Cosmic swirls of ink, flame-throwing winged creatures and eerie, headless female divinities vie for attention in the work of contemporary artist Shahzia Sikander. Born and raised in Pakistan, Sikander received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the National College of Arts in Lahore in 1991, where she studied the art of Indo-Persian “miniature” painting – viewed by many at the time as an outdated craft suitable for the tourist market.

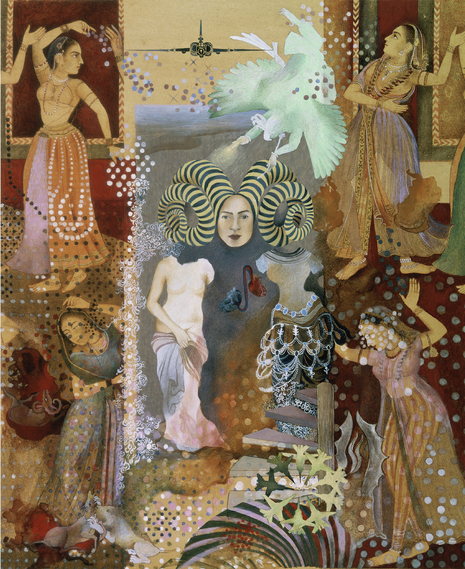

From this grounding in tradition, over the next three decades, Sikander has taken flight; through the integration of historical techniques with contemporary issues surrounding race, gender, sexuality and religion, her work challenges mainstream historical narratives and seeks to destabilise mechanisms of power left over from colonial legacies. For me, it is her unique fusion of the rich visual tradition of ‘miniature’ painting with symbols of modernity that is so captivating. In one of her most famous works, Pleasure Pillars (2001), created in the weeks following 9/11, a fighter-jet soars above a Graeco-Roman Venus and a Southeast Asian celestial dancer, imbuing their beauty with fragility and tension.

I use ‘miniature’ here in inverted commas; increasingly artists and scholars like Sikander are moving away from the term tied to its colonial associations. Such a label, in reducing an entire genre to its size, ignores the complexity and multitude of technical and iconographical aspects that constitute the tradition.

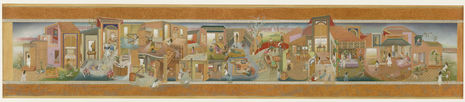

Sikander playfully problematises the term in works like The Scroll (1989-90). At the grand scale of 13 x 35.25 inches, Sikander literally and metaphorically expands the ‘miniature’ in this painting.

Not only the scale of the work, but also the subject is innovative; a woman, rendered in white, is repeated throughout the painting – Sikander herself. The architecture, based on the artist’s teenage home, serves as the stage for this semi-autobiographical chronicle. As the ghost-like protagonist engages in domestic tasks, we never see her face – an homage to the difficulty of discovering one’s identity as a young woman under the restrictive military leadership of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, which dominated Sikander’s time at the NCA.

“I was not interested in glorifying the past with nostalgic reconstruction, so I kept the focus on creating The Scroll as a forward-looking work.” (Interview with Rafia Zakaria)

Nevertheless, Sikander makes a point of maintaining tradition in The Scroll. The painstakingly detailed style, medium and architectural setting all call to mind Safavid manuscript painting. As the artist herself explains, through this deliberate evocation of the past, she was “seeking to link miniature painting to a pictorial tradition earlier than colonial history, connecting it to the Safavid tradition in an attempt to step outside of the coloniser and the colonised paradigm”. Tired of art historical narratives that excluded a rigorous understanding of South Asian art and female perspectives, Sikander uses her practice to carve out her own place in the canon.

Made more than 30 years ago, Sikander’s The Scroll also appears to intuit much of the scholarly attention that is now being devoted to scroll paintings by leading art historians such as Dipti Khera and Pika Ghosh. ‘Continuous Page: Scrolls and Scrolling from Papyrus to Hypertext’, edited by Jack Harntell, is one such endeavour that spotlights a rising interest in this medium.

Luckily for those of us in Cambridge, Sikander’s work is making its way to the university next year for an exhibition at Jesus College, starting in 2021. I discovered her works only recently while working as an assistant curator for the show, and in light of recent events across the globe, they certainly offer food for thought.

Fatima Mernissi (2018), which will be included in the exhibition, touches on a recurring motif in Sikander’s work: the veil (hijab). A sartorial choice and a symbol of modesty, in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attack, the veil has often been cast unjustly as a mark of oppression in European and American media. Indeed, President George Bush’s expression of concern for ‘women of cover’ became a key justification for U.S. intervention in Afghanistan in 2001 – to ‘liberate’ these women.

The Taliban’s recent de facto takeover of Afghanistan brings these concerns back into focus. Now more than ever Sikander’s work reminds us of the veil’s potential to carry a deeper and more nuanced symbolic significance. In this portrait of Moroccan feminist writer and sociologist Fatima Mernissi (1940-2015), the veil reminds us of the selectivity of mainstream historical narratives in its ability to simultaneously conceal and reveal – who writes these histories? Whose stories are left untold?

A further focus of the upcoming exhibition is decolonisation – in particular, decolonisation as an ‘act of love’, as told by her first work in sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020). As in Pleasure Pillars, Sikander again portrays an unexpected encounter between ancient divinities from different cultures; A Graeco-Roman Venus, based on the Italian Renaissance painter Angolo Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (c. 1545), gazes lovingly up at a divine Hindu dancer, inspired by a twelfth century Indian sculpture. Reimagined in this sensual embrace, the two female divinities embody what Gayatri Gopinath terms a ‘queer optic’ (Gayatri Gopinath, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora). Sikander sifts through histories that traditionally repressed non-heteronormative narratives, using symbols of the past to visualise a more diverse future.

In recent decades, many Cambridge colleges have had to come to terms with painful histories. Jesus College itself is undergoing a Legacy of Slavery Inquiry that has led to the return of a looted Benin bronze cockerel to Nigeria and the removal of college monuments celebrating Tobias Rustat, a donor of the college with significant involvement in the seventeenth-century slave trade. Sikander’s work offers us an alternative, more constructive way to engage with these legacies – through positive ‘acts of love’ rather than the negative toppling of monuments.

Coping with the past undoubtedly entails challenging existing symbols of power. But Sikander’s work invites us not only to look backwards, but to engage with tradition as a toolbox with which to construct the future.

Shahzia Sikander: Unbound is open to the public at West Court Gallery, Jesus College, on October 16, 2021—February 18, 2022. It is supported by the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Centre of Islamic Studies, University of Cambridge, and the Bagri Foundation. A parallel exhibition runs at Pilar Corrias Gallery, London, October 12 – November 13, 2021. Shahzia Sikander: Unbound is curated by Dr Vivek Gupta, Postdoctoral Associate in Islamic Art with the assistance of Cambridge History of Art students Milly Duckworth, Giacomo Prideaux, and Zoe Turoff.

For details of the exhibition: https://www.jesus.cam.ac.uk/articles/british-debut-shahzia-sikanders-promiscuous-intimacies-west-court-gallery