‘You should be working’: finding time for creativity in exam term

As stress relief becomes stress-inducing, Esme Garlake argues that we should maintain a creative output that is free from academic constraints

We tend to see happiness as the opposite state to stress. As exam term approaches, there are probably very few people who are expecting to spend it in a consistent state of contentment and satisfaction. Without wanting to be too cynical, I would suppose most of us are readying ourselves for what can be a hugely stressful period. Of course there will also be moments of enjoyment, in between solidifying committed relationships with libraries and our bedroom walls. Personally, my holidays tend to revolve far more around mentally bracing myself for Cambridge lock-down. In other words, making the most of freedom while I can.

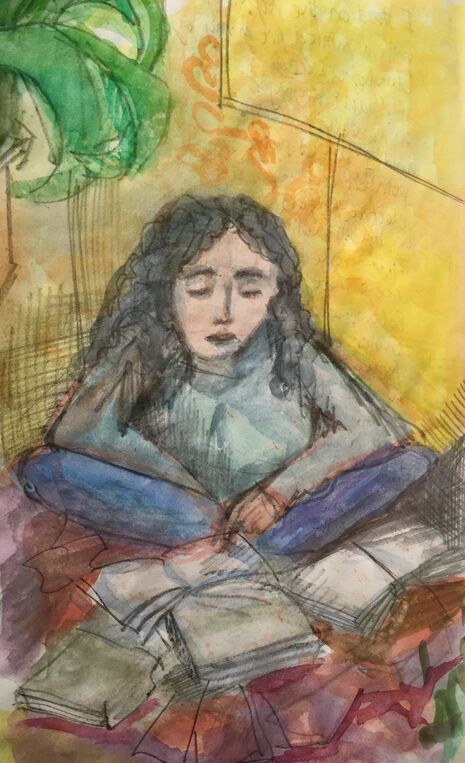

For me this freedom is synonymous with being creative. During the holidays, it feels like a luxury to have the mental space to do some art or write poetry. I am (just about) rid of that quiet but ever-present voice whispering ‘you should be working’. Next term’s exams will certainly intensify Cambridge’s ability to make anything other than work seem like procrastination. But, when we’re in the full swing of revision, taking this approach only seems to dim the light at the end of the tunnel.

“My holidays tend to revolve far more around mentally bracing myself for Cambridge lock-down.”

It is inevitably hard to let yourself take time to be creative when it is drilled into us that to do this is a form of divergence from our ‘real’ work – the workload alone sets this expectation. The search for ‘permission’ is made even harder considering that creative activities are generally more solitary and informal than societies or sports. Perhaps for this reason exam term is a good time to check out more social creative pursuits, such as life-drawing or open mic nights.

Obviously stress comes in many different forms and intensities, and unhealthy habits and thought-processes can re-emerge with new force in times of tension and strain. But if you do allow yourself to indulge in a few minutes spent crouched over a sketchbook, or scrawling frustrated poetry alongside revision notes, it might be that you find the release that makes it possible to keep some perspective and process your frustrations. I find that stress has sometimes helped me to be much more creative, as if the only emotional outlet is through reflecting my worries through being creative.

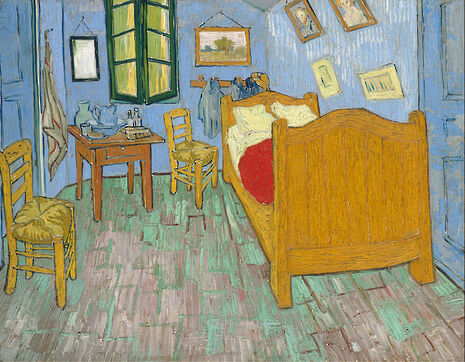

Indeed, perhaps some of the best art has come from difficult circumstances. It isn’t hard to think of famous artists and writers who suffered significantly during their lives: Oscar Wilde, Vincent Van Gogh, and Frida Kahlo, to name a few, although clearly their pain was more extreme than the stress of university exams. Some might say that Amy Winehouse’s music depended on her wrought personal life, and vice versa. Surely the tragedy of her death, however, woke people up to the injustices and struggles that are excused by the myth of the tortured artist.

“Stress is constantly justified as a prerequisite for creativity, academic or otherwise”

Yet this glorification of the painful circumstances of others remains prevalent. Arguably this myth can even be seen on a micro-level in Cambridge, where stress (not just a few extra library hours, but eating disorders, depression, anxiety, drug abuse) is constantly justified as a prerequisite for creativity, academic or otherwise. The expectation that everyone must transform their pain into something ‘worthy’ not only promotes a destructive struggle between suffering and creativity. It also means that when the difficult situation transcends our ability to respond to it creatively, we are left feeling even more at a loss. At my most overwhelmed, it feels impossible to grasp anything other than the fact that I am, to put it simply, not happy. A blank page does not offer comfort, but rather stares back at me as if a reminder that I have ‘forgotten’ how to be creative. When stress stops us from being able to do what comes most naturally to us, it only exacerbates the situation: you start to fear that you have become your stress, and lost yourself.

I find that academic stress in particular pushes out any artistic ideas. The need to process and retain so much information for exams seems to make it impossible to produce anything beyond work, even if it might have been the best stress relief at another point in time. It might come down to the mentality of exam criteria and marks that can start to transfer over to creative work, a part of our lives that should be free of assessments. Our constant quest to predict other people’s judgments and act accordingly is already entrenched enough in our day to day lives: we only need consider how strongly our online self-presentation is determined by others. The pressure of exams, which is entirely based around performing well according to another’s view, only adds to this dynamic.

“Being creative does not need to play to the examiner’s shadow”

For, once the self-checking starts to take over, every piece of art seems to emerge according to an examiner’s eyes. The stress-reliever becomes stress-inducing. I find that when I am stressed, I doubt myself far more acutely, and I raise my expectations far higher than I would if I was relaxed and able to shake off an artistic ‘failure’ far more lightly. Perhaps this is why adult colouring books have become so popular: they offer (relatively) creative distraction without the pressure of creating something entirely from scratch.

Although Exam Term might seem to render creative pursuits practically impossible, it does seem a shame to reserve creativity solely for life outside of Cambridge. Perhaps if we try to see it as a justified equivalent to other forms of stress-relief, like an evening of Netflix binges or excessive biscuit consumption, we can use it as a tool to help alleviate both academic and creative pressure, and we can learn to be creative without an audience. Unlike in exams, being creative does not need to play to the examiner’s shadow. Drawings can be made without wondering how they will look online, and writing can evolve without thinking about where it will be published. Scribbling poetry across a page or doodling the person sat in the corner of the café should have no outcome other than holding onto a little bit of our creative selves. Even small acts like this can provide a quiet message of defiance within ourselves, as a reminder that the stress of Cambridge does not have to totally overwhelm who we are.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024