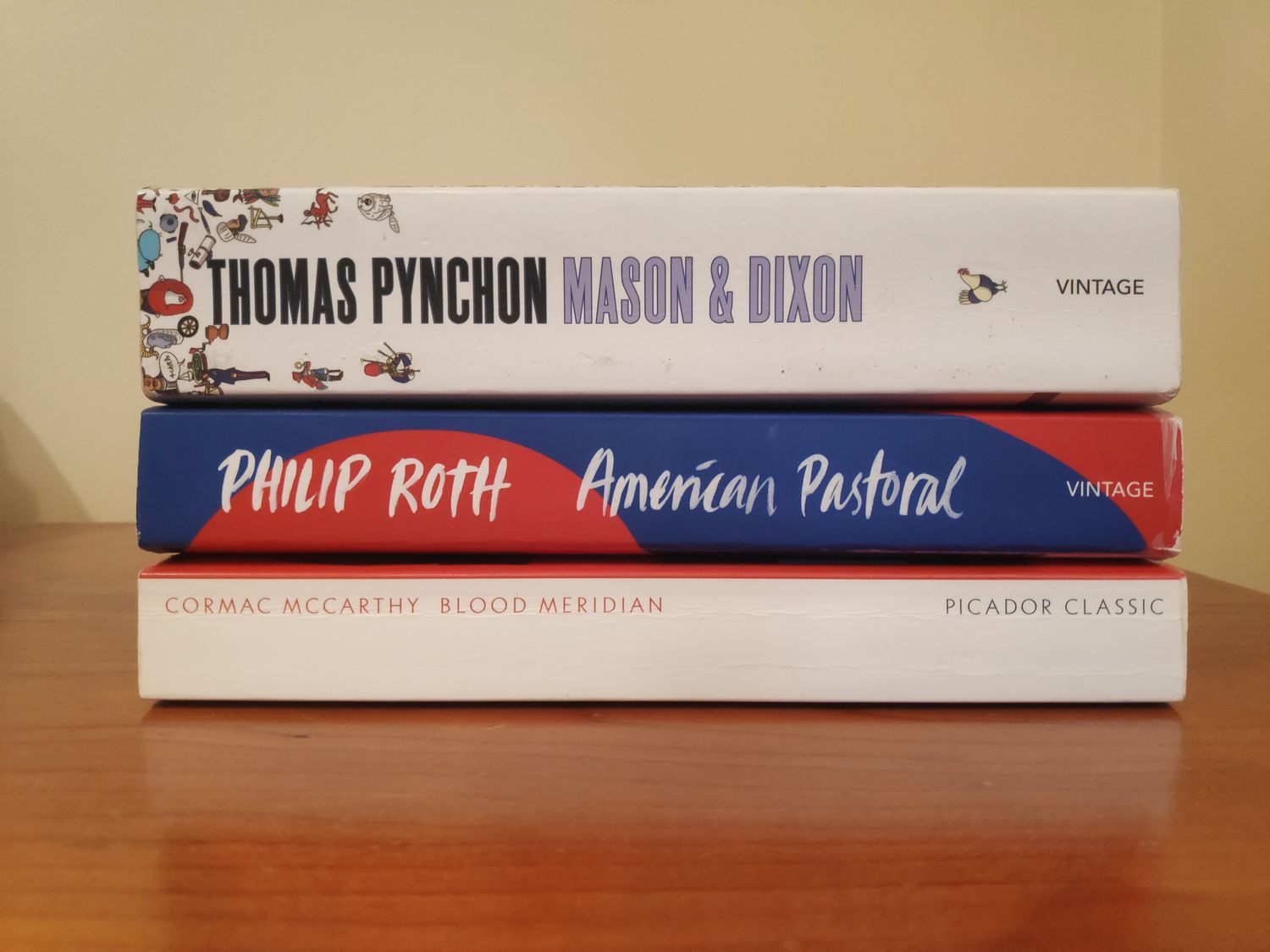

The world has just witnessed a tumultuous American election. Why we in Britain seem to care so much is a huge question, but part of the reason is surely the potential in American politics for true conflict – disputes with life or death outcomes that make British politics appear grey in comparison. Literature can tell us something about this. The critic Harold Bloom identified a number of modern works of fiction as being examples of the ‘American Sublime’. These are novels that achieve peculiarly American heights of beauty and profundity, and it can’t be a coincidence that so many of them are intimately concerned with violence. Three popular examples embodying this connection are Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon (1997), Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985), and Philip Roth’s American Pastoral (1997), which deal with American violence in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries respectively.

To start with Pynchon’s sprawling novel – Mason and Dixon, English surveyors tasked with drawing the American boundary line that would soon separate the north from the slave-owning south find themselves pushing westwards into ever wilder country, bereft of stable society. They are intrigued by stories of the ‘Paxton Boys’, Pennsylvanian militiamen who took up arms in 1763 (the year before the pair arrive) and slaughtered frontier Native Americans out of racial hatred and pathological insecurity. In a chapter at the novel’s spatial and thematic heart, Mason becomes overwhelmed by the senselessness of the violence attending the gestating nation and condemns the locals for their vulgar indulgences:

Acts have consequences, Dixon, they must. These Louts believe all’s right now,– that they are free to get on with Lives that to them are no doubt important,– with no Glimmer at all of the Debt they have taken on. That is what I smell’d,– Lethe-Water. One of the things the newly-born forget, is how terrible its Taste, and Smell. ... In America, as I apprehend, Time is the true River that runs ‘round Hell.

‘Lethe-Water’ and ‘the true River’ refer to the stream described at the end of Plato’s Republic, which, when drunk from, grants you the amnesia necessary to be reborn. America represented a promise of rational government and free citizens, but the vast continent provoked the most inhuman paroxysms from the settlers against those who were there before them. The only way to cope, Pynchon says, is to forget.

McCarthy’s novel picks up the expansionist story in the south. Again, Native Americans are hunted, this time in the aftermath of the 1845 annexation of Texas. But Blood Meridian’s themes are more universal. It portrays conflict as the main fact of human nature, something fated to return in every iteration of human society. This might not be an original insight, but the force of the book comes from the unrivalled carnality of McCarthy’s prose as he portrays violence committed for no discernible reason. His characters have no inner life, nothing resembling motivation. The ‘Glanton Gang’ of scalp hunters who traverse the frontier committing wanton acts of brutality are accompanied by ‘the judge’, a hairless apparition who speaks in riddles, possesses preternatural intelligence, and worships violence. His philosophy is that “war is god”:

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

As Harold Bloom put it: “We are a country that has had a kind of perpetual, ongoing religious revival since the year 1800, and simultaneously we have been completely gun-crazy for the last two centuries. And in some sense, that’s what McCarthy’s great book is about.” He invokes school shootings, domestic terrorism, firearm ownership. Clearly, America is so much more than that to Bloom and McCarthy. However, the job of the novel is to paint in biblical colours the subterranean potential for violence inherent in a continent as vast and strange as McCarthy’s vision of his own country.

Finally, with the United States’ borders set, Roth’s American Pastoral deals with civil violence during the fallout from imperial adventure in Southeast Asia. ‘Swede’ Levov, a proud homeowner who thinks he has achieved bourgeois domestic bliss, has a daughter who grows up to hate America, eventually setting off a bomb in protest against the Vietnam War. Roth displays an intimate acquaintance with the mind of a middle-aged man disgusted at the terribly sincere, hyper-virtuous, privileged, hypocritical student progressives of post-1960 America. Lazy right-wing emotivism doesn’t make you a good writer (neither does its opposite). Yet Roth does not fall into this trap. The enemy in American Pastoral is not the left. It is chaos: the state in which the conflict of value-commitments, emotional loyalties, psychological frameworks, and political affinities grows so loud that it becomes the most important social fact; it envelopes order and reason, which it reveals to have been no more than a mirage, so that you peel back the skin of chaos to reveal nothing but your own incomprehension:

Yes, alone we are, deeply alone, and always, in store for us, a layer of loneliness even deeper. There is nothing we can do to dispose of that. ... There is no protest to be lodged against loneliness – not all the bombing campaigns in history have made a dent in it. … Stand in awe not of Communism, my idiot child, but of ordinary, everyday loneliness.

Father against daughter, capitalism against communism. This is not the situation we are in today. But our politics represents a culture war, and it is the atmosphere of culture war that Roth distils and magnifies, even down to his suffocating writing style, which layers sprawling paragraph upon sprawling paragraph of hopeless reflection for dozens of pages on end. The claim is that in this, the postmodern chapter of Anglo-American history, as little as in the Age of Reason, nothing is insulated against the headwinds of anxiety, irrationality, and ultimately bloodshed. They always return to bite; especially, it seems, in 2020.

There is something ironic about writing from Britain about what America is ‘really like’ through the lens of literature. Nevertheless, while in this country we’re stuck with making outsider comments about political life over the pond, it seems that great fiction can at least give us some indirect access to the violent potential lurking beneath the surface of a nation struggling to live up to its ideal of itself.