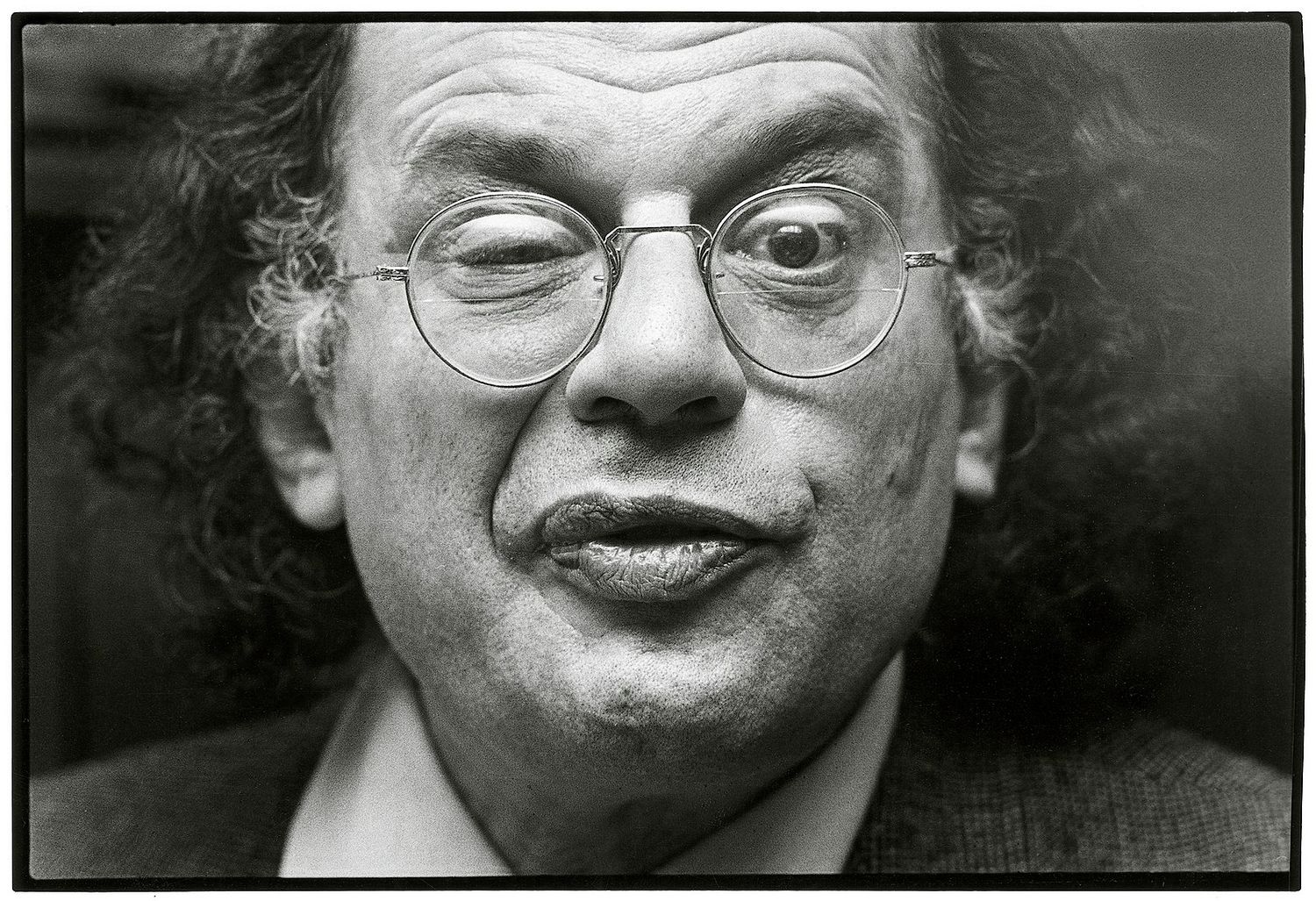

This April, it will be 25 years since the death of Allen Ginsberg. After a lifetime of intoxicating habits, he eventually succumbed to liver cancer. As he lay inert in his East Village bedroom, he was visited by a number of great artists representing the full range of 20th century American genius. Roy Lichtenstein, Patti Smith, and junior Beat Gregory Corso — all titans in their own right yet dwarfed by the poet on death’s door. For Allen Ginsberg was almost solely responsible for the new age of American literature and culture that had come forth during the 40s and 50s. He had changed the tide, contributing more significantly than any other poet to the counterculture of the period. His work was abrasive, intimate, offensive, heartfelt, and undeniably him.

“But he was a man who made mistakes – he was cripplingly, wonderfully human”

When I was sixteen I read his poetry, and then the seminal biography on him by his friend and archivist, Bill Morgan, then his poetry again. Very few books have had an impression on me comparable to that biography. Especially the account of his university years, which echo around me every day that I am at university and counterpoint my own experiences. Allen was born in 1926 in Newark, New Jersey, but grew up near Paterson, a point of connection with his future poetic mentor and inspiration, William Carlos Williams. His artistic mantra, “no ideas but in things”, Allen later adopted as his own. In 1943 he graduated high school and began attending Columbia University in New York City. There he met a group of men that were to become and remain some of the most important people for him: Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs. They formed the nucleus of the Beat movement.

Beat — coined by Jack Kerouac, meaning tired and beat-up or, according to Allen, deriving from the word beatitude — was a movement that formed and developed in, mainly, New York and later San Francisco. The Beat literary style is mostly formless, spontaneous, and influenced by the freeness of Jazz. Allen, the lynchpin of the Beat writer group, wrote with the utmost Beat-ness. His most famous poem, Howl, published in 1956, shocked and repulsed the world. So much so that in 1955 the U.S Customs Department confiscated 520 copies of the poem that had been printed in the UK on grounds of obscenity. A trial ensued, with Allen’s publisher and friend, fellow founding father of the Beat literary movement, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, facing obscenity charges. He was defended by the ACLU and was eventually found not guilty.

“His work was abrasive, intimate, offensive, heartfelt, and undeniably him”

Howl is obscene. It’s graphic, visceral, and uncomfortable. But it’s also poignant, poetic, and true. It’s both a love letter and an elegy. It focuses on the sordid world he lived in and the troubled characters that surrounded him. Other than being a fantastic poem, the Howl trial was colossal in the fight for free speech and artistic autonomy. Allen’s belief in the freedom of speech was something that he defended tirelessly throughout his life; he protested against the Vietnam War, pushed for gay rights, and travelled to many communist nations to promote free speech.

He wasn’t spotless, though, so while I admire him for many reasons, there are some uncomfortable truths about Allen Ginsberg. Citing the importance of free speech, Allen was a member of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), an American paedophilia and pederasty advocacy organisation. Of course, the real motivations behind his membership of NAMBLA have been debated, with many people viewing his ‘free speech’ spiel as a red herring for a much more insidious predilection. He also had an immense sense of self and an incredible ego that paradoxically coexisted with his many neuroses, insecurities and perceived deficiencies. Further, he was an unhealthy life-long partner to Peter Orlovsky, who was largely dependent on Allen – a dynamic that Allen created and perpetuated. Allen valued the male relationships in his life to an illogical degree, and largely ignored women; he was apathetically sexist.

"Howl is obscene. It’s graphic, visceral, and uncomfortable. But it’s also poignant, poetic, and true”

However, he was, like any great artist, his art. None of his work captures his essence so completely as Kaddish. As the name suggests, Kaddish is a funereal piece, written after the death of Allen’s mother Naomi in 1956. She had been mentally ill for the duration of Allen’s life and had influenced and traumatised him in innumerable ways. They had a strained, complicated relationship, which in turn affected Allen’s subsequent relationships with women. Kaddish is biographical, a panoramic view of Naomi’s life before and with Allen. It’s deeply personal, with countless references to people and places that would be known only to the Ginsberg family. It’s long, and by the end of my first reading of it I felt a tremendous sense of loss, like Allen had conferred his grief over his mother onto me.

His identity, interests, and styles underwent various transformations between the 40s and the 90s, reflected through the variety of his work. He was a man capable of learning new things and changing, metamorphosing from the influence of the people and places he experienced. He was fiercely loyal, too, almost to a fault. For the entirety of his life, he recognised the importance of the men who had made him in his Columbia years. What strikes me most about Allen Ginsberg when I survey his life and work, is the sense of becoming that is so potent in his diaries and poetry. He was never just one thing, he never constructed his entire self around one identity or one cultural influence. He was constantly expanding, changing, challenging himself. But he was a man who made mistakes. And that’s why he’s my favourite poet — he was cripplingly, wonderfully human.