‘There are two motives for reading a book; one, that you enjoy it; the other, that you can boast about it’, said mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell. In many ways, he’s exactly right. Finishing a book comes with a sense of accomplishment you simply do not get from completing a binge of the latest Netflix show, or scrolling through 2 hours of TikToks. But what differentiates books from these other forms of media that cry out for consumption and approval? My suggestion: the narratives we create around the ones already contained in novels, and the demand they place on the reader. Rather than passive inhalation of a storyline, where the burden of content formation is placed on the creator, novels are fundamentally interactive, as everytime a reader opens a book, she inhabits a conversation between herself and the writer.

This is not to say that films and TV shows are not also dialogic, but to build a world from words requires so much more creator/consumer collaboration. Authors require us to engage, to imagine what characters and settings are like, to question intention, and decipher as much from what is not said as from what is said. In this way, what I love about sites like Goodreads is their ability to transpose this experience into the public domain, and give us the tools to show what it means to be an active and critical reader.

“The more I shared, the more the books I read felt alive, and Goodreads was where I replied to the message the author had left me”

But I have not always felt this way.

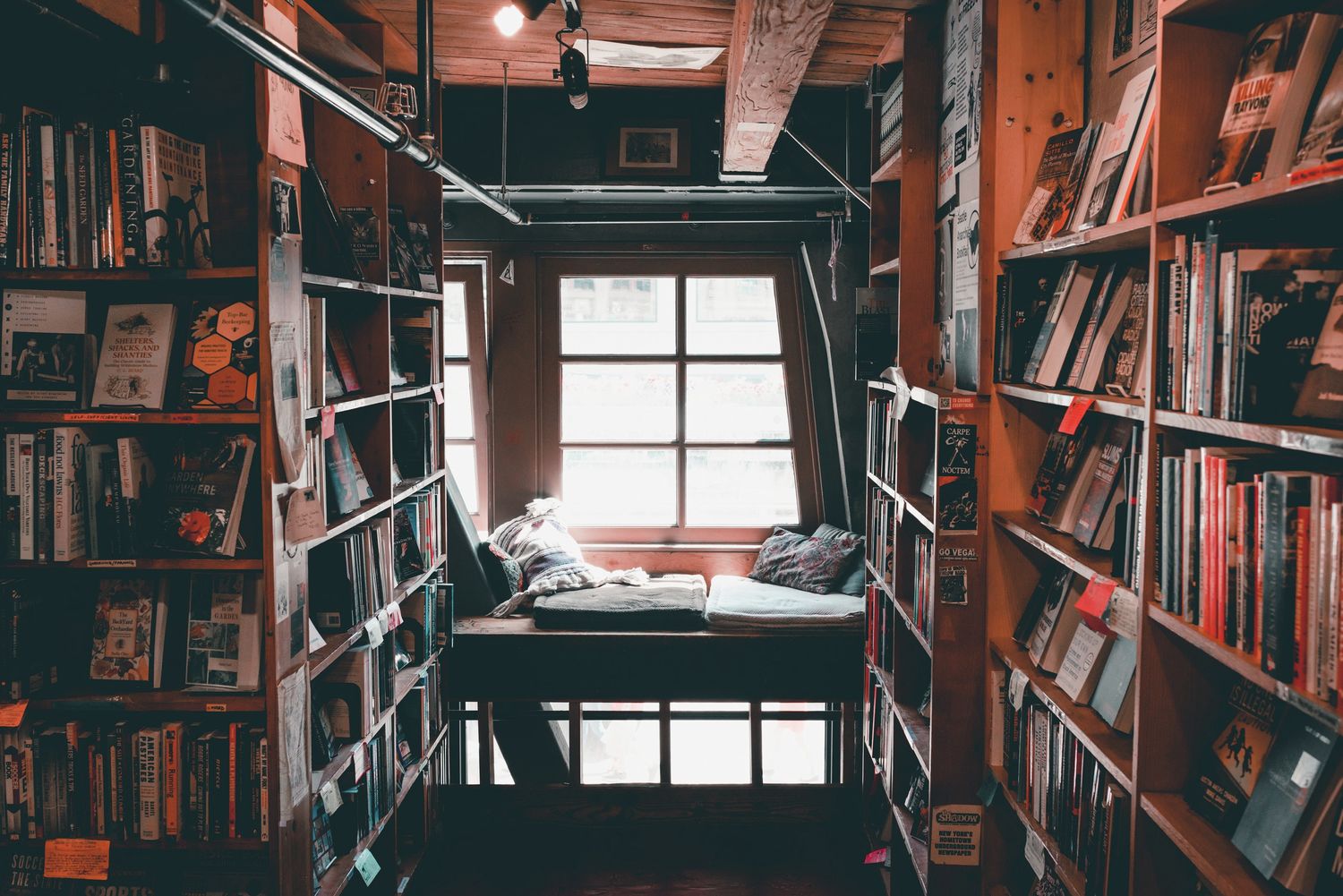

Goodreads is an online platform that allows its users to search for books, leave reviews, and spy on the literary habits of friends and family. One key feature of the social library is the ‘reading challenge’ you can set for yourself each year. How many books will you read in 2022? One a week or one a month? More or less than your friends? Is this the year you turn from a YouTube junkie to one of the tote-carrying, Penguin-classic-reading elite? Some may object that such a feature is ultimately performative, shifting reading from what was the private pastime of a literate few to another form of social credit, but every year I am once again drawn into the promise of a new dawn. New Year’s Day finds me staring optimistically at my bookshelves, vowing with eyes shut tight and mouth set in a steely line of determination, that this will be the year. The books I compulsively buy at Waterstones will finally be read.

It's time! Join the 2022 Goodreads Reading Challenge and track progress towards your reading goals! How many books 📚 will you be pledging? https://t.co/SrWCgEQolG pic.twitter.com/uRMeIHaRD8

- goodreads (@goodreads) January 3, 2022

Every year I fail.

I felt like Goodreads was ‘shaming’ me, my supposedly ambitious reading challenges paling in comparison to my friends’ herculean efforts. Maybe it was the fact that studying at Cambridge had warped my relationship with reading. Before university, books were located within the ‘leisure’ category. I devoured the Malory Towers series, read Percy Jackson until I was dreaming of satyrs and centaurs, and consumed the Divergent trilogy as if it were the elixir of life. But at Cambridge, reading became work, and reading lists were sometimes burdensome (realising the last several pages of an article I need to read are wholly taken up with footnotes invokes tears of joy). After a hard day at the library, the last thing I wanted to do was see another word printed on a page. Mindless television, here I go. But everything has its limiting factor, and over the days I became increasingly restless, unfulfilled by the worrying amount of Made in Chelsea I was watching, and turned back to an old friend, with the help of a new one.

“The definition of ‘well-read’ I find most compelling now is not how much you read, but exactly what it says on the tin: how well you read”

It all happened this Christmas vacation. Finishing Toni Morrison’s Beloved left me in a state of bewildered despair, but I felt I needed to respond somehow to what I had just read. I needed to write something, anything, that would be a declaration to the world of the encounter I had with the novel’s poetic genius, the confusion and anger I felt at this record of human suffering and tragedy that Morrison had laid before me with no easy answers.

That response ended up being a Goodreads review.

After that, it was like the books on my shelves had caught alight, and I was trying to read every one before they began to burn. I finally finished Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, a wry look at college freshman Selin’s first term at Harvard, which had been sitting on my bedside table for months. I cried at the heart-wrenching intertwining narratives of Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, and cringed at the awkward prose (in my opinion, sorry to her fans) in Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing. I felt myself falling back in love with novels because I learnt one simple thing. The more I read, the more I enjoyed. The more I enjoyed, the more I wanted to share. The more I shared, the more the books I read felt alive, and Goodreads was where I replied to the message the author had left me.

Still, at times I feel like I don’t read enough, or that what I do read is not up to intellectual standards, but slowly my relationship with books – and Goodreads – is transforming. The definition of ‘well-read’ I find most compelling now is not how much you read, but exactly what it says on the tin: how well you read. Do you read with an open mind, an open heart, and open hands? Do you read with empathy and critical imagination? Then you are well-read. No matter what you read, or how much, these are the attitudes that make reading a joy, and literature a privilege.

I understand how some may think that posting about your reading habits, and writing carefully crafted reviews for the social approval of others, constitutes the height of pretension, but for me, Goodreads actually lends itself to combatting these elitist narratives. No longer is literary criticism the prerogative of the London Review of Books, or the ivory tower of a university English faculty, but every individual has access to a platform that enables them to voice their opinion. I can give Twilight four stars, and The Handmaid’s Tale two. I can baulk at a scathing review of my favourite book, or puff with anger that someone loves what I believe to be the worst-written novel in the world. What ‘good’ novels tell us, I think, is that voice matters, and Goodreads is aimed at giving us the tools to find our own.