A visit to the Wren Library on an ordinary day, to an ordinary person, would certainly be something to write home about: the library’s authority elevated on stilts, its imposing command over the scenes of the River Cam, its patient presence at the end of Neville’s Court. Looming stained-glass windows concentrate a rainy Saturday afternoon’s hazy sun rays through the clouds onto the chessboard floor, illuminating all that this university’s richest college has to offer. 400-year-old dust would not be enough to conceal the historical prowess of its collection of books, manuscripts and architecture, all accompanied by statues and busts of the likes of Sir Edward Coke or Richard Bentley.

“The celebration at this exhibition is a conditioned one, and must be distilled from any claims of purported historic progressiveness at Cambridge from those within the institution”

What then, if that visit to the Wren were to attend the opening ceremony for the Cambridge University Majlis’ Archival Exhibition, where all of the library-goers were suddenly adorned with saris and kurtas in their regal reds, greens and golds, muttering in Telugu or Punjabi or Urdu? And what then, if there were indeed very little dust upon the collections now on display: once-rejected, now-celebrated, unearthed and unveiled in their truth and glory, all telling a story of a prominent tradition of south Asian debaters, thinkers and activists at Cambridge since 1891?

I think you could easily imagine the splendid scene as one of ceremony, of education and of preservation. These three pillars stand tall to represent the dream of the recent committees of the Majlis society for the revival for a Society that once stood tall over Cambridge to a comparable degree as the Cambridge Union, especially spearheaded by Sara Saloo (m. 2019, Trinity, History and Politics), but founded of course by Mahid Qamar (m. 2017, Homerton, Land Economy) and Sahil Baid (m. 2018, St Catharine’s, Natural Sciences). World-inspiring previous members like Jawaharlal Nehru (m. 1907, Trinity, Natural Sciences, and no introduction required), Salma Sobhan (m. 1950s, Girton, Law, and the first Bengali female law professor), and Mohammad Hidayatullah (m. 1927, Trinity, Law and the first person to have been Chief Justice of India, vice-president of India and acting president of India), all serve to exemplify the breadth, activity and influence of the Majlis in the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, the first idea and naming of “Pakistan” was originally conceived in Cambridge, albeit controversially, by a Majlis member: Choudhry Rahmat Ali (m. 1933, Emmanuel, Law).

From this, sociologists such as Gayatri Spivak would note that it is unfortunate that the greats of recent south Asian history were largely confined to a Western, especially Cantabrigian, education in order to be able to speak for those in the subcontinent.

However, the exhibition addresses this form of epistemic violence appropriately, going only so far to accept the prominence of south Asian individuals at Cambridge in light of the hindrance that the Government and the British Raj imposed on the millions in the subcontinent who could not be afforded similar privileges. For instance, on display were letters exchanged between Lord Morley (lamentably the former master of my own college, Christ’s) and the Government’s Department for Foreign Affairs in the 1930s, that highlighted the cooperation most colleges had with prevailing British intentions to restrict south Asian participation in UK Higher Education. Clearly, the celebration at this exhibition is a conditioned one, and must be distilled from any claims of purported historic progressiveness at Cambridge from those within the institution – even if it did platform the poets, lawyers, diplomats, politicians, mathematicians, and activists that shaped so much of the last 100 years for the Brown community.

“This exhibition is still history-making just as much as it is history-keeping”

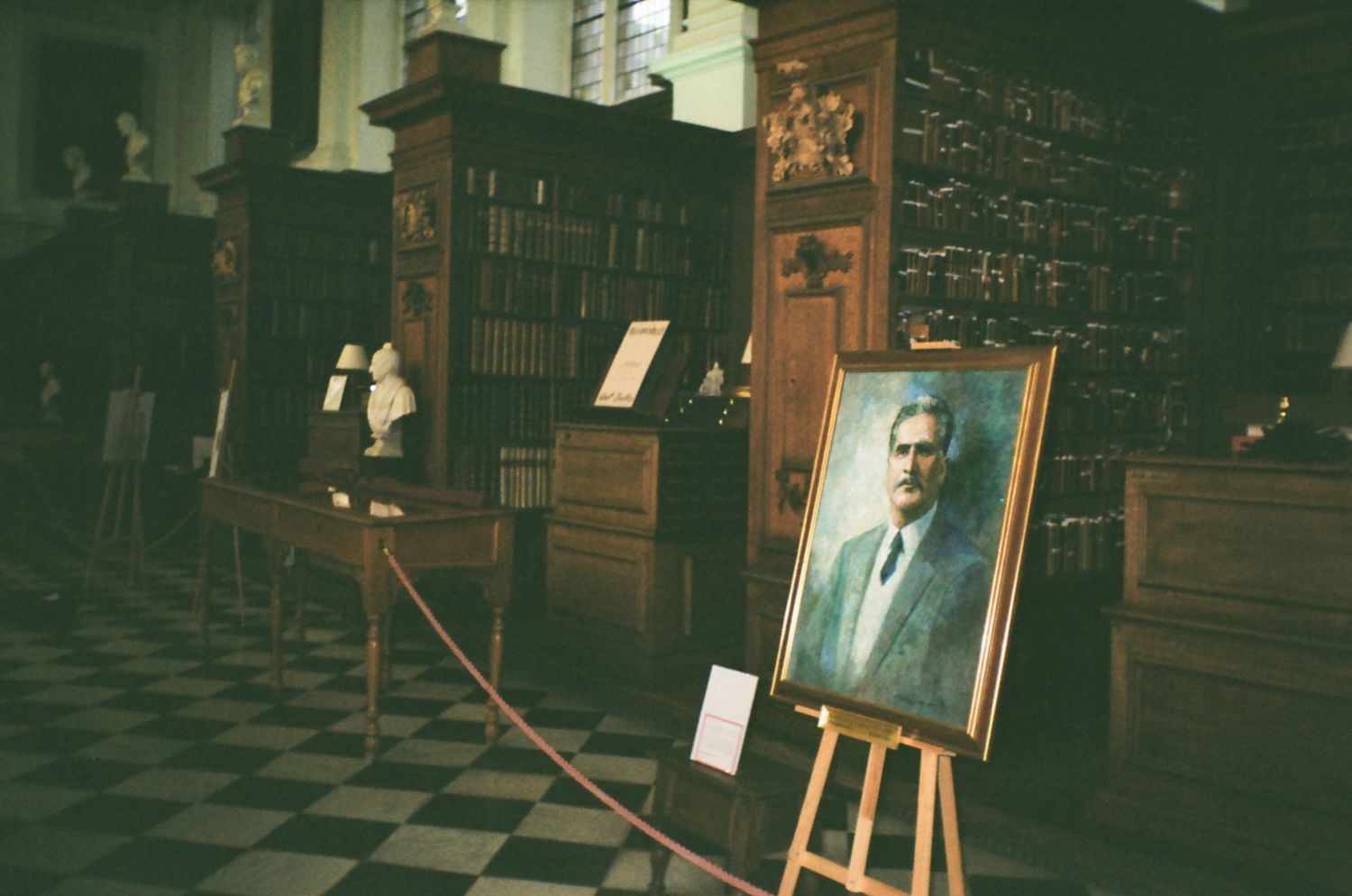

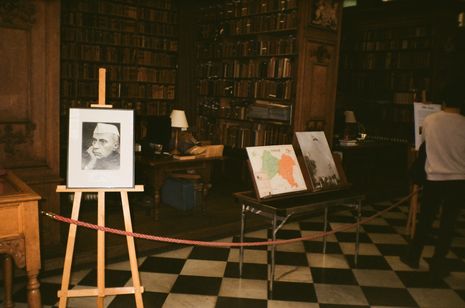

As we retreat from the politics and return to the sentiment, what strikes the eye is that this exhibition is still history-making just as much as it is history-keeping. From the tea-stained Majlis Termcards neatly arranged on the red cushions inside the wooden archive cases that describe the busy affairs of the Society in the early 1900s, to the gold plaque beneath the marvellous portrait honouring the great poet and philosopher Sir Muhammad Iqbal (m. 1905, Trinity, BA) in front of which all the speeches and recitals were given at the opening ceremony, the notions of ceremonial preservation are obvious. There is a red rope that joins together the artwork and archives on ringlets of gold, containing the spectators in a pen of awe and hubbub. I am sure that an arts student could infer some metaphor of blazing revolution here, but more plainly, whether intentional or not, symbols of red and gold for royalty and spiritual matrimony shine bright, a point of unity between the countries of the south Asian subcontinent.

This was epitomised by the recently created bronze bust of the revolutionary Srinivasa Ramanujan FRS (m. 1914, Trinity, Mathematics, the genius behind uncountable recognised mathematical theorems and the subject of the blockbuster film The Man who Knew Infinity): an impression of his passport photo that presides over the gallery in a subtly majestic fashion, reminding us of the service south Asians have continued to make towards Western thinking in the sciences as well as the humanities.

“At last, our community is again truly re-gaining its own status in a place that for so long has defined and confined its identity”

Even as the sun began to set, the exhibition was still blessed with a steady flow of visitors. I left the library clutching my notepad and film camera, like that same ordinary person, on an ordinary day, traversing the plains of Trinity College eager to tell their parents of their adventures. But something stuck with me. Maybe it is the taste of pride and redemption; at last, our community is again truly re-gaining its own status in a place that for so long has defined and confined its identity. This merits, on behalf of all south Asians, the sincerest gratitude to Laleh Bergman Hossain (m. 2020, Clare, AMES), the current president of the Majlis, and her committee, for their thoughtful and incredibly commendable hard work. Scouring the numerous Cambridge libraries and even venturing to the British Library in search of the remnants of the Majlis before its remission in the 70s is no small feat.

And yet, even only as a British-born half-Gujarati, second-generation immigrant of the East-African diaspora, this exhibition has managed to resonate so personally with me. Perhaps because my mother’s brother takes the same name as Uday Shankar, a famed dancer whose performance was enlisted at a Majlis charity fundraising event in support of Chinese Manchuria under Japanese invasion in 1931; more probably because, most strikingly, the publishers of the map on display that depicted divided Punjab post-partition were of the same name as my mother, Dipti.

I therefore cannot fathom the impact, in terms of representation, unity and strength, that there will be for the rest of the blooming south Asian community at Cambridge an exhibition as soul-nourishing and heart-warming as this one, which I believe will surely start a promising and powerful butterfly effect for future generations to come.