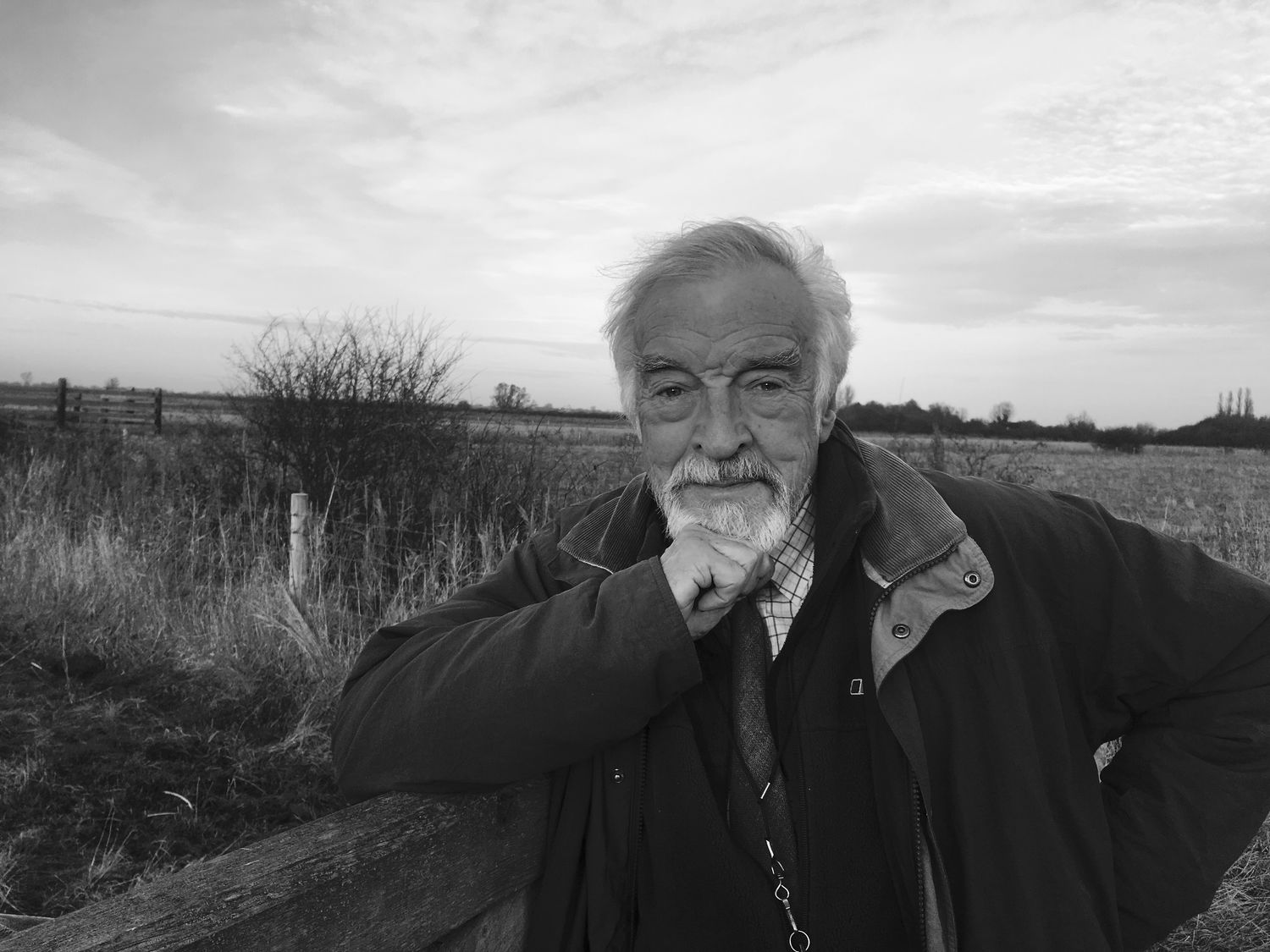

Dr Charles Moseley came to Cambridge as an undergraduate to read English Literature at Queens’ College in the ’60s and never left. Needless to say he knows the Cambridgeshire countryside pretty well by now. Author, teacher, scholar and Life Fellow of Hughes Hall College, he remains one of the most knowledgeable, but more importantly one of the kindest people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting during my time at University.

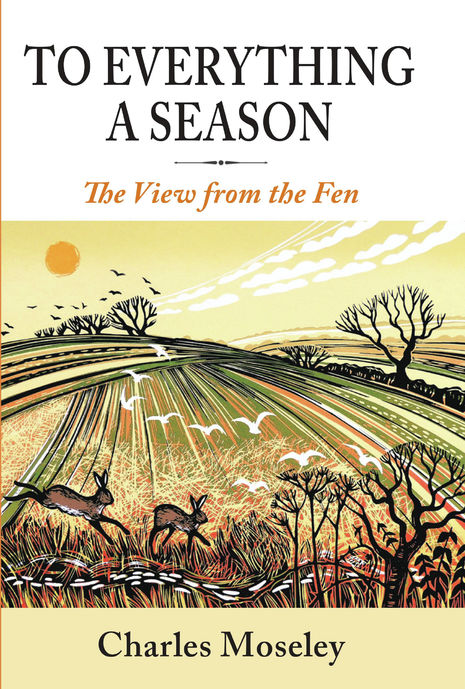

On discovering he had published not only one, but two new books, I sat down to talk to Charles about his writing process, and everything there is to know about his ode to life in the Fens, To Everything a Season.

I was firstly interested to know what Charles’s inspiration was for writing this book, which he describes as “A collection of jottings, impressions, delights, some made up decades ago, some just yesterday.”

To this, he replied that the first lockdown “was a marvellous opportunity to think about all sorts of things, but it was also an exceptionally beautiful spring. And I found myself writing some notes about what I’d seen and, of course, that sparked off memories about what I’d seen years and years and years ago, and before I knew where I was I’d got a book.”

“Look at things closely and be patient. And before you know it, you’ll end up seeing differently as a habit”

“It really did almost write itself.” Charles went on to add, his passion for writing evident on his face, “I’ve always had this love affair with the English countryside. I am appalled at what has been done to it and is being done to it. It’s a much less rich countryside than it used to be. But still, there is so much beauty there, if only you open your eyes and just have a look. Look at things closely and be patient. And before you know it, you’ll end up seeing differently as a habit, and might even end up with a book.”

Easier said than done. However, Charles’ description was so heartfelt and honest, that for a second he had convinced me that, despite my better judgement, perhaps writing a book could be rather simple after all.

“It is also quite seriously a meditation on time and ourselves in time,” Charles went on to add about To Everything a Season. “There are some bits in here that I think are quite funny, because life can be a bit comic at times, often when you least expect it to be. So that’s where the book came from. The real meat of it, of course, has been gathered over many years.”

Charles went on to tell me how he originally came to Cambridge from Lancashire which he describes, quite differently to Cambridge, as “hill country”. Except when he lived in central Cambridge as an undergraduate (he has lived for years in Reach) Charles has never lived in a town in his life, describing himself as unequivocally a “countryman”.

I was curious if he knew then that Cambridgeshire would become his home. “Not for one minute” he said, describing himself then as still in his “salad days”; He went on to comment, “One never even thought about tomorrow when I was an undergraduate; you started thinking about tomorrow in your third year: and then I started to think ‘I need to get a job’, and the first job I got was in Cambridge and I stayed there ever since”.

I then remarked that he must like it here, to which he replied, “Well, when you grew up in West Lancashire as I did, and you came to Cambridge you found it the most beautiful place you’d ever seen. The other lovely thing about it, is that for the first time in one’s life, I was in a group of people, the majority of whom – how do I put it? – were interested in, cared about, the same sort of things as myself, and that was just like-”, here Charles broke off.

“Like a gift?”, I asked.

“It was like a gift,” Charles replied, “it was a wonderful experience.”

“I’ve always found that books sort of grow rather like plants”

On his writing process Charles used a poignantly pastoral comparison saying that, “I’ve always found that books sort of grow rather like plants – academic books you have to plan, obviously – but when you’re writing for yourself, like I am here, they find their own structure.”

I know you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but the cover of To Everything a Season, – by Rob Barnes – is exceptionally beautiful. Charles noted that it was intended to capture all the seasons at once, and it does just this, and matches perfectly to the Eric Raviouls engraving at the head of each chapter .

On the seasons, I asked if Charles has a favourite, or one that is particularly meaningful to him: “Well, you remember in Coleridge’s Frost At Midnight?” he asked me expectantly (I didn’t have the heart to tell him that I didn’t, so I am ashamed to say that I nodded instead.) He continued and quoted from the poem, “All seasons shall be sweet to thee.’ Well, my favourite season is always the one I’m in at the moment.” Charles answered.

Finally I was most interested to know if there were undergraduate tales Charles would share with me, and it seems his mischievous and often jovial writing style is, in part, emblematic of his time spent completing his undergraduate degree.

“We had to be in at 10pm, unless we had a late pass, so most people knew how to climb into college with relative safety”

“Well, we got up to quite a few hijinks, nothing particularly personal, but I did climb into college quite often,” Charles remarked. “We had to be in at 10pm, unless we had a late pass, so most people knew how to climb into college with relative safety. In Queens’, for example, you had to straddle the spiked high railing over part of the river, which was a bit difficult but okay for the long-legged!”

He then described telling this story to a group of visitors to the university, and how there were one or two elderly ladies there, one of whom, upon hearing his story, apparently told Charles, “I would have you know that I climbed out of every College, dear boy, and then my young man got a Fellowship, and a key, and it was never as much fun!”: a daring feat indeed.

Of his university days, Charles said they were “Just like now: one had essay crises, extraordinary conversations until 3 in the morning, we thought we were being terribly clever and terribly philosophical, and probably we were talking rubbish. But it doesn’t matter. It was fun. It’s all part of growing up.”

“[Amazon] are sharks! I don’t think any more money should go to them”

On his newest books, he commented that “Nobody unless they’re dead lucky makes much money out of writing”. But he is determined that anyone wishing to purchase a copy of one, or both, or his newest works should do so in a bookshop; on Amazon he says “they are sharks! I don’t think any more money should go to them”. Instead, he encourages readers to support bookshops, otherwise there “won’t be any bookshops left”.

I think my takeaway from my discussion with Charles, despite being, or so I thought, pro-city my entire life (a far cry from the slow-moving Norfolk countryside where I would visit frequently with my family as a child), is that there’s a lot we can all stand to learn from Charles Moseley’s way of life. To slow down for once, be patient, and just stop to truly appreciate the natural world, could really help us to cherish everything more, throughout the seasons.

Charles has not only one but two books out: ‘To Everything a Season: The View from the Fen’, and ‘Crossroad: A Pilgrimage of Unknowing’. They are both available in all good bookshops, and online.