Practical Shitticism: Valentine’s Day card badges

Lily Lindon critically analyses the badges found on Valentine’s Day cards as an exemplar of modern romance

This week I would love to discuss the medium of badges found on Valentine’s Day cards. Some may argue that this is a somewhat ‘overworn’ academic topic. I fundamentally refuse to apologise for being an ardent badger.

Valentine’s cards with a badge have long been sought after as they are the only known evidence that someone truly loves you. And no wonder, for these badges contain some of the most beautiful, poignant, and frankly arousing poems known to humanity. Perhaps this is because the limited amount of space on the shiny round ‘page’ draws attention to the complexity of the few words emblazoned thereon. Or perhaps the appeal is most manifest in the satisfying bulge which protrudes underneath the card’s envelope when you gently stroke it.

“It is a tactile, sensory way of engaging with words, and an incredibly postmodern way of performing the ‘Valentine’ identity”

Yet one cannot say that badges are just about words. No, no. Few can think of something more romantic than publically claiming ownership over your Valentine with a glittery pink badge-ring. In the words of famous love artist Beyoncé, if you like it you should put a badge on it.

Furthermore, the materiality of the badge form invites the reader to consider poetry like clothing, and importantly, accessories which are like poetry: it is a tactile, sensory way of engaging with words, and an incredibly postmodern way of performing the ‘Valentine’ identity. It goes without saying that badges are also a beautiful embodiment of the ‘pain of love’: Cupid’s arrow is behind every one, as by fastening the badge to your chest you will feel a tiny stab of love right into your heart... Of course this also suggests that your Valentine is a little prick.

As is traditional on Valentine’s Day, let’s analyse some 21st-century badge poems to consider the true meaning of love.

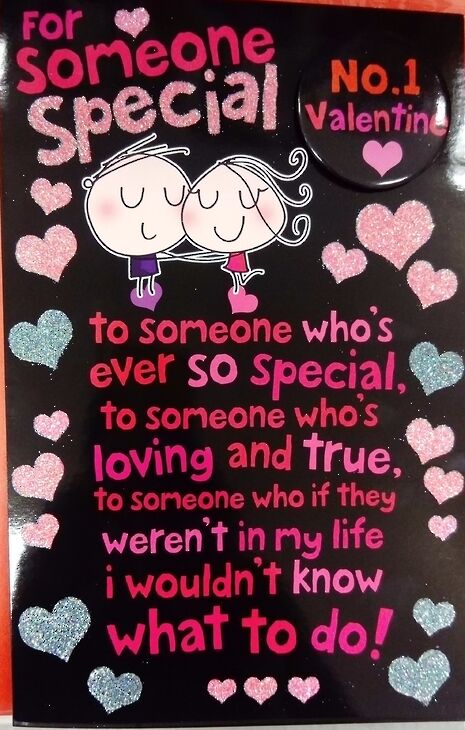

Where can you begin with this riddle of poem? Perhaps with the number one. The use of an arithmetical value here has complex implications. The reader does not know whether being ranked as the #1 integer means that they are currently the winning Valentine, or merely the first Valentine on the extensive badge-receiving list. Usefully, the badge can also be used to pin to yourself if you are single: you have ‘No.1 Valentine’, but are ready to meet a special someone.

Confusingly, this could also be interpreted as a display of your asexuality or, indeed, polyamory. Therefore, this badge displays a complex and ambiguous wordplay which contains within it all the contradictions, flexibilities, and possibilities of modern love. Or perhaps there are simply multiple people called Valentine in a friendship group and this has lead to the need for having differently numbered Valentine badges – it’s most likely this.

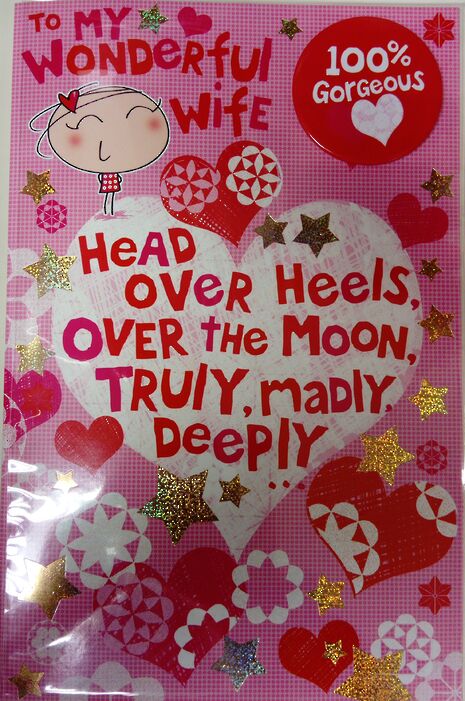

There is a very similar use of numbers on this next poem. ‘100% GorGeous’ is written in bold white typography on a red badge, next to a card addressed ‘TO MY WONDERFUL WIFE’. This badge is clearly a feminist satire of sexism. The wife is supposedly both ‘100% GorGeous’ and ‘wonderful’: a mathematical impossibility. Clearly the parody suggests that an attractive woman would not have the intellectual capability to understand that insult. It would seem that there is no room left in the woman’s GorGeous body for her to have personality, career aspirations, or, say, a dislike of bonsai trees. Instead, she is forced to literally wear the impossibly high standards which the media sets for women to be physically ‘perfect’.

That the badge contains the symbol of a heart is incredibly ironic, given that the message written above it does not care at all about her feelings, or her un-gorgeous organs. Fortunately the excessively pink card adorned with hearts, glittery stars, and a figure wearing a dress, means that the overall tone is self-aware and not in any way clichéd or stereotypical. The fact that the font on the badge uses seemingly random capitalisation furthers this sense of radical literary experimentation. (It’s also, of course, a Marxist social commentary pointing to the failures of the capitalist system.)

This one just means that your Valentine was completely in love with their ex but didn’t have room for another ‘e’. If someone wants you to wear this in public it means you’re even worse than that twat was.

In conclusion, if you are considering purchasing or wearing a poetical badge this Valentine’s Day, do remember to do your literary analysis beforehand. I recommend starting with the AQA A Level exam reading list for the module ‘Love Through the Ages’. If that doesn’t arouse your love for words and get your badge-poetry muse begging for more, I don’t know what will.

100% youRs,

Lily x