Hidden away in an enclave of Ely’s monuments, the enduring cathedral is a stained-glass museum, filled with both medieval and modern artefacts which preserve moments and figures in time, coloured by their contemporary cultures. During my visit, I found myself slightly spirited away by the glassy colours which reflected off the cathedral’s walls, tracing the same tracks as long-gone Cambridge fellows and religious folk alike. It’s certainly a whimsical feeling being there – and there’s an overarching feeling of listlessness which I’m still attempting to place. Retracing my own memories of the place feels almost predestined, as the very act of preserving memory or story in glass is exactly what the art form wishes to achieve. In my view, the museum certainly achieves this, and sheds its veneer as solely a religious craft and notion.

“Changing colours are in themselves a changing story, and often carry connotations that cannot be explained away with words.”

Stained glass making as an art in modern circumstances is certainly overlooked – and criminally so. Its associations lie with medieval or gothic notions of idolatry; however, I think its greatest purpose is presented through its ability to encompass and portray stories with singular images. Despite being a stationary art – the adjective ‘stained’ itself implying an inability to alter it – there is something inherently dynamic about stained glass. Its relationship with light for example, which filters through the glass at different intensities, evolving throughout the day can bring attention to certain features and change the saturation of the colours. Changing colours are in themselves a changing story, and often carry connotations that cannot be explained away with words. I therefore find it no surprise that it was utilised so frequently as a storytelling device in a period where many had no allegiance to words.

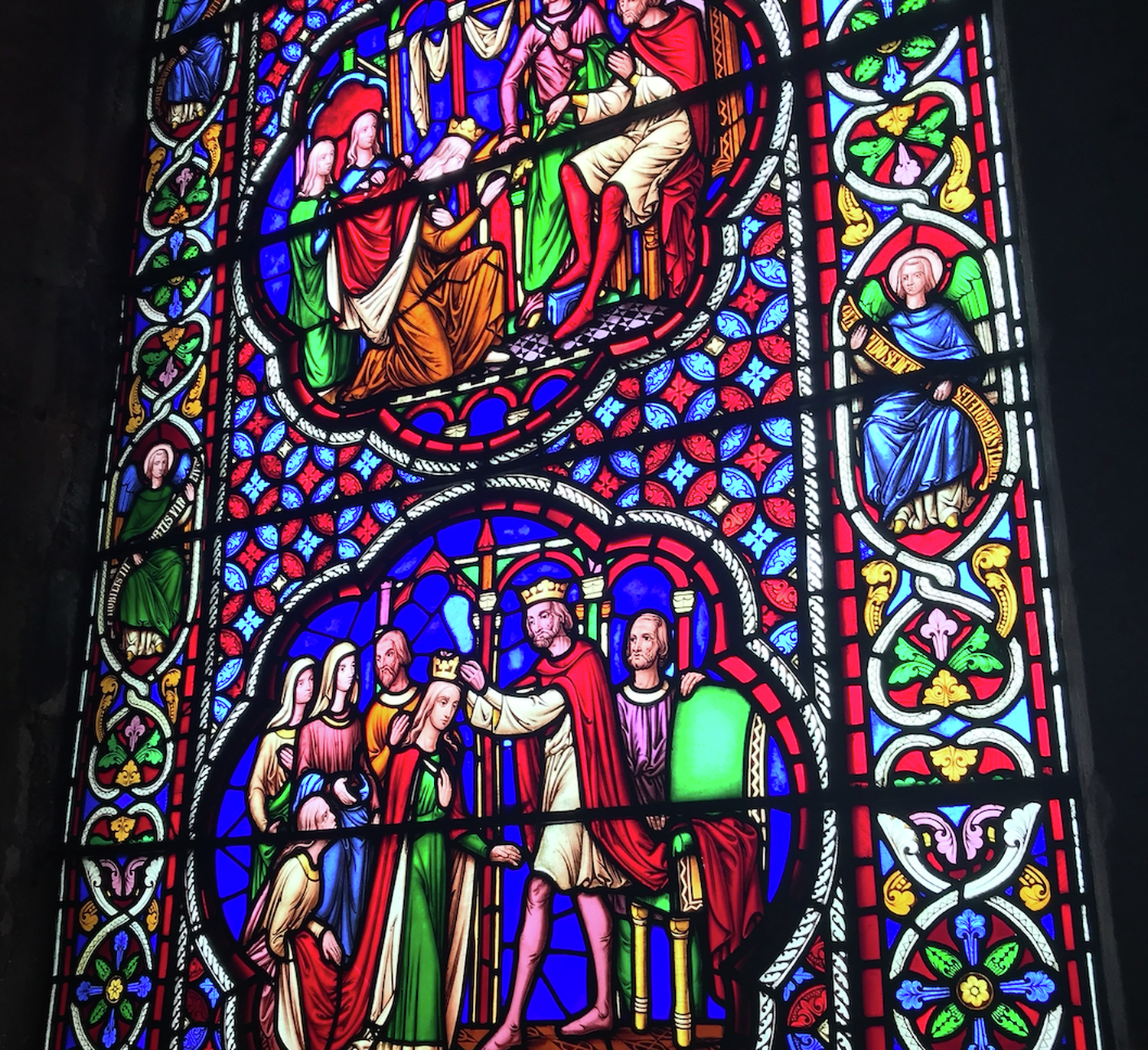

For instance, the painting below imagines a biblical scene frequently depicted by artists, that being Mary Magdalene’s reaction to Jesus upon his resurrection. According to John 20:17, Jesus uttered the resonant Latin phrase ‘noli me tangere’, which many interpret as his acknowledgement that the link between himself and humanity was forever severed. The phrase is absent from John Hardman Powell’s evocation of the scene, however, and his illustration implies a hierarchy without the need for words. Glowing in a vibrant gold, Jesus’ supremacy is palatable, contrasting the earthy green, blue, and red colours which characterise Mary and their surroundings. It is an ancient scene which Powell creates, and one of many iterations; it was of special interest to Renaissance painters such as Titian and Corregio. Yet here is this 19th century version, just as decorative, just as brilliant – and proof of stained glass’ unwavering ability to capture moments and stories in a medium often viewed as more physical and multi-dimensional than traditional painting.

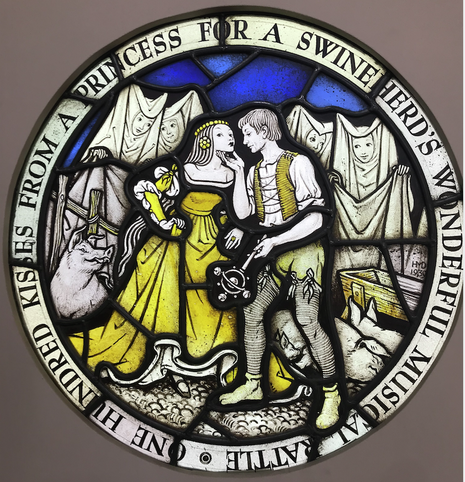

Aside from religious and royal figures, women were primarily the subjects of stained glass work, and scarcely the artist, following a pattern which has endured historically. Harcourt Doyle’s ‘One Hundred Kisses’ certainly objectifies the woman depicted; her ‘sweetheart’ holds her pouting face and pulls her inwards, into a somewhat submissive position. It’s suggested, however, that the man’s music – his ‘wonderful musical rattle’ – is what draws her in, the bell-like instrument firmly located in the centre of the piece. The woman’s face, despite poised towards him, is directed to the perceiver – her eyes met my own as if I were a mirror or a camera lens. There’s a feeling of connection, when you see these painted, unreal figures meet you in gaze. It is almost surreal. Like Powell’s clothing of Jesus, yellow is the colour which makes its home on her dress. I found this to be the case with many of the women featured – there’s a certain warmth to their images which really affirm their presence. And whilst many are objects of the male gaze, or are simply background figures, there’s a defiance in their characters which I really enjoy.

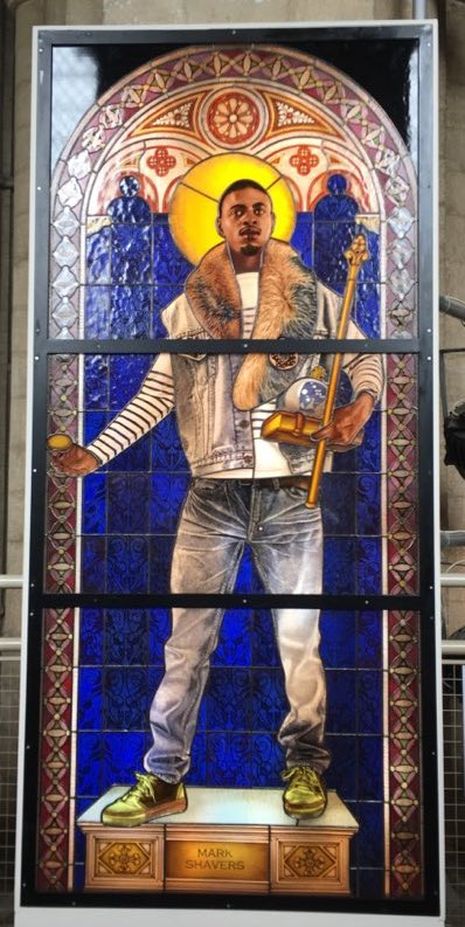

Naturally, biblical and kingly scenes are rife in the glass panels, depicting everyone from medieval kings to various episodes of Jesus’ life, all underpinned by the same range of colours, transparent and illuminated by the sun. Incredibly detailed, the museum showcases different iterations and styles of presenting these stories, taking both a timeless and a global perspective. With displays in chronological order, the immortality of the craft is tangible, and the diversity of the art is surprising. The half-way point of the exhibition is marked by a Black Lives Matter tribute, a feature I was completely taken aback by seeing. The artist had taken inspiration from a stained glass panel, replacing the previous figure with a black man, dressed in modern street-style and with golden shoes, holding a golden egg and sceptre. It is extremely beautiful, as well as exceedingly well-crafted, and makes a statement, tells another story, just by utilising an art form which almost exclusively depicts white people and their achievement. The stereotype of stained glass making being a bygone, outmoded craft is detached from reality. Like any fine art, it is used in the same way, to illustrate the important stories and elements of our time – ‘Saint Adelaide’ is joyful and celebratory. And what more important to highlight than the lives of black people, historically excluded from mainstream channels of art?

“There’s a feeling of connection, when you see these painted, unreal figures meet you in gaze.”

Leaving the museum, I began to contemplate the future of stained glass as an art form. From a friend’s mother taking classes, I was aware that stained glass making was making somewhat of a resurgence in popular culture. Scrolling through the stained glass hashtag on Instagram, it’s clear that many artists remain in business, making artisan displays for businesses, restoring old church and chapel window panels, and making affordable, everyday works accessible to most. As well as Kehinde Wiley’s innovations through his Black Lives Matter tribute, women are becoming recognised for being stellar stained glass artists. Like most strands of art, stained glass has a predominantly masculine history. Artists such as Annahita Hessami, who owns Glass Cut Studio in London, are demonstrating how the form is still in demand and can propel local business. Her work in progress, pictured here, reflects that the life-span of stained glass making isn’t over yet, and that there’s still far to go in our own discovery and appreciation of the craft.