This is what is problematic with selective grief

The reaction to Friday’s terrorist attacks proves the West has a long way to go in tackling white prejudice

When bad things happen, our first response is always: “What can we do to help?” Being compelled to act is the ‘human’ thing. We fervently ask ourselves: “How can we show support?” – we’ll give love, money, anything to make things better. There is something of a unified response to tragedy; we temporarily forget our differences and band together to help one another. This is what I saw when my news feed was flooded with tributes, thoughts and kind messages to those suffering in Paris. This is what I saw in the countless people who temporarily changed their Facebook profile pictures in solidarity. Those small gestures were the ways people said: “I’m thinking about victims.” Superficially, it made me want to lean on this idea that this was an inherently ‘human’ reponse.

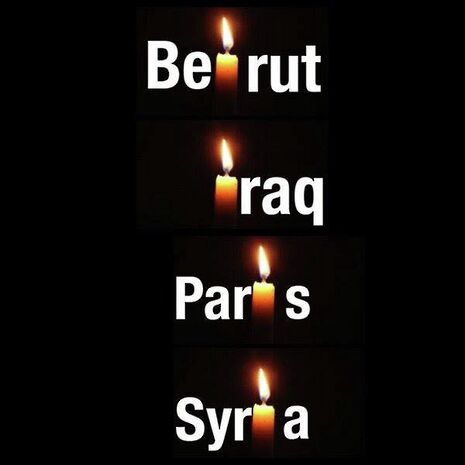

Judith Butler puts it well when she says: “The question that preoccupies me in the light of recent global violence is, who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? And, finally, what makes for a grievable life?” What struck me about the response to the attacks was how willing people were to share their condolences, their thoughts, anger and messages of hope for people who looked like them. The response taught me that in the face of global violence, lives are not viewed in the same way. If we consider the amount of news coverage given to this event versus attacks that happened in Lebanon just a day before, we are confronted with the idea that it is easier to ‘grieve’ for Westerners because their lives are maintained by a power structure that makes them real to us. They are nuanced multifaceted human beings with families and histories. Non-white, non-Western bodies are just collateral damage. I have no doubts that if many people investigated why they were deeply saddened by the Paris attacks and not by the constant, never-ending deaths of non-white bodies on a daily basis, the ultimate response would be: “Well it is easier to express sorrow for someone who looks like me.” It is this kind of selective and performative grief that meant that I couldn’t properly engage with social media after the attacks because more than a show of solidarity, every change of a profile picture, every tweet, every controversial status felt like a constant reminder that in the face of horrible events, we forget to think critically. When we forget to think critically, we reaffirm the idea that some lives are more important than others.

It is possible to express sorrow and condolences while also remembering that France is one of the largest exporters of Islamophobic propaganda and violence that is fuelled purposefully by attacks like this. I had friends whose first reactions were to check that their visibly Muslim friends and family in France were safe, because when Hollande states that France’s response will be “ruthless”, it is clear that he is not thinking about the non-white bodies that will be discarded in his country’s retaliation in the same way he is thinking about white French victims. I see this same idea echoed in the strange demands for Muslims to “condemn” the attacks. I want to be very clear about this; Muslims around the world owe us nothing. Not their apologies, not the signs that they will hold up to tell us these attacks were ‘not in their name.’ It is truly a sign that we treat Muslim people as a homogenous mass and disallow them agency when we ask them to comment on attacks that are as alien to them as to non-Muslims. If we are working on that basis, the West should ‘apologise’ from now to the end of time. I wonder what it must be like to switch on the television and have your community scorned, homogenised, to be constantly subjected to violent generalisations. Our insistence on finding someone to blame reveals the ugliness in our responses to grief. It demonstrates that ‘shared humanness’ is false because the second the West becomes the victim of violence, it repels non-white bodies and sends them into exile. They are forced to apologise, to console and with every demand we make of them in the face of terror, we rob them of their humanity and their possibility for a nuanced response.

It hurts to think that people we share space with, friends who we like and admire, unknowingly value Western bodies more than those in the global South. It is sad that they will take their grief as a given and never fully investigate why they can cry for Paris but not for Beirut, or what it means to turn grief into a spectacle. Everywhere is in chaos, but the bubble that we exist in, one that is exaggerated even more by how insular Cambridge is, only ever bursts when white bodies become the victims of violence. It is then that we raise our heads, that the Senior Tutors send around emails, that we observe minutes of silence because we have learnt how to grieve for white people. We have yet to understand what it means to look outside of the West, outside of whiteness and extend that same compassion to the global South. Until we do, the same cycle continues – terror, grief, solidarity. Somehow non-white students find themselves constantly on the outside looking in.

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 News / Cambridge University cancer hospital opposed by environmental agency12 April 2024

News / Cambridge University cancer hospital opposed by environmental agency12 April 2024 Interviews / In conversation with Dorothy Byrne1 March 2024

Interviews / In conversation with Dorothy Byrne1 March 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024