Hmm?” The magician only looked confused.

“We know what you did to the princess, the ancient oak, Mark’s brother.” You counted them off on your fingers. There were other people too: the list was quite long. I think you used their real names but after all this time I can’t remember what they were. Do you remember what they were? No? You knew then.

“I’m sorry,” the magician came down the steps at the front of his house, “I really don’t understand what it is that I’m supposed to have done.”

“You know what you did. Admit it. Admit you did it.”

The magician gave a little exasperated grunt. Then he reformulated his face into an expression of patience, holding up his hands all innocently.

“Look, I don’t really understand what you think I’ve done but I assure you, I didn’t have anything to do with any of these things. I was really sorry to hear what happened to your friend’s brother. Honestly it’s been a tough year for everyone around here, I know. I think maybe you guys need to have a talk about this with your parents. Why don’t you head home? They’ll be wondering where you are.”

You glared at him, lip curled, but he only looked back at you with infuriating calmness. I was tugging on your elbow, eager to get away. For a long time you resisted me, stared him down. Then finally you gave in and we scurried away down the street. Before we could get out of earshot, though, the magician called after us. There was something in his voice that made us stop dead still.

“I understand your mistake. You’ve seen what I do, you’ve seen things you weren’t meant to see, you’ve drawn conclusions. You should know that I don’t influence matters, I only observe them. It’s the most natural instinct in the world to want to know, to want to glimpse the truth. That’s why I let you watch: I know you’re curious too. Well, your curiosity is rewarded. Let me tell you what it is that I’ve seen.”

He pointed at me. I shied away from his finger.

“You will be the first. There will be an accident. It will be quick, so quick there will be no time for you to register what is happening.”

Next he turned his eyes on you.

“You will be the second. You will be caught up in a war in a foreign land, far from here. For you the tongue will be pain and blood. You will hear shouting and screams, but only faintly. Then there will be darkness and silence.”

He shook his head, made a clicking sound with his fingers.

“Sometimes,” he murmured, “to see is just too much.”

Then he walked away in the other direction, hands in his pockets. We watched him go. He turned the corner at the end of the street and that was, I think, the last time we ever saw the magician. You remember right? Come on, you remember? It’s okay, you can tell me. You can admit it. I don’t begrudge you.

I don’t begrudge you however many years you have, however many years more than me. It’s quite alright. I don’t mind. It doesn’t affect me at all.

Joseph Sparke is a second-year English undergraduate at Gonville & Caius College.