Unravelling mysteries at a Milanese auction house

Alessandro M. Rubin reflects on his summer at a contemporary auction house evaluating real and counterfeit artworks

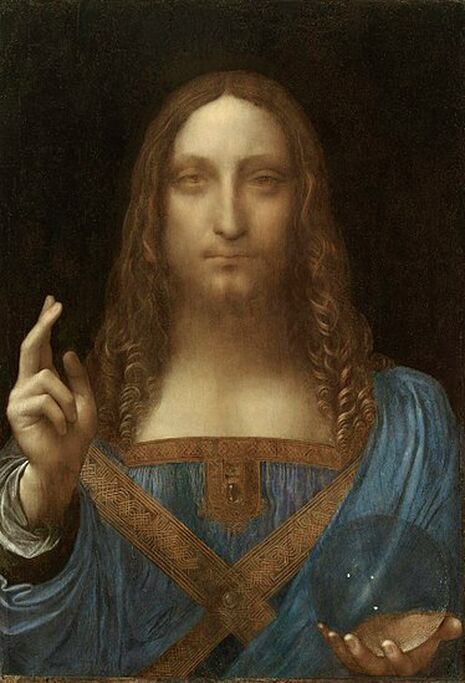

At the end of June, I joined the team of Art-Rite, an auction house based in Milan specialising in modern and contemporary art. For many art-history students like me, the auction business is a desired destination, since it stands at the intersection between the art world and the luxury industry. Auction houses operate on the secondary market, facilitating the exchange of works of art which have already been sold in the past. Auctions are often accompanied by an aura of grandeur, partly thanks to the outstanding prices recently generated by works such as Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi, sold for about $450 million at Christie’s in 2017. I wanted to recount my experience of this vast and complex universe.

Milan is a key location within the art world, thanks to the thriving fashion, luxury, and design industries. The office where I worked, located in the district of Lambrate, is surrounded by galleries and designer studios, providing a prolific creative environment. The interior resembles that of any other office, with desks, computers, shelves, and so on. However, works of art would occupy the entire space, displayed on the walls, piled here and there, or sitting on a table waiting to be studied. The first impression was both surreal and profoundly exciting, as the works did not feel ethereal and distant, as sometimes happens in the museum context, but close and candid, open to my gaze.

At Art-Rite, my job consisted of assisting the specialist department, that is to say, the group of professionals selecting and evaluating the works to be sold. On a daily basis, customers would contact us for valuations. We would consider whether their objects were genuine, establish an esteem, and hopefully insert them in the catalogue of a coming sale. Inevitably, every work has a different story and needs to be treated individually. One day, I would examine a new work of art looking for traces of authenticity, contacting the artist’s estate or comparing it to other known pieces; another day, I would check past auction results to see the pricing trends for a given artist; closer to the auction date (sales usually stop during summer), I would be writing essays and critical texts for the catalogue.

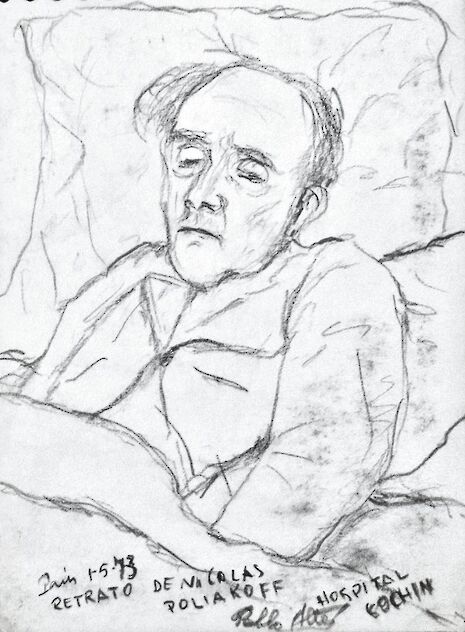

When I was first asked to analyse a drawing on paper by Nicolas Poliakoff, a French painter, I struggled with the idea of picking it up with my own hands

My first somewhat shocking realisation was that works of art are tangible objects. It may seem banal but when I was first asked to analyse a drawing on paper by Nicolas Poliakoff, a French painter, I struggled with the idea of picking it up with my own hands. This is necessary since you need to check the conditions of the work, look for labels from previous owners, and so on. Yet, it felt weirdly invasive, I believe because of the idol-like connotation that art has acquired in our imagination thanks to museums. This hides part of the artwork’s material beauty; especially in sculpture, for instance, being able to feel the texture of a surface can make a huge difference in terms of how we perceive a given work.

During my internship, I found out that investigating a work’s history is like solving a mystery. I remember once being presented with a print, supposedly by Francis Bacon. However, I immediately noticed that the signature did not exactly correspond to the artist’s. Moreover, it was a rather large one, located in a corner of the sheet. Similarly, the date was quite big too. Then, I noticed some incised lines beneath the written portions. It looked like somebody had erased a pre-existing pencil text leaving a group of white grooves cutting through the paper. To decipher them, I took a sheet of paper, laying it over the written area; then, using a pencil, I started covering gently the sheet to reveal the signs below. What I found were the original signature, by a different artist than Bacon, a date later than the written one, and the text “homage to Francis Bacon” written in Italian. While it is impossible to reconstruct the full history of the piece, it seems likely that one of its previous owners deleted the original signature, trying to disguise the work as an original Bacon. As a consequence, we were forced to return the object to its owner.

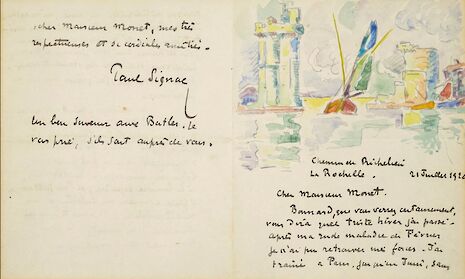

The Bacon’s case shows how important contact with the works of art is. While a work of art is usually associated to a specific date of creation, successive interventions can alter it and add further layers of complexity. This is the case, for instance, of a peculiar art form that I treated during my internship: mail art. It consists of the circulation by mail of small-format works between artists, critics, and collectors. Postcards, drawings, and collages are all potential mail-art material. However, the value of these objects is not limited to their material dimension but extends to the network of relations that they establish by passing from one owner to another in a form of relational aesthetics. In this regard, the value itself (even in terms of price estimates) depends both on the artist and the various owners of the work.

Often, visiting museums and galleries gives us a partial view of the art world. In a way, we are fed a certain narrative which does not fully correspond to the dynamics of this industry. By working in the art market, I was able to see further levels of complexity, each of them tightly tied to the individual stories and vicissitudes of the works of art and their owners, both past and present.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024