“There was a time when it was enough for a woman to simply be at Cambridge”, reads a Varsity article from the 60s. When to be admitted into these hallowed halls (albeit the redbrick halls of Girton and Newnham tucked far away from the rest) was a satisfactory step in the right direction. But when the aforementioned article was written, there were still many steps to be taken. There still are today.

The piece from which this quote was taken finds itself neatly tucked away in the “Women″ section of the paper. Maybe once a necessary evil to ensure that editors didn’t entirely forget about the “second sex”, its assumptions about what would satisfy the appetite of its female readers were just about as narrow as the Mail Online’s Femail section remains today. For how could the fragile minds of women compute anything more serious than the latest trend forecasts or idle celebrity gossip?

“I failed to become the first woman editor of Varsity because I was in love with the Arts editor”

In Lent term of last year, as I sat struggling through another Early Modern supervision about women in theatre, my supervisor (as if to pitifully prove his woke superiority against the Renaissance men discouraging “whores” from the stage) regaled us with a story about his term as Varsity’s Editor in Chief. And how it was his brave, bold feminist action that removed the “Women” section from the paper. In the long run, it was probably a good call. As he explained, women should be represented in all aspects of the paper, not tucked away. But whether that was his decision to make remains an entirely different matter. Especially as he went onto explain how he calmed the outrage of women in his team by assuring them of all his feminist intentions.

In the early days of the paper, this division on the page quite simply mirrored the division across the university – there were women’s colleges and there were the rest. Reading about a time before my own co-educational college (Robinson) had spawned into redbrick existence, each new leaf I turned through the crumbling archives seemed to reveal new developments in women’s rights. In 1969, King’s agreed to admit women for the first time. The chairman of King’s Student Union commented: “I’m only sorry I shan’t be here when the first women arrive.” What a struggle it must have been for a heterosexual man to get laid, back in the day. However, some feminist progress required much more active protest. In October 1961 the Cambridge Union was “stormed [by] six fiery females [of the] Cambridge Union Suffrage Movement”, forcing the Union to finally offer female membership in the following year. According to Camfess, the “love-hate relationships between women and the Union” discussed in the 60s seems to still be alive and kicking today. You must either girlboss your way to the top or sickeningly roll your eyes from afar, while you protect your purse from those who insist the only way to defeat Union sexism is to buy your way into the fight.

But these bright sparks of progress I found were overshadowed by the sexism which reared its ugly head in most of the archival pages. In an interview with Gillian Cooke, the editor of women’s magazine Honey, rather than regaling readers with her admirable achievements, the paper introduced her as “a diminutive, cuddly woman, looking about twenty-five.” She “has been in journalism for sixteen years, after turning down an open scholarship in Maths to Oxford, but still bubbles like a schoolgirl.” All her academic prowess bursts in one bubbly prick of infantilisation. Good thing it’s her “sympathy” that makes her such a “good editor” – I will be sure to add that special skill to my CV when trying to enter the cut-throat world of journalism.

“All her academic prowess bursts in one bubbly prick of infantilisation”

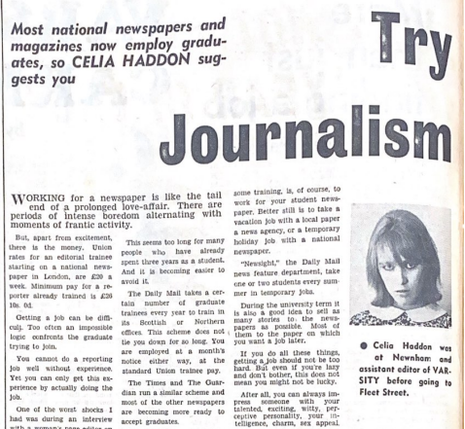

However, that didn’t stop some women from forcing the paper to take them seriously. Women like Suzy Menkes, the first female editor of Varsity in 1966, who went onto specialise in fashion journalism, writing and editing for publications such as the Times and Vogue. When I reached out to ask her if any part of her was reluctant or intimidated to join the paper as the first female editor she responded: “what a weird question! We were young and full of enthusiasm. We felt we had been selected because we were equal to – even better than – our male counterparts.” She exclaimed: “all your questions suggest a Shock Horror for all the poor females, miserably trying to compete with brilliant males. But it was quite the opposite. We had to work super hard to get into Cambridge – and as a result we felt strong and eager to do anything.” According to Suzy, sexism wasn’t “really seen as holding back women’s lives until the late 90s or the New Millennium”. Probably a contentious point for others in the era. Another female writer from the 60s, Celia Haddon, was an assistant editor at Varsity. When I reached out to her she told me that when she worked on the paper there “were ten men for every woman. I just took it for granted that this was how it was,” adding that in her “first job on the Daily Mail I was the woman reporter so that was no different either.” When being persuaded to join the paper she was told: “you will be invited to all the best parties” (I wish that were true today). But as she jokes: “actually in those days if you were blond and female you got those invitations anyway. There was such a shortage of females.”

Despite her insistence in an article from the 60s that graduates “try journalism”, over 50 years on, she tells me: “I think I just had a good time at Cambridge: I wasn’t really very ambitious. I got a job in journalism after leaving because the Mail decided they wanted a woman graduate”. Having now turned from journalist to professional cat expert, she seems to have found where her true interests lie. Back in the day, she apparently “failed to become the first woman editor of Varsity” because she “was in love with the Arts editor.” She tells me how one day when “in bed with him, somebody came with some copy and instead of getting up and dressing and going down, I simply said: ‘Come up’, and took the copy from them while still in bed!” Looking back, she realises: “that was too raunchy for some of my colleagues.” Yet another example of a woman’s struggle to the top defeated by the very wild idea that a young woman might enjoy sexual relations in her uni years. When I inquire into the sexism at the time, she says: “I don’t remember it – but then, I am a naturally noisy woman. There were no predators – unlike my first year on the Daily Mail which was eye-openingly horrible.” Giving me a “taster” of the Mail she reveals that the assistant news editor would “put his hand down my top in front of every one to humiliate me” and “the subeditors (all male) used to ask me over to check the copy so that I would lean over and they might see my knickers (I discovered that 20 years later!)”.

“Apparently I wasn’t a terrible journalist; I was just treated as such”

Although Varsity may not have been anywhere near as bad as the Mail, the paper’s transition towards female leadership did not and could not overthrow the patriarchy entirely. It did not take away from Menkes’s own comments on the “long legs swaying in tight trousers or flashing between skimpy skirts” of girls as they pass by with their “shrill giggles.” It did not end Varsity’s Girl of the Week. Nor did it stop the paper in the 2000s from sticking one such girl on the cover, half-naked with the title: “Bottle up and explode! – Vian Sharif will pop your cork”. Varsity even projected the “giant 60ft image of the Daily Varsity covergirl” onto King’s College Chapel, in a wild publicity stunt much to the shock of “hundreds of passers-by”. Of course, she might have been entirely happy with her soft porn being projected for all to see, but it still feels eerily archaic in its blatant sexualisation. A sexualisation that continues today with egregious slips of the tongue (as the men would have you believe) about women opening their legs to climb to the top.

What was once the home of photoshoots and styling tips, the “Women” section has now been more appropriately named the Fashion section. When Varsity is under male editorship, Fashion is a section, along with Arts, that is often dismissed to the side in half a page, belittled, and unacknowledged. Especially when the section editors are women, as they often are. It was a surprisingly welcome breath of fresh air to see the women-led sections receive some double-page spreads by the female editors of my second term. Apparently I wasn’t a terrible journalist; I was just treated as such. I can only imagine the obstacles these women of the past had to overcome to feel respected by the men pulling the strings. Knowing what it is to see women’s words being twisted and ignored. Knowing what it is to feel your hard work going unacknowledged and unappreciated. As the paper has recognised for some decades now: “it is not enough for a woman to simply be at Cambridge.” As you enter the Oxbridgian world of hacks, politics and student journalism, you realise women don’t just deserve to be here. We deserve to be acknowledged, respected, and valued. Slowly but surely claiming male dominated spaces from the inside and making them our own. I may have accidentally become a “cover girl” - yes that’s me on front of the magazine - but now my words fill the pages of Varsity too.