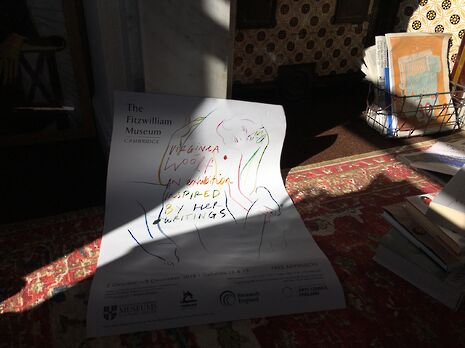

Virginia Woolf: An exhibition inspired by her writings review

Vivienne Hopley-Jones reviews the Fitzwilliam Museum’s latest exhibition which places the writer Virginia Woolf in a complex web of female artists

Wandering around the large, familiar rooms of the Fitzwilliam museum, the building breathes with a new lease of life following the opening of it's latest exhibition. Curated by Laura Smith, the environment of ‘Virginia Woolf: An exhibition inspired by her writings’ is vivacious and inspiring. Sprawled on the floor in a corner, a young woman sketches in a dark notebook. It takes me a moment to register that the group of women sat on stools, fervently drawing, are not part of the exhibition also. Two other visitors stand together, whispering and staring intently at the silk canvas upon which artist Emma Talbot has scrawled “Paintings by OLD MEN covered the WALLS. They lurked By their WORK in THICK KNIT jumpers”. I can’t think of any words more pertinent to highlight the distance this exhibition achieves from the standard experience of gallery-goers.

Woolf is used as a point of access to the vast world of female art within which she is situated

Your head is left swimming in a vast pool of female creativity and talent – swimming because, despite going to the exhibition with a view to celebrate the life of an inspirational woman, you are left realising just how many female artists you remain completely oblivious to. Having studied art before university, I am reminded of the limits of the education I received. Unprepared to be reminded that everything I had been taught had been filtered through a pervasive male lens. This is hardly news, but Smith’s exhibition tears at remaining misconceptions about the historical contributions of women to the arts. Art produced by women exists within a singular contextual history that runs parallel to the dominant mainstream world of ‘male’ art.

If you are looking for a historical walk-through of the life of Virginia Woolf, prepare for disappointment. Smith chose to structure the exhibition thematically instead of a more predictable chronological ordering. Rooms encase themes spanning from the ‘the self in private’ and ‘still life, the home and a room of one’s own’. The towering white walls become canvases, across which the female form dances and sprawls. The lines of the human bodies guide you through the otherwise blank walls of the gallery, tracing a history of female artists which the content of the exhibition also follows.

Debates about our feelings of right to space are as lively today as they were at the time of Woolf’s writing

The collection is about much more than the author’s life story that is so often the focus of retrospective collections on Woolf. Instead, she becomes one within a rich legacy of female artists. Exhibitions celebrating female artists often focus on the successful female artist as ‘the exception’ – as a rare case of a woman who managed to break through the mould of masculine dominance in the arts. Here, Woolf is used as a point of access to the vast world of female art within which she is situated.

The artwork ranges from paintings of the writer in the author's own home crafted by her sister Vanessa Bell, to more modern works such as Penny Slinger’s ‘Read My Lips’ or Hannah Wilke’s sculpture ‘Sweet Sixteen’. Vast swathes of the display play on female form. Surrealist paintings sit alongside Wilke’s sculptural representations of vulvas. Collages follow on from photo-realism and Bell's acrylic portraits or ceramics. The artists and styles featured span the globe and history.

With no clear linear narrative, the diffusive influence of Woolf can be grasped. Her memory is surrounded by the art that inspired her, the art that was influenced by her, and the art that bears no explicit link but is situated in this continuum of female creativity. It becomes an exploration of the collaborative nature of inspiration in art in a refreshing and raw way. It forces reflection on the artistic and literary scenes within and outside of Cambridge today beyond the new sculpture at Newnham.

Her memory is surrounded by the art that inspired her, the art that was influenced by her, and the art that bears no explicit link but is situated in this continuum of female creativity

Smith’s structuring of the exhibition allows viewers to reflect on their own place in this history of womanhood. For me, ideas about space took the forefront. Woolf’s seminal essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ was never far from my mind, especially with the exhibition centring on the original manuscript of the text which was bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam following Woolf’s death. Debates about our feelings of right to space are as lively today as they were at the time of Woolf’s writing of the speech she gave to students of Newnham college. Feeling ‘at home’ in two cities as a student, navigating spaces within and outside my University I sometimes fear I don’t deserve access to, trying to carve out an identity in a world that feels unstable and confusing; Woolf’s own words still spoke to me through the exhibition. The exhibition allows you to take what you need from it.

The comment of the friend with whom I visited the exhibition returns to me: what is beautiful about the collection is that it refuses to place Woolf in isolation. Similarly, as viewers we don’t feel isolated. We are placed within a web of experience, life and womanhood. Woolf may have been calling for a room of ‘her own’, but Smith succeeds in expressing a sense of unity that under rides the work of all of these artists.

“One only has to go into any room in any street for the whole of that extremely complex force of femininity to fly in one’s face”. These words plastered on the walls of Fitzwilliam Museum speak to the experience of visiting the exhibition. The complexity of a deep history of womanhood, femininity and female artists flies in your face. You aren’t left with anger, simply wider eyes.

Virginia Woolf: An exhibition inspired by her writings runs at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge until 9 December 2018

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024