She’s turning in the mirror, one arm bent and raised over her head. “Do you think I should stand like this?” I shrug, explain I have absolutely no experience when it comes to life modelling, and that she should just stand in the way she feels the most comfortable. Or perhaps the least cold.

Once a week, around 30 students sit down in various groups across Cambridge, to make sketches of nude models like Moya. The appeal is evidently broad: Corpus has recently begun their own life drawing society, and it’s a popular event amongst college Pink Week reps. Even the Union has been involved, holding ‘After Dark’ sessions in Keynes Library.

But the immense popularity of student life drawing is detached from the nudity. “It’s not about nakedness, but bodies as art in themselves: bodies as landscapes, with hills and troughs and soft edges.”

Moya is modelling for ARCSOC, the most well-known of the lot. The event will take place in an airy wooden room in the Architecture Faculty opposite The Mill; students routinely queue around the block to claim one of the limited spaces.

She tells me I’d find it relaxing. I know that I’d find it quite the opposite.

“She murmured a few small compliments before asking me if I wanted her to put it in the bin. Which, honestly, was fair enough”

Without really knowing why, I tell her about a city break I’d taken with a friend last Easter. We’d been out all day seeing the sights and had picked up some art supplies so we could spend the afternoon drawing. She loved drawing and was good at it, while I was just happy to get out of the sun.

The house was perched right at the top of a hill overlooking the river below – thick and dark, blotted with brightly coloured boats. I had an almost panoramic view of the scene, perfect for an artist. Across from me, my friend was merrily sketching away at an image of a woman, crafting cheekbones and lips and eyes just the way she wanted them.

I remember picking up one of the pencils we’d bought and attempting to draw the slow outward curve of the river’s far edge. There was absolutely nothing difficult about the task: draw a river, some boats, a few gardens, all slotted together in that pretty but uncomplicated way that man-made landscapes tend to be. The shape of the river even looked like a kid’s drawing, all symmetrical and S-shaped. But the pencil just wouldn’t travel where I wanted it to. When it did, the proportions were wrong. The boats were even harder, and when I managed to capture something that could pass a fair resemblance, I could never replicate it.

My friend had finished her drawing and asked to see mine. I remember handing her my sketch, searching the corners of my brain for a funny, disarming comment, to no avail. Flicking her eyes up towards me briefly, she murmured a few small compliments before asking me if I wanted her to put it in the bin. Which, honestly, was fair enough.

Some time after leaving Moya’s, I catch up with Rohan, a fresher at Newnham. The conversation turns to life drawing: they were diagnosed with ADHD in November, and tell me that attending life drawing classes at Cambridge has been an accessible outlet for their creative skills.

“I really enjoyed art at school but fell out of it during my gap year, just because I rarely found myself able to properly sit and sketch in a non-organised setting. With life drawing, everyone’s there, it’s kind of exciting because it doesn’t happen that often, and the model usually changes pose every so often to keep everyone engaged.”

Rohan admits that they’re not the best at art, per se, but tells me that’s not the point. “Everyone knows that drawing a body well is difficult, even if you’re naturally gifted. The time constraints mean that nobody gets more than a rough sketch in, so nobody’s producing masterpieces.”

Admittedly, the notion that I would be sitting in a room of professionals had put me off. I start to realise that my reluctance to join Moya at ARCSOC is rooted in fear, rather than inability.

“I’d worried that the atmosphere would be competitive, but I couldn’t have been more wrong”

The summer following that city break, I’d had a video call with a Disability Resource Centre for an educational assessment, to see if I fulfilled the criteria for adult ADHD. “Would you say you developed at the same rate as most of your peers?” she asked, pen poised. I replied that I had, apart from a few random things – struggling to learn to tie my shoelaces, taking ages to learn how to tie a ponytail. To this day, I cannot braid hair well, and I always have to double-check that my shirt buttons are in the correct holes. My other nemesis was touch-typing, which I never got the hang of at school. It was this last comment that caught the attention of the educational assessor.

“Have you ever heard of dyspraxia?”

I had heard the term before, but I wasn’t quite sure what it meant. Gently, the assessor explained to me that dyspraxia was a common disorder affecting movement and co-ordination, but not intelligence or concentration. In some people, it affects their social and organisational skills, while others might experience issues with fine motor skills like writing, typing, and drawing. The more I thought about it, the more I realised some of the issues I encountered didn’t fit the ADHD bill.

I found myself telling the educational assessor about my terrible drawing, and how disheartened I’d felt afterwards. She listened, then explained that my experience wasn’t unusual, or a symptom of any innate lack of creativity. Even though my form of dyspraxia was very mild and limited to issues with fine motor skills, it was still natural to feel frustrated and self-conscious when my body took longer to learn certain things. It was the first time that I hadn’t felt crazily oversensitive.

I bit the bullet. The first event I went to took place in Downing’s Heong Gallery, a long white room with oddly placed windows and one rectangular bench in the middle. My friend and I, along with around fifteen other people (mostly women) sat cross-legged on the floor in front of the bench, awaiting the entrance of the model. She came in wearing a long fur coat, which she casually shrugged off as she took up position. Then, everybody began sketching.

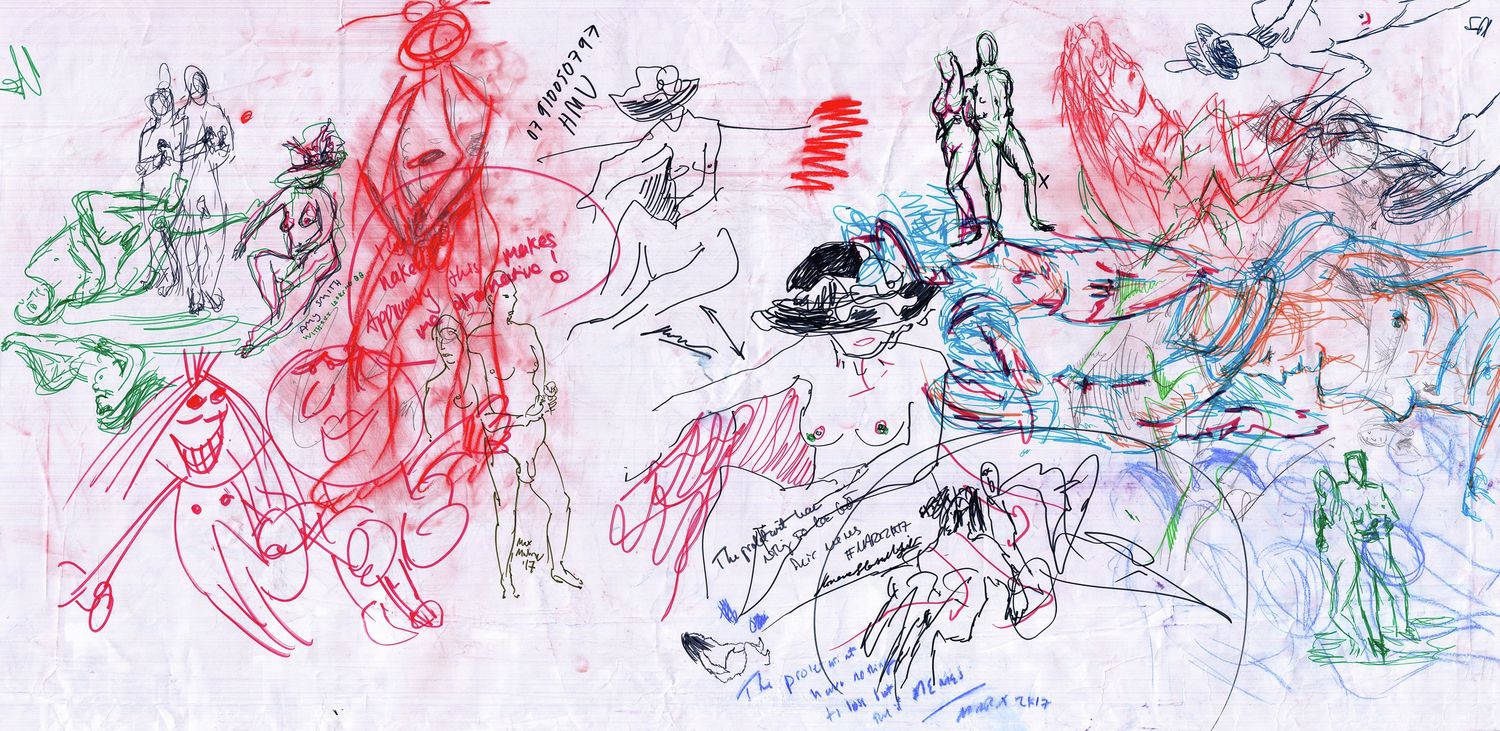

I’d worried that the atmosphere would be competitive, but I couldn’t have been more wrong. The organisers had set up some long rolls of paper for groups to draw on, so it was quite easy and natural to look at what other people were doing. I quickly realised that by observing others and copying their movements, I could produce something which actually bore a fair resemblance to the female form.

Gradually, she emerged – face, hip, shoulder – all more sophisticated shapes than the curve of a river, but quite doable for me if I drew in light pencil and kept a rubber close by. Of course, some of the other attendees were simply amazing, but there were a good few who just seemed to be experimenting, or who, like me, had been persuaded along by a friend. At the end, I felt surprised by how much I’d enjoyed what I’d assumed would be a painful experience, where anyone with a lower skill level than Edgar Degas would feel out of place.

“Modelling feels like a kind of ‘anti-objectification’, intentionally turning embodiment into symbolic meaning”

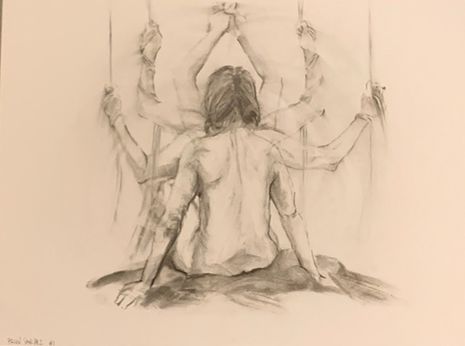

At one point during the session, I took a step back to regard the room as a whole. It struck me in that moment that real-life artistry remade the body as more personal and more abstract, all at once. Watching the outlines of a person take form in real time felt strangely transcendental, especially when it was being done by multiple people, all of whom had their distinctive styles. Around the room, drawings from past events were strung up. Contoured bodies in various stances, in drawings at various stages of completeness, danced across the walls. Very few had features to appraise, or eyes to look down. The model – she looked like everyone, and she looked like no one.

Afterwards, I chat to a few of my fellow attendees. Some, like me, are first-timers, others are seasoned life drawing veterans; all emphasise the positive effect that attending the sessions has on their body confidence.

For some, modelling feels like a kind of “anti-objectification”, intentionally turning embodiment into symbolic meaning. Others enjoy attending the sessions because they feel it celebrates the realness of bodies, without the clinical perfectionism of online visual culture.

The issue of accessibility is a common theme: all attendees recognise room for improvement. Notably, most life drawing events in Cambridge provide materials, opening up the sessions to those without means or previous experience. Some, like ARCSOC, charge entry to fund this, but with a ticket price of under £5 this is still more affordable than sourcing own materials.

Accessibility for the less mobile is a different matter: the Union’s events offer lift access, but other societies are a mixed bag. In many ways it speaks to a problem with Cambridge more generally, but many students emphasise that more efforts could be made by individual societies. Accessibility is often overlooked when organising events which are assumed to be self-selectively attended by those with existing interest and ability, so it’s important to draw attention to where improvements can be made.

I meet with Moya again about a week after this first session. She’s now well-versed with Cambridge’s life drawing scene, though from the other perspective. She tells me how exhilarating the modelling experience was, and how powerful she’d felt. I can’t help but ask her the perennial question: is it awkward?

“Everyone in the room feels awkward! Everyone’s slightly embarrassed. But that’s part of what people like about it. There’s some great music, there’s art materials provided, and people of all experience levels. It’s a very welcoming environment.” We’re walking near The Mill pub overlooking the Cam, very close to where she modelled, and we laugh about who felt more nervous walking in.

After she leaves, I sit down with a coffee and sketch the outline of the river.