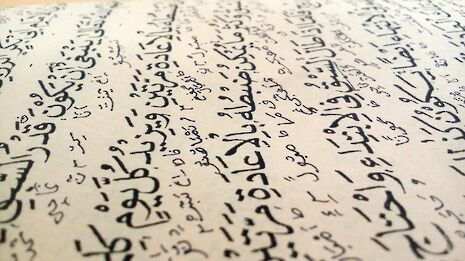

What an Arabic degree teaches me

Learning a language is not only the acquisition of a skill but a lesson about the world we live in, and a way of looking beyond Western perspectives

Whenever people ask me why I chose to study Arabic at Cambridge, I always say that it’s an easy way of getting into university. I’m not sure why I start with that, instead of listing all the valid reasons behind my decision. I tend to leave all the things I love about the course, and the factors that motivated me to pursue an extremely difficult language at university-level having never studied it before, to the end.

Language study has exposed me to new ways of thinking, and given me the opportunity to engage with new groups of people that I previously would have only had superficial conversations with in my mother tongue and not theirs.

The nuances of each language become clearer the more you learn, and although the ability to discern conversational modalities in another language is not easy, I believe that it is a worthwhile challenge. The international dominance of the English language often means that native speakers rarely have to step out of their comfort zones to express themselves: something I have found tricky when conversing in another language. To constantly navigate conversational expectations is really difficult, and native English speakers should have to experience this. This skill can be gained by studying a foreign language at university.

I’m so grateful that it was from the perspective of an Egyptian scholar rather than a white European historian

However, on the whole, people aren’t interested in studying languages, let alone a language which is primarily spoken outside Europe. Waning interest in modern foreign languages could explain the lack of diverse sources and subject matters that are presented to us. Because less people are interested in Arabic, it means that its scope has been shaped by a certain, select group. Unfortunately, and unarguably, this has historically been the case.

I studied History all through primary and secondary school and never tired of it despite learning about 20th century warfare, political upheaval and economic turmoil from the same Western outlook at three different schools. I found it incredible that regional developments in the Middle East were either disregarded, only viewed as anecdotal, or examined from outdated British perspectives. How could something that was at the centre of international headlines throughout my teenage years be at the periphery of my schooling?

Since coming to university I’ve been exposed to a greater range of historical sources. In my first year, our introductory source text was about the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, and I’m so grateful that it was from the perspective of an Egyptian scholar rather than a white European historian. This wasn’t a one-off nor was it tokenistic, but set a precedent for providing an abundance of perspectives. Is it too much to ask for balanced collection of sources? One that provides students with an adequate and accurate scope of history and forges the necessary tools for critical thinking.

Studying Arabic as part of a regional Middle Eastern studies course has allowed me to maintain the interests I had in high school: history, literature and language, while also exposing me to other areas such as anthropology and linguistics. I appreciated the way in which different papers were introduced to me in first year, thus allowing me to decide what to specialize in for the following year.

The Year Abroad is another unique feature of language degrees, and although the opportunity to study abroad has opened up to other subjects, I find those which are anchored in language study particularly special. I value the way historiography is scrutinized and questioned, even when we’re not strictly studying history. Whether I am studying anthropology or literature, the very mechanisms that have taught us are addressed and unpacked.

To learn about the Middle East without an awareness of the context in which we are able to do so is embarrassing. Although European interest in and study of the Middle East has been dominated by white men, I think that the course here has struck the appropriate balance between a variety of sources. Moreover, the historical reality of British scholarship in the region is addressed, and accounts by those writing during the time of Empire are not glorified. However, acknowledgement of Britain’s bloody past should not be a rarity, only challenged when it fits neatly into a specific narrative. Its inclusion should not only rest on whether or not it is vaguely relevant but should be expected no matter the context. To disregard it would be historically inaccurate, and an injustice to all those who suffered under it.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024